Missing Pieces and Missing Pages: More On “Twin Peaks”

Much of the Twin Peaks universe deals in liminal spaces, despite the stark contrast of that black and white tiled flooring.

Read More

Much of the Twin Peaks universe deals in liminal spaces, despite the stark contrast of that black and white tiled flooring.

Read More

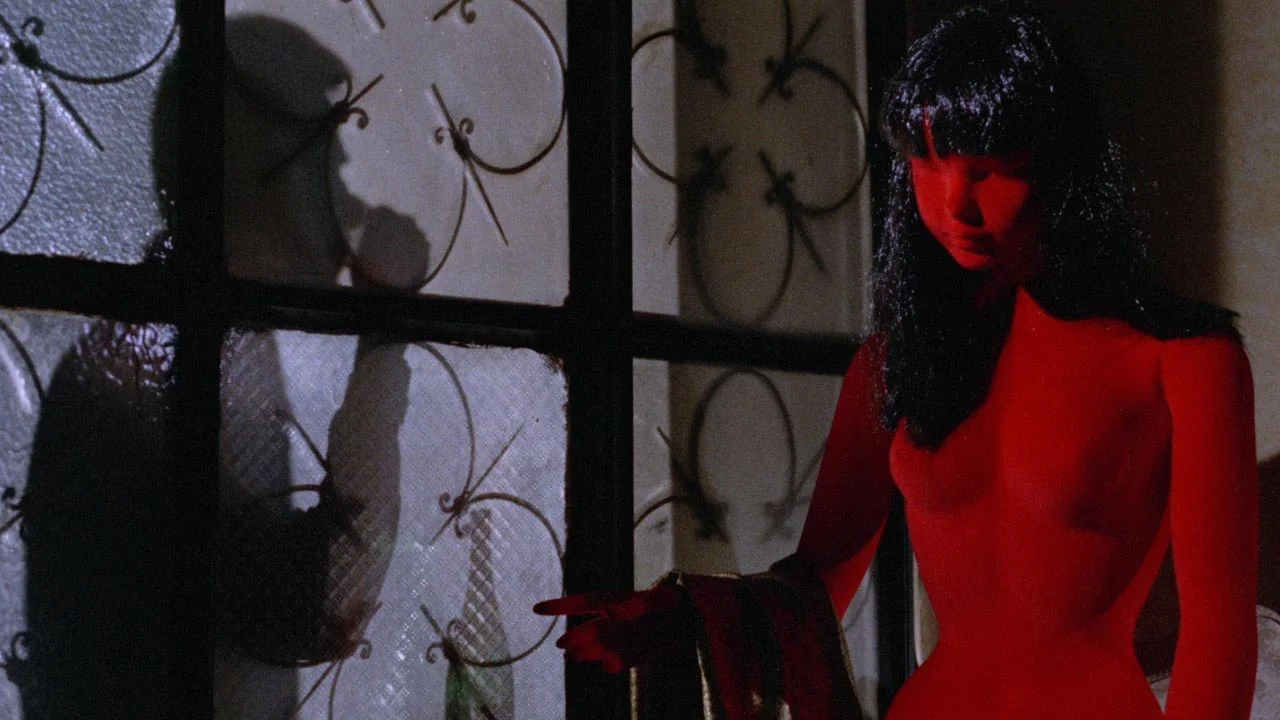

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me shows us portals between dreams and reality, but does not provide us with conclusive answers.

Read More

Mario Bava's 1964 film Blood and Black Lace sets the tone for the Gialli of the 1970s and beyond.

Read More

The Neon Demon, on the surface, seems to be about a lot of things, but it portrays a world of very real horror.

Read More

When it comes to Man vs. Beast movies, sometimes it's best to leave well enough alone.

Read More

Mark Duplass's Creep brings the found footage horror film to the next level.

Read More

At some point in the 1990s, before became a horror junkie, I worked up the courage to watch 1978’s Magic. You know, the one where Anthony Hopkins portrays Corky Withers, a ventriloquist for the dummy known as “Fats,” who may or may not have a personality of his own.

That premise is creepy enough: my lifelong dread of ventriloquist dummies (or what Neal on Freaks & Geeks called “figures”) was set in stone thanks to the Howdy Doody that lived at my grandma’s house. The scariest scene in Magic takes place after (SPOILER ALERT!) Corky/Fats kills his agent Ben Greene (Burgess Meredith) and drags the body out into a nearby lake. Greene, however, isn't dead and his unexpected gasps for breath terrified me far more than any of Fats’ shenanigans. The experience was akin to falling into a deep, black hole; it was almost like the utter terror of a panic attack but concentrated into a few seconds. There was nothing else; only the feeling that I was actually going to die of fright.

The idea of dying of fright wasn’t new to me. As a kid, I was a big fan of the William Castle-produced The Tingler, starring Vincent Price. Price portrays Dr. Warren Chapin, who becomes fascinated by Martha, the hearing-impaired wife of a movie-theater owner named Oliver Higgins. Similar to the spirit of death in The Asphyx, “The Tingler” is a parasite that resides within every person. When that person is afraid, the Tingler grows stronger. If that person cannot release that fear, it is possible, Dr. Chapin believes, for that person to literally die of fright when the Tingler crushes their spine.

I was mildly obsessed with the idea not that the Tingler was real, but that a person could actually die of fright. Was this part of the reason I avoided horror films for so long? Or did I subconsciously know that I would eventually become somewhat addicted to them?

Surprisingly, for someone who claimed to be too scared to watch horror movies, I sure did watch a lot of them. And oddly, many of them were simply not scary. It seemed that it was the fear of fear that kept me away. There were major exceptions: Fulci’s The Gates Of Hell, Zelda in Pet Sematary, that part in Jeepers Creepers when the creature realizes Trish and Darry are watching him, when the alien is shown on the roof of the house in Signs. After I learned to relish the feeling of falling into a hole, I began to crave it.

Yet each time that feeling would eventually subside. I became convinced that the filmmakers knew that they had to ease up on the fear factor or it would be too much for viewers to handle, as if there was some precise algorithm to determine how much fear an audience would experience, when they would experience it, and the best ways to hold back to avoid killing them.

The more I craved That Feeling, the more movies I watched in an attempt to evoke it, and eventually it became harder to feel that specific type of fear. Of course, I felt scared watching horror movies, but that specific “falling off a cliff into a dark, bottomless pit of fear” feeling was rare. When I experienced it (like the first time I saw The Descent, for example) I was so terrified I just started crying. I was preventing my own Tingler from killing me by releasing my emotions in a strange and unexpected way.

