Another Halloween has come and gone. I always get depressed on the first of November because, as you can probably guess, Halloween is my favorite holiday.

It’s not like I wait until October 31 to celebrate. I start decorating and listening to my Halloween playlist the first week of October. I often start planning my costume months in advance and I’ve been making my own costumes for well over a decade now. From my posts on this site, it’s obvious that I consume horror media on a near-daily basis. So why is it so important to me to celebrate this one day out of the whole year?

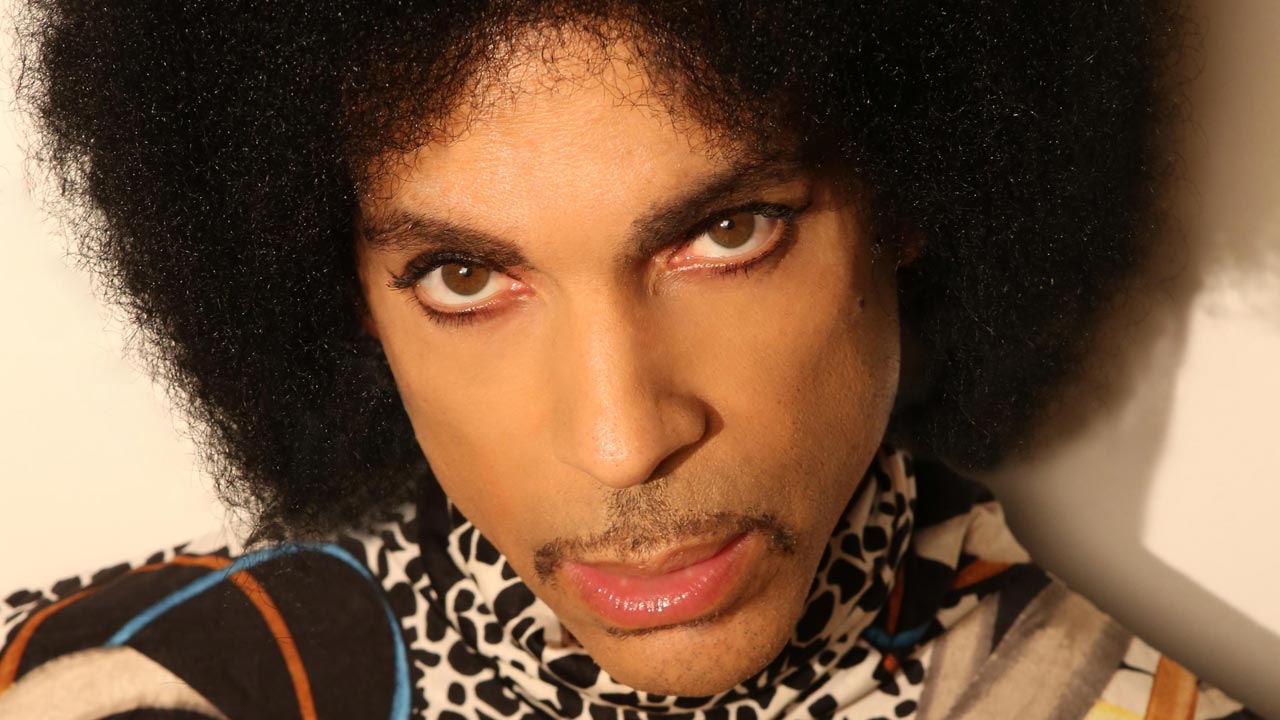

As much as I am OK with being considered a weirdo by some folks for being such a Halloween and horror junkie, it still feels immensely satisfying when so many other people are into the same things I am into, even if it’s only for part of the year. (And as someone who tends to choose esoteric or obscure costumes, all the positive attention I got this year for dressing as Papa Emeritus III from Ghost was even more immensely satisfying. That time that I dressed as Adam Ant and people asked if I was Prince? Not so much.)

Recently, I came across some social media commentary from people who didn’t understand why anyone would enjoy watching a horror movie. Different strokes and all that; besides, it’s certainly not the first time I’ve seen that sentiment expressed. I also came across a social media discussion, however, that was all about how seeing adults dressed up in Halloween costumes was disturbing or even scary.

This is utterly alien to me. Maybe it’s because I grew up in New Orleans and Mardi Gras is such a huge part of the culture there, maybe it’s because I took dance for ten years and costumes were an integral part of those performances, maybe it’s that I’m an exhibitionist at heart.

Now that so-called geek culture has become such a part of the mainstream, the cosplay community has been thrust into the world spotlight. Cosplayers, in some ways, get the side eye more than horror fanatics because they don’t even need the excuse of a holiday to get dressed up. Their lives are organized around which cons they’re going to attend and what costumes they are going to make and wear at these cons.

It makes me wish that Halloween cosplaying was a thing, although for a lot of people, it kind of is. When you attend any horror-related events like film screenings or conventions, you’ll notice that there are a lot of people wearing horror movie T-shirts. If you can make a valid case that cosplayers are just transforming themselves – via costumes - into characters that they feel represent their personalities, can’t we also argue that horror fans are doing the same thing, via Frankenstein tattoos and black clothing? Perhaps it’s not exhibitionism; perhaps it’s just letting the outside match the inside. (There’s a Morrissey quote in there somewhere…)

I feel the fear all year long, but that feeling is heightened at Halloween. On top of that, dressing up as someone or something else is empowering and exciting. I love that there is a day dedicated solely to both of these things. That’s why Halloween will always be my favorite holiday.