The most profound example of this was the first time I saw À l’intérieur. I was home by myself, yes, but it was on a sunny afternoon. This film, with scant few jump scares but a veritable ocean of blood made me so scared that I started crying about a half hour in. When I finally stopped, I started thinking that maybe that magic algorithm had been utilized. Yet, the film wasn’t done with me, because it all started up again just a few minutes later, leaving me a literal, sobbing mess long after the credits had ended.

Ladies and gentlemen, I had broken my own fear barrier.

Once that happened, I felt like I could watch anything, thinking I’d probably never get that feeling again. Which is why when it has happened a few times over the next few years (Insidious, “Second Honeymoon” in V/H/S, Session 9), it has been a huge surprise. I still seek out that feeling because despite those few seconds of panic, it is one of the most disturbingly satisfying sensations in the world.

If you’ve seen films like The Road or We Need to Talk about Kevin or the more recent Nothing Bad Can Happen, you likely know that there is bleak and then there is black-hole bleak, films that are so dark they make you lose faith in humanity. When bleak films have classic horror elements such as supernatural entities, classifying them as “horror” is easy enough. What happens, however, when they are firmly set in reality?

1986’s Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is considered a “psychological horror film” by Wikipedia. Tony, directed by Gerard Johnson in 2009, is described as “British social realist comedy/drama” on Wikipedia. It’s also based on a serial killer, one Dennis Nilsen. Although there are definitely comic elements, it’s a nasty bit of work, one with enough gore and grime to make you feel like you need ten hot showers.

So where do we draw the line? Is realistic horror somehow less horrific than vampires, zombies, or masked serial killers who can’t be killed? That scene in The Road where Viggo Mortensen’s character discovers the people in the basement is burned forever into my brain as a genuinely horrifying moment. Most of the time I spent watching We Need to Talk about Kevin my stomach was in knots because I knew something terrible was going to happen and that no one would believe Eva when she tried to warn people about Kevin.

Nothing Bad Can Happen consists of a series of increasingly awful scenarios set into motion by Benno (an adult) to torment Tore (a teenager). If you’ve seen that film, you’ll remember the cat scene, the garbage scene, or the scene in the trailers. How are the egregious acts depicted NOT horror?

These kinds of movies often get tossed into the “genre” category which is a polite way of saying “we know this movie is scary but we don’t know what the hell to do with it.” Not that movies like the ones I’ve mentioned need to be categorized to be good (or effective), but imagine how difficult it is to market these or get them distributed.

That’s the real problem. These are the kinds of movies that tend to be ignored, vilified, or forgotten altogether. Although We Need to Talk about Kevin snagged a BAFTA for Tilda Swinton, The Road received only limited release and its box office returns were only slightly higher than its budget. Nothing Bad Can Happen received both boos and cheers at its Cannes premiere, and to date has earned a paltry $4K worldwide from its purported half-million budget.

No matter the budgetary limitations, these kinds of frightening, unclassifiable films will continue to be made, but in a cinematic landscape dominated by blockbuster franchises, it’s become increasingly difficult to get them financed. By opening up the horror landscape to more varied fare, from both critical and audience perspectives, we can, however, ensure that that they don’t get lost in the shuffle and that those who want to make them are able to do just that.

Count Dracula, 1977

When I was younger, lots of things terrified me. Not all of those things were intended to be scary, either. It's one of those burdens that some kids are just forced to bear.

One of my earliest fears was of vampires, inspired by a BBC TV production of Bram Stoker's Dracula starring Louis Jourdan. That two-part miniseries forced me to sleep with a crucifix, a rosary, AND a Bible for at least two nights. A few years later, the trailer for Halloween III terrified me to the point that I had to change the channel when it came on. Horror movies haunted me for years and were responsible for many sleepless nights and panic attacks.

At one point, it was the clown puppet in Poltergeist, then Pazuzu in The Exorcist. An unexpected screening of The Gates Of Hell at a friend's house when I was 15 was particularly scarring. When I was in my twenties, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was so terrifying that I couldn't get through it the first time around and had to wait a couple of decades to work up the courage again. 28 Days Later, Signs, Jeepers Creepers, The Descent, À l'intérieur, Insidious... all of these thrust me into varying levels of fright, from heart palpitations to openly weeping from fear.

Most recently, it was the movie February that got under my skin. Even though I saw it during TIFF in the daytime, it stayed with me in the way that all effective horror films do: you think of them in the middle of the night when you wake up to get a drink of water and get the actual creeps.

Being completely and thoroughly scared throughout an entire movie is rare. This isn't just an empirical perspective; good horror filmmakers know how to layer jump scares, creeping dread, and/or gut-churning gore in ways that are calculated to shock the senses at key points. Yet, as every hardcore horror film fan will admit, it becomes harder and harder to find movies that will completely scare the hell out of you. Part of this is due to becoming older and wiser; part of it is due to desensitization.

For many, the pop cultural glut of zombies has rendered them not only not scary, but annoying. In the last decade alone, we've seen countless movies and at least five different TV series about zombies, one of which is Fear The Walking Dead, a spin-off of The Walking Dead, a show whose ratings have increased every year since 2010. Zombies, it would seem, are everywhere. So are they still scary?

One of the most frequent complaints about The Walking Dead (besides people hating on poor Carl Grimes) is that there aren't ENOUGH of the titular characters on the show. Season Two was derided as "The Talking Dead" and when compared to the more recent seasons of the show, it feels admittedly underwhelming. At this point, people seem to love zombies, but it's hard to tell if they're actually scared of them.

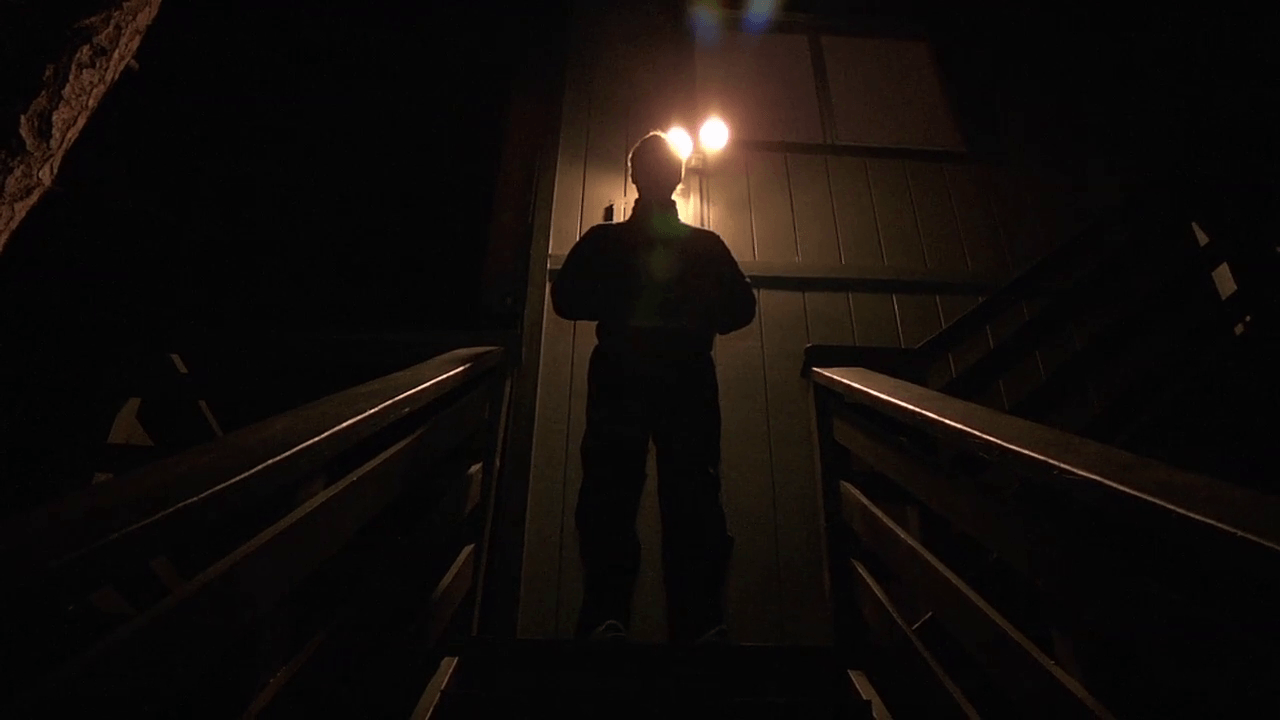

February, 2015

So what do people want now? Do they want to be scared, or do they just want to revel in the gore and blood? At what point does fear transition into the vicarious thrill of rooting for the good guys? The pendulum will always swing into the other direction and despite the overwhelming amount of zombie pop culture interpretations available, there are some who are taking it into different and interesting directions, as shown by the TV show iZombie or the recent comedy Life After Beth.

And there are always new versions of old ideas. For example, there seems to be a renewed interest in Satanic or occult-themed movies and TV shows, like February, for example, which is far more disturbing than any of the recent found footage possession films I've seen.

Since this new iteration of horror - the lurking danger of demons - hasn't yet been done to death, there are still plenty of opportunities for the discerning horror fan to seek out different ways to get scared. At least until the next trend comes along.

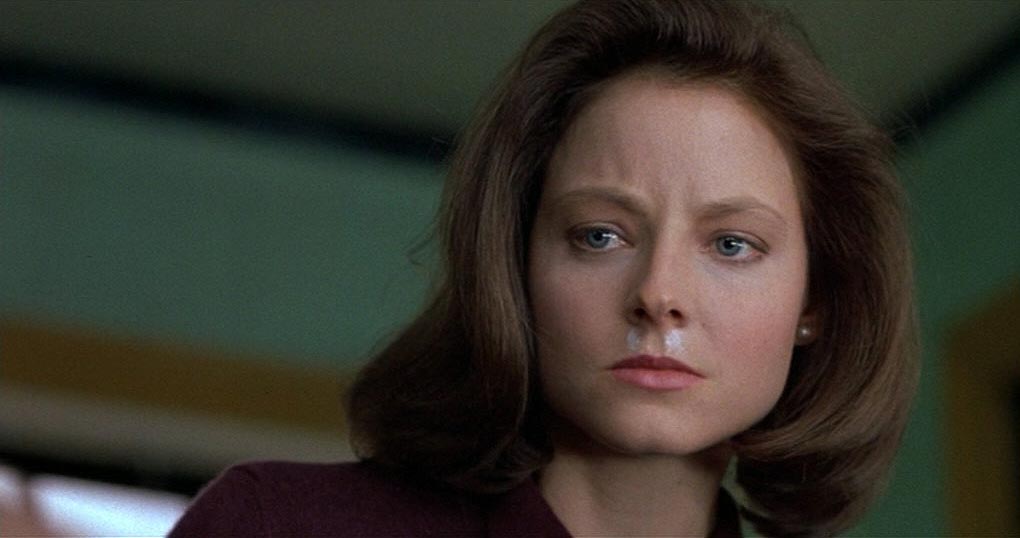

Since 34 episodes (and counting) of Hannibal are not enough to sate my bloodlust, I've been indulging in other pop culture iterations of the Hanniverse. Besides spending an inordinate amount of time on Archive Of Our Own and rereading parts of Thomas Harris's original novels, I've also revisited Manhunter as well as The Silence Of The Lambs.

In 1991, director Jonathan Demme wasn't considered a horror film director. Neither the screenwriter (Ted Tally) nor the cinematographer (Tak Fujimoto) were known for their horror bona fides, either.

Jodie Foster's passion for the role seemed to place her as the ideal cinematic version of Clarice Starling, though she was not considered a horror movie actress. Even though Anthony Hopkins was chosen because of his work in The Elephant Man, anyone who saw his role in Magic knew that he could play creepy as well as, if not better, than anyone.

On IMDB, The Silence Of The Lambs is listed as "Drama, Mystery, Thriller" and while it does contain elements of all three, it's considered a horror film by many. Still, it may have been the other categorizations that allowed it to dominate the Academy Awards, with wins for Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, and Adapted Screenplay.

In the ensuing years, we've seen so many ludicrous spoofs of Hopkins as Lecter, that his portrayal of Hannibal the Cannibal has lost a lot of its luster. Like a lot of things in pop culture, people remember the imitators, not the originators, and judge the latter by the quality of the former, an unfortunate mistake.

When I saw Silence in theaters in 1991, admittedly, I was a horror newbie, but I found it terrifying. I wondered if it would still hold up after so many years and seeing so many more horror films. The answer is yes.

Composer Howard Shore, although he might be more familiar to younger viewers for his work on The Lord of the Rings films, had a history of scoring horror films: by 1991, he'd already worked on five David Cronenberg films. Part of what makes Silence work as a horror film is the score. It's suspenseful and emotional without being maudlin or clichéd.

Unlike Manhunter - the novel and the film - by Silence, we have already been introduced, albeit briefly, to Hannibal Lecter, so we think we know what to expect. Here we meet Clarice Starling for the first time and Demme wisely piggybacks off of Harris's already well-written character by allowing us to truly see things through Clarice's eyes.

It's Foster's steely yet sympathetic portrayal of Clarice that allows Hopkins's Lecter to be that much more menacing and the film as a whole to be utterly frightening. The F word itself is never used, but there are several allusions made to Starling's feminism: she reminds Dr. Chilton that UVA isn't a charm school and calls Jack Crawford out on his "Clarice, the men are talking" speech at the West Virginia morgue, in addition to brushing off Lecter's pointed sexual questions with a "That doesn't interest me and, frankly, it's the sort of thing that Miggs would say."

Despite her seemingly tough exterior, when she first encounters Hannibal, she's clearly daunted, and who wouldn't be? He's kept in a room that looks like a dungeon and she gets a slew of warnings from both Chilton and Crawford about not engaging with him. The buildup doesn't detract from the film's eventual reveal. In his cell, Hopkins looks akin to Boris Karloff's Mummy, but instead of dead, soulless eyes, his are bright blue and penetrating, extracting your most secret thoughts and fears. Hopkins's vaguely amused face and unblinking, wide eyes are truly unnerving.

Buffalo Bill a.k.a Jame Gumb, while also monstrous, is a different kind of bad guy, albeit one into whom Lecter has quite a bit of insight. When we see Gumb struggling with a broken arm and a couch outside of a windowless van, we know that it's not going to end well for poor Catherine Martin. His viciousness is further demonstrated when we see the waterlogged corpse of his most recently discovered victim displayed in West Virginia. The reactions of the men present show their obvious terror and disgust, but Starling exudes pure empathy. It's that quality which makes our own eventual view of the body that much more horrific. She is more than a just a victim, and Clarice bestows a dignity and human quality upon her, much like the one Senator Martin hoped to convey for her daughter through her televised plea to Buffalo Bill.

It isn't until later in Silence that we see Hannibal Lecter in predator mode and by then, we've almost become accustomed to his quirks. (By then, we've also witnessed the "it rubs the lotion on its skin" scene.) The need to have over a dozen cops creeping through a building with guns drawn might seem like overkill, but when Lecter savagely murders Sergeant Pembry and displays Lieutenant Boyle's corpse we are reminded that he isn't some quirky, demanding college professor, but a genuine, real-life monster.

Although Lecter is now on the loose, Clarice must focus on Gumb, and in the end she is the one who must face him. Her terror in his dark basement is palpable, with his night vision POV foreshadowing the aesthetic most of the found footage canon. Blinded and beyond fear, Starling is both completely out of yet totally within her element. She takes out Gumb like a pro, despite trembling the entire time, and it's a beautiful, heroic scene, sort of like Rachel McAdams's Ani Bezzerides in this season's True Detective shootout sequence, minus all the swearing.

By the time Lecter calls Clarice at her graduation party, she's already dismissed the idea that he would harm her. We see him slowly stalking Chilton, but only Chilton's grandmother could have sympathy for him at this point in the film. Clarice Starling shares something with Hannibal Lecter, and although she isn't a murderous psychopathic cannibal, that's enough to drive home the point that the monster walks among us.

Swiggity swag Cronenstag.

This past week's installment of Hannibal, "Primavera," featured one of the more revolting scenes of the show (which is saying something). During one of Will Graham's empathing episodes, a skinned, dismembered, reconfigured corpse comes to life, sprouts hooves and antlers, and moves menacingly towards him.

Show creator Bryan Fuller dubbed the creation "Stagenstein," while production sketches for the show called it "Stumpman." (I'm partial to my own term, "Cronenstag.") This concoction is more grotesque than Mason Verger eating parts of his own face in Season Two's "Tome-wan." I remained fascinated and could not look away, even rewatching animated GIFs of the Cronenstag on Tumblr.

I've talked before about "the uncanny," in which things are both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. Somehow Cronenstag seemed worse to me. On the one hand it was a wet, fleshy creature that moved realistically. On the other hand, I know in my gut that it isn't real. So why the disgust and fear?

In many ways, this scene reminded me of the film Splice. (Vincenzo Natali, who wrote and directed Splice, also directed "Primavera.") The movie is one of the best examples of that Mystery Science Theater 3000 cliché, "he tampered in God's domain."

Two scientists (Elsa and Clive) develop animal hybrids for a genetic research company. Explicitly prevented by the company from adding human DNA into the mix, they conduct their human/animal hybrid genetic research in secret, eventually giving birth to a creature they refer to as "Dren." Dren is decidedly creepy and looks not totally unlike Hannibal's Cronenstag, with her spidery limbs and hoof-like feet.

Again, watching Splice I know that Dren is a cinematic creation and thus unreal. Still, Splice is one of the most disturbing and unpleasant films I've seen in recent memory precisely because it's so obviously unreal but could very well exist. As Natali noted in an interview on the film: "The centerpiece of the movie is a creature which goes through a dramatic evolutionary process. The goal is to create something shocking but also very subtle and completely believable."

Natali has explained in several interviews that the idea of Splice came from his encounter with the Vacanti mouse. In this experiment, scientists seeded "cow cartilage cells into a biodegradable ear-shaped mold" and then implanted it "under the skin of the mouse." (As an odd side note, the "nude mouse" on which the structure was grown is not a genetic experiment, but a spontaneous genetic mutation.) Are we repulsed by these images because we don't want to accept that such genetic experiments could actually be real? After all, the advent of cinematic technology has developed hand in hand with scientific technology; what filmmakers can create visually may not be so far removed from what scientists have created in labs.

Dren isn't the only creepy thing in Splice. Elsa and Clive also develop a pair of seemingly amorphous blobs named Fred and Ginger. These critters have been copyrighted and will be used to create livestock feed (an ethical quagmire in its own right). Fred and Ginger, like Dren, resemble what an article on sculptor Patricia Piccinini refers to as "parahuman." "Piccinini's parahuman beings are both uncannily real and somewhat disturbing. Certain people have a hard time with these works or find them so disturbing they can't stay near them."

Parahuman creatures like Cronenstag, Dren, or Fred and Ginger all recall what bioconservative scientist Leon Kass has called the "wisdom of repugnance." From Wikipedia: "In all cases, it expresses the view that one's 'gut reaction' might justify objecting to some practice even in the absence of a persuasive rational case against that practice." Since the "wisdom of repugnance" can also be used to justify prejudice against others on the basis of race, sexual orientation, disability, and a host of other factors, it's a problematic concept that has been the subject of much criticism. It can be argued that such prejudices reveal more about the repugnant qualities of the person who is objecting to another entity, i.e., that he is himself racist, sexist, or ableist.

In the case of Splice and the Cronenstag at least, repugnance is still a real reaction to something seemingly unreal. It begs the question: at what point does fascination veer into disgust or disgust into fascination? That's the precise kind of liminal space that both Splice and the Cronenstag occupy. It's a question whose answer can't be predicted, and that's scary.

NBC's limited series Aquarius premiered on May 28, with the remaining 12 episodes going up on NBC.com the subsequent Thursday. Aquarius attempts to add a new spin on the events leading up to the Tate-LaBianca murders that took place on August 9 and 10, 1969.

Opening in 1967, the show follows multiple intersecting narratives: police sergeant Sam Hodiak (David Duchovny) investigates an "off the books" missing persons/kidnapping case for his ex-girlfriend Grace Karn (Michaela McManus). Grace's 16-year-old daughter Emma hasn't been seen or heard from in four days. Her father, Grace's husband Ken (Brían F. O'Byrne) is a well-connected, high-powered lawyer who wants to keep the potentially politically damaging scandal out of the press. As it turns out it's Charles Manson (Gethin Anthony) who has lured Emma away from home. Hodiak investigates the case with his younger partner Brian (Grey Damon), who thinks of Hodiak as a square.

David Duchovny is pretty terrific as Hodiak. As for Aquarius, it's no Mad Men, but I'm five episodes in and so far it's has done a decent job of creating a sense of the social and political unrest of the time period, with ongoing threads about drug use, hippies, and racial unrest, including a character that is a member of the Black Panther party. For those who have read extensively about or lived through the Summer of Fear: 1969 Edition, however, Aquarius doesn't do the best job of toeing the line between fiction and reality as far as Charles Manson is concerned.

Aquarius

Admittedly, it's a difficult balancing act. How does one present a compelling portrayal of the horrific events of the late 1960s to a world in which Manson is seen as a pop culture icon, especially when there have been so many fictionalized versions of the story already? Aquarius is a little more edgy and believable than say, the 2004 version of Helter Skelter with Jeremy Davies, but this is network TV, after all, and the show frequently stumbles, especially with its portrayal of Emma and the burgeoning development of The Family.

Although the Tate-LaBianca murders themselves were savage and unprecedented, even at a time when people were being slaughtered en masse overseas, what makes the Manson murders so unique are their origins. After all, The Family was a cult that Manson concocted after flirting with a variety of New Age religions like Scientology and The Process Church, among others. The intervening years have seen no shortage of cults who've killed in the name of someone or something: Peoples Temple, Heaven's Gate, Branch Davidians. Yet the Manson case stands out because the murder victims weren't actual members of the cult.

There have also been a lot of fictionalized portrayals of these cult tragedies, such as Ti West's The Sacrament, a found footage pseudo-documentary that recasts the events of 1977 Jonestown through the modern lens of Vice journalism. Despite this ambitious premise, the movie isn't shocking or scary at all, especially if one is familiar with contemporaneous news articles and photos.

A much better movie about cult activity and its impact is 2011's Martha Marcy May Marlene, about Martha (Elizabeth Olsen), a young woman who has recently escaped from a cult. The film alternates between the current narrative world of the film and Martha's flashbacks, often blurring the divide between dreams, memories, and even reality. It's one of the most frightening movies I've ever seen that isn't a straight-up horror film. John Hawkes plays cult leader Patrick as a wild-eyed, magnetic sleazebag who is legitimately, skin-crawlingly awful, far more disturbing than Gethin Anthony's clichéd, bisexual redneck on Aquarius.

Martha Marcy May Marlene

In "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," feminist scholar Laura Mulvey's seminal 1975 essay on the Male Gaze, she argues that because straight men make the majority of movies, women become objects to be looked at and thus, lose their agency. This is part of why Aquarius fails at this task and why Martha Marcy May Marlene, a movie that isn't even about Charles Manson, succeeds.

Even though it was written and directed by a man, Sean Durkin, the key to what makes Martha Marcy May Marlene so successful at being scary is its focus on Elizabeth Olsen's character: someone who's been completely shattered. We see things through her eyes and it makes everything that much more believable. This is the problem with Aquarius: by taking us on this journey with Sam Hodiak as our guide instead of Emma, we don't get the same perspective. We see things happen to Emma; we aren't privy to how she feels about what happens to her.

In Aquarius, Emma feels like a character in everyone else's story but her own: her parents, Charles Manson, Sam Hodiak himself. It's not about her situation; it's about the problems it causes everyone else. The show lavishes more care on a ridiculous subplot in which it's revealed that Ken Karn is not only gay, but was once Manson's lover, in addition to being his former attorney. It's a little too predictable, when a story about one of the most famous serial killers of all time should be far more wanton in its approach.

Even though it's a recent song, Lana Del Rey's "Ultraviolence" manages to create more of a mysterious, malevolent vibe than much of Aquarius (at least so far). In an interview with Grazie magazine, Del Rey states,

"I used to be a member of an underground sect which was reigned by a guru. He surrounded himself with young girls. He thought that he had to break people first to build them up again. At the end I quit the sect."

Fans have speculated that she's referring to the Atlantic Group, an unofficial offshoot of Alcoholics Anonymous long condemned for its cult-like activities.

With lyrics like "he hurt me but it felt like true love" and "you're my cult leader" set to a brooding orchestral background and the repeated alliteration of the words sirens, violins, and violence, "Ultraviolence" conjures up a more personal and therefore affecting picture of the ways that a cult can destroy, especially young and vulnerable women. Considering that the Atlantic Group is a current entity, it makes it seem like the idea of another Charles Manson isn't something that happened 40 years ago, but something contemporary and genuinely scary.

I'll keep watching Aquarius because it is ambitious despite its flaws, but I'll also keep hoping that perhaps one day a filmmaker or TV network will capture the creepy crawly feeling Ed Sanders did in his 1971 book on Manson, The Family.

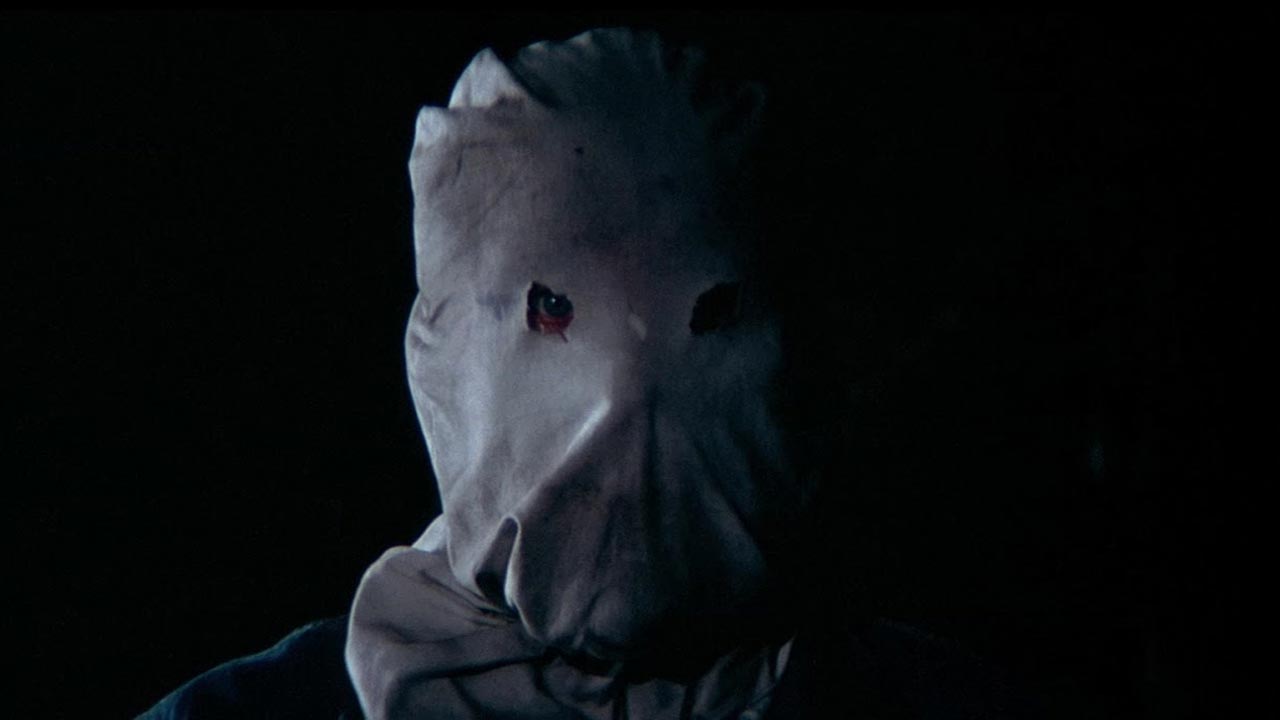

The Town That Dreaded Sundown, 1976

On the recommendation of a friend, I watched the Killer Legends documentary that is currently available on Netflix Canada. Like pretty much everyone I know, I am fascinated by urban legends. Killer Legends is directed and narrated by Joshua Zeman, who used his own film Cropsey - an exploration of an urban legend that transformed into a true crime documentary - as the template for this, his second documentary.

I have not seen Cropsey, but Killer Legends hooked me immediately. Granted, the music and narration tends more towards melodrama and less towards the subtler end of the spectrum, but once you get used to that, it's not too much of a distraction. The stories Zeman and assistant director/producer Rachel Mills have chosen to highlight in Killer Legends is solid enough to forgive those stylistic quirks.

Killer Legends addresses four different urban legends and examines what real life horrors may have inspired them, cleverly intercutting between Zeman and Mills researching and interviewing people and horror movie clips that traffic in the same kinds of narratives that feed the urban legends themselves: Lovers Lane stalkers, poisoned Halloween candy, babysitter murders, and creepy clowns. It's incredibly illuminating to discover the real-life events behind the reel life ones depicted on big screens.

It also reveals insights into the ways we process horror. The conclusion that Killer Legends eventually draws is that urban legends play a role similar to that of horror films: they help us deal with the horrors of real life. Early on in the film, Zeman remarks on how the annual screenings of pseudo-documentary The Town That Dreaded Sundown in Texarkana, the same city in which the Phantom murders that inspired the film took place, push the bounds of good taste. After all, he points out, the families of those murder victims still live in the same town.

I admit that it did give me pause, but then I started thinking about the reasons why I watch horror movies. I was always one of those people too scared to watch them. Oh, I saw plenty of horror movies in my life, but they often terrified me long after the credits rolled, giving me nightmares and anxiety attacks. An attempt at watching The Texas Chain Saw Massacre when I was in my late twenties freaked me out so badly I had to stop the tape right when Leatherface grabs Pam and throws her up on a meat hook.*

After I had a nervous breakdown in 2007 however, I embraced horror with a new-found, and perhaps alarming to some, passion. If I could make it through wanting to kill myself, I thought, I could make it through any horror movie, because those weren't real. Granted, I also found a lot of comfort in films like Let's Scare Jessica To Death because I related strongly to the characters, but horror films in general suddenly felt like a safe space for me to examine the politics of fear.

What disturbed me most in Killer Legends were the crimes that inspired the legends, especially the crime scene photos. These weren't stills from a movie set; these were real people who were raped, beaten, and killed. They weren't subjected to this brutality so that I could examine my relationship with fear; they were victims of horrible tragedies.

This is why I think it's acceptable, and in many cases even necessary, to examine such tragedies through the lens of horror pop culture. Perhaps the fictionalized versions of these horrors can provide the distance we need to process what we could not face otherwise.

*By the way, I finally watched all of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre a few years ago and loved the hell out of it.

Have you seen The Pact? You'd be forgiven if you skipped over this 2012 horror release due to its generic title and bland poster art. Then again, you'd be missing out on a truly effective chiller.

Nicole Barlow is tying up loose ends after her mother's recent death. She's a recovering drug addict so when she doesn't return phone calls, texts, or emails for a 24-hour period, her sister Annie blames it on a relapse. Then Annie finds Nicole's cell phone in the same closet in which she and her sister were banished when they misbehaved as children. When their cousin Liz vanishes in the middle of the night, Annie starts to suspect that something more sinister is at play.

The Pact uses simple but arresting imagery to startle the viewer. All of the visuals make up a vital part of the narrative; there are no throwaway scares here. Although several of these images continue to haunt the viewer long after the credits have crawled across the screen, what is most important to the story in The Pact is the house.

Many haunted house films tend to be set in old, crumbling Victorian or Gothic mansions which, let's face it, are pretty ominous and imposing on their own. But The Pact isn't exactly a haunted house movie. What makes the film unique is the utterly ordinary quality of the home that resides at the center of the terror. The opening of the film is a slow tracking shot through a narrow hallway that is covered in busy, 1980s style wallpaper. It doesn't seem that creepy at first, but it soon will be.

From the beginning of the action in the film, the house has a distinctly unnerving presence. Filmmaker Nicholas McCarthy uses a specific color palette of yellow and black through the set design and the camera filters, which casts a shadow of queasiness over this very believable place.

Many homes depicted in horror films don't appear real: they're too modern, too clean, too perfect. This is not the case with the Barlow home in The Pact. The furniture is old and threadbare and the carpet and flooring are dingy. Overall, the Barlow home is cluttered and claustrophobic. It looks like the house of someone who recently passed away unexpectedly. It looks real.

There is also a preponderance of religious iconography in the home which suggests that someone in the home was either deeply religious and that such artifacts would ward off some kind of evil. Again, it's subtle but effective; Mrs. Barlow's religious convictions are not mentioned specifically by any of the characters. We only see it in visual terms.

It isn't just that "bad things" happened in the Barlow home, in the form of Mrs. Barlow's abuse of her daughters. It's that something evil literally does reside in this home, in a hidden room that Annie did not know about until now. This isn't the typical "pull the book from the shelf, and it reveals a secret passageway" kind of hidden room. It has been dry-walled and wallpapered over and only shows up in the original blueprints of the house.

Not only does the house in The Pact look like something out of a nightmare - which is further reinforced by that same slow tracking shot through the hallway comprising the bulk of Annie's nightmares in the film - it actually houses a palpable evil in the form of Erik Barlow, who is a serial killer.

Perhaps the film's unimposing title and seemingly uninteresting poster are both perfectly suited for a film that's a lot scarier than it might initially appear.

It Follows has become a minor cinematic sensation. It cost about $2 million to make, but has already made eight times that amount in domestic profits (1). Certainly box office numbers aren't indicative of a film's quality, but they can indicate that its narrative themes have tapped into the cultural zeitgeist.

It Follows tells the story of Jay, a college student, who has been cursed with a sexually transmitted phantom. If you think that sounds like a ludicrous plot, you're not alone, because I felt the same way before seeing the film. But like another film regarding sexual trauma and the supernatural, 1983's The Entity, It Follows manages to be genuinely frightening. WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD.

Unlike a lot of horror films featuring young adults, It Follows is not a slasher film, but it's no less harrowing. Instead, it feels like a paean to Gothic literature. So what is "Gothic" anyway? As feminist literary critic Ellen Moers states, "But what I mean - or anyone else means - by 'the Gothic' is not so easily stated except that it has to do with fear." (2)

More specifically, Professor Douglass H. Thomson has isolated seven "descriptors" of the Gothic. 1) the appearance of the supernatural, 2) the psychology of horror and/or terror, 3) the poetics of the sublime, 4) a sense of mystery and dread, 5) the appealing hero/villain, 6) the distressed heroine, and 7) strong moral closure. (3)

The titular "it" of It Follows is decidedly supernatural: it cannot be seen by anyone but its victims and it cannot be killed, only temporarily thwarted. The various forms the supernatural stalker takes in It Follows also play on the Gothic trope of the doppelgänger, a "ghostly counterpart" or "alter ego." It looks like a human, but an abject human, a transgressive entity that appears aged, diseased, wounded, or in a few particularly disturbing scenes, much like a rape victim. (This also plays on Freud's "uncanny.")

Another thing that differentiates It Follows from a slew of horror movies about young adults is the lack of explicit gore, and in this the film relies more on the Gothic psychology of terror - creating "a sense of uncertain apprehension that leads to a complex fear of obscure and dreadful elements" - and less so on "horror," or "a maze of alarmingly concrete imagery designed to induce fear, shock, revulsion, and disgust." (4) Although some of the imagery within the film induces horror, the origins of the curse are unknown and thus, obscure.

The poetics of the sublime are another characteristic of the Gothic found in It Follows. Although the exact definition of the term varies from writer to writer, the awe-inspiring aspects of nature are at play in the sublime. Jay spends time floating in her backyard pool, staring at the trees and the sky beyond; she and her friends flee to a beach house, traveling through the colorful fall foliage to enjoy the quietude of the sand and water.

Jay's escape into the sublime is more pronounced after her experiences with the mystery and dread of the Gothic "ancestral curse" that her ex-boyfriend Hugh has given to her. What could be more mysterious and dreadful than constantly looking over your shoulder for a fiend that looks like a human but which is definitely inhumane, a ghastly apparition that will kill you if it gets too close? As Jay's ex-boyfriend Hugh puts it, "It's slow, but it's not stupid."

In this way, Jay is both the appealing hero (we want her to escape her fate) and the distressed heroine, specifically the Gothic "pursued protagonist" which:

"refers to the idea of a pursuing force that relentlessly acts in a severely negative manner on a character. This persecution often implies the notion of some sort of a curse or other form of terminal and utterly unavoidable damnation, a notion that usually suggests a return or 'hangover' of traditional religious ideology to chastise the character for some real or imagined wrong against the moral order." (5)

After Jay has consensual sex with Hugh, he chloroforms her and ties her to an abandoned wheelchair, where he explains that she's now been cursed as he waits for "It" to show itself. He then quite literally drops her off at home: she's abandoned in the middle of the street in her underwear. The police are called and she undergoes a rape test in the emergency room.

Her shame and guilt are made manifest the next day when she examines herself in the mirror, like the way rape victims feel as if others will somehow be able to see or intuitively "know" that someone has been raped. Jay verbalizes these feelings to her family and friends when It breaks into her home, asking them why this is happening to her and begging them to believe that it actually has happened.

In order to rid herself of the curse, Jay must pass it on to another person. She is hesitant to do so, but finally relents, sleeping with neighbor Greg. Unfortunately, he is killed by It, and so Jay, according to the "rules," is next in line to be killed. Again, she is hesitant to pass the curse onto her friend Paul, who's had a crush on Jay for years, but eventually she agrees, and they sleep together. The film ends with Paul and Jay holding hands and walking down the street. This represents the Gothic ideal of a strong moral closure in which sexual relations are embarked upon with purpose and gravity, in opposition to the way that Hugh originally contracted the curse: a one night stand.

Regardless of its adherence to the conventions of Gothic literature, It Follows is a remarkable accomplishment in horror cinema: an engrossing, thoughtful narrative about the symbiotic social relationship between sex and shame that is also downright terrifying.

Many film fans and filmmakers have recently expressed a desire to go back to the basics, aesthetically speaking, insisting that what you don't see in a horror film is scarier than anything conjured through CGI. They argue that smaller budget films are often more effective than tentpoles because financial restrictions force the filmmakers to be creative when devising ways to provoke an audience into fear.

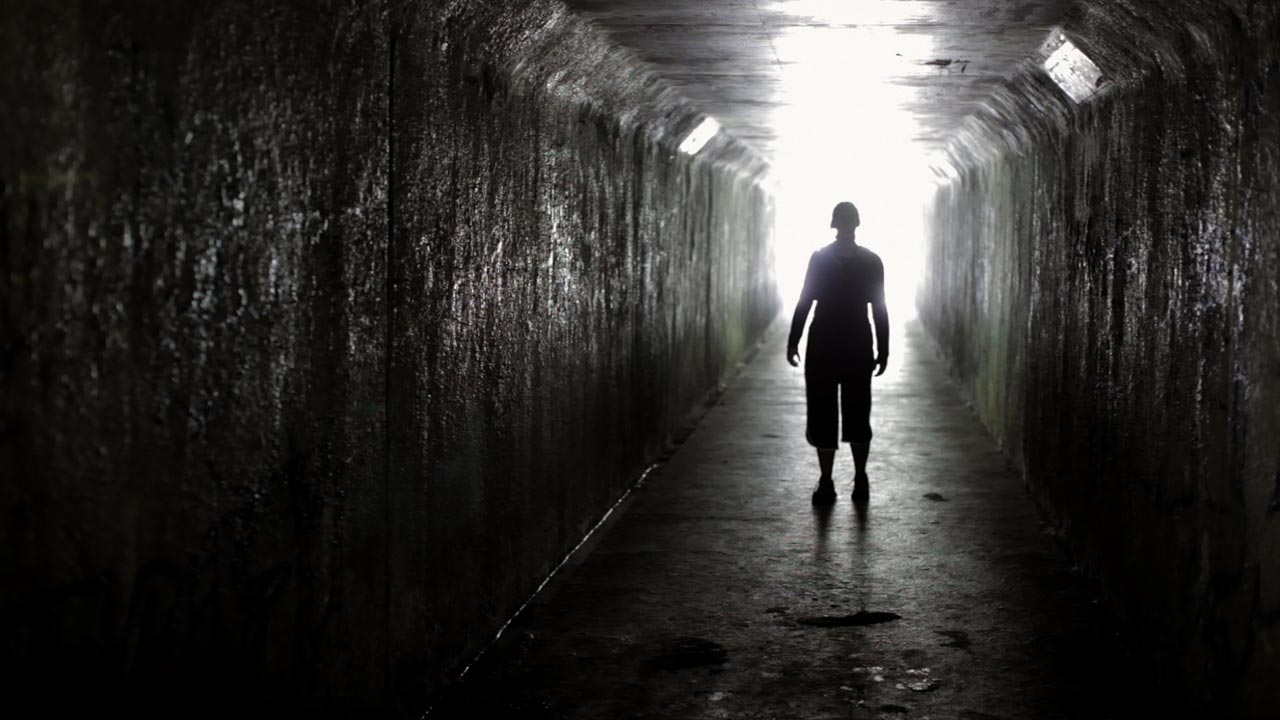

A beautiful example of this theory in practice is Mike Flanagan's 2011 film Absentia. It treads some of the same ground as Flanagan's more recent Oculus, in which a family is tormented over the years by a haunted mirror. In Absentia, the object in question is a tunnel connecting a Southern California subdivision to a nearby park.

Tricia's husband Daniel vanished seven years ago. No body was found, and after much anguish, she decides to have him declared dead "in absentia" for both legal and personal reasons. Her sister, Callie, a former runaway and drug addict, visits Tricia to help with the process of moving on and moving out of her apartment to begin again. Tricia his also pregnant, and offers no clues as to the identity of her unborn child's father, but she has embarked on a tentative relationship with Ryan, the cop in charge of Daniel's missing persons case.

Just as things seem to be progressing in a positive direction, Daniel shows up, both physically and psychically damaged, with only vague, nonsensical ideas of where he's been for the better part of a decade.

So much of Absentia's frightening aura comes from unreliable narrators: Tricia because she has lucid dreams of a black-eyed, enraged Daniel; Callie because, although she claims to be sober, she's still surreptitiously using drugs (though we don't see her in the act); Daniel because he speaks of a thing in the walls that's trying to get him.

When awful things start taking place in Absentia, we don't actually see them, only hints of them. Sounds and movements out of the corner of the eye; people who appear out of the shadows but aren't really there; a homeless man in a tunnel, begging for help and raving about nameless creatures. Such occurrences could easily be explained away.

There are a lot of typical problems in Absentia: flyers for missing people (including Daniel) and pets are pasted on telephone poles and there have been a series of petty burglaries in the neighborhood. We see these things so often they barely register with us anymore. Then there are the more personally upsetting, but still commonplace misfortunes: unpaid bills, legal paperwork, troubled marriages, broken families, single motherhood and addiction. Finally, there are fantastical issues that plague the characters: the alleged existence of a city underneath the ground, where humans are kidnapped by a monster with skin like a silverfish.

In Absentia, all of these events are connected. Furthermore, the gravity of these various tragedies shifts from banal to otherworldly and back again before the characters-or indeed the audience members-are aware that such a shift is taking place. Trying to explain it to someone who can't or won't understand - much like Callie does with Tricia - is met with disbelief. "It's easier to embrace a nightmare," says Tricia, "than to accept how stupid - how simple - reality is sometimes."

But what if the answer is both a nightmare and reality? Much like the tunnel that connects the characters to the horrible thing that holds sway over them, Absentia occupies that liminal space between reality and unreality. Was the silverfish crawling in the sink just a bug or a harbinger of something worse? Is Daniel a paranoid schizophrenic? Did Tricia imagine his appearance or was he truly there? Was Tricia spirited away by the thing in the tunnel or did she cut herself off from the grid to start her life over again?

There's a scene in the film where Tricia and Callie are turning out the lights to go to bed, and Callie hears a noise. The camera cuts to a shot of Tricia, staring into the black nothingness of her living room. But instead of a void, there's a monster in there that literally takes her away. We never see the monster, but Tricia's absence is as palpable as its presence. Later Tricia scrawls, "beware the things underneath" on a note she leaves for Ryan.

This liminality is what makes Absentia genuinely terrifying. It feels like the events in this film could happen to anyone, even us. If that happened, then who would believe us? We are all unreliable narrators of our own lives in a way; our experiences and prejudices color our perceptions of what we see. We can never totally be sure of our own objectivity and that sure scares the hell out of me.