TANIS Podcast Review

The audio horror geniuses at Pacific Northwest Stories and Minnow Beats Whale have once again made something special. It’s called TANIS and it expands the universe of the extra popular podcast The Black Tapes, bringing the new wave of weird fiction to the Internet audioscape.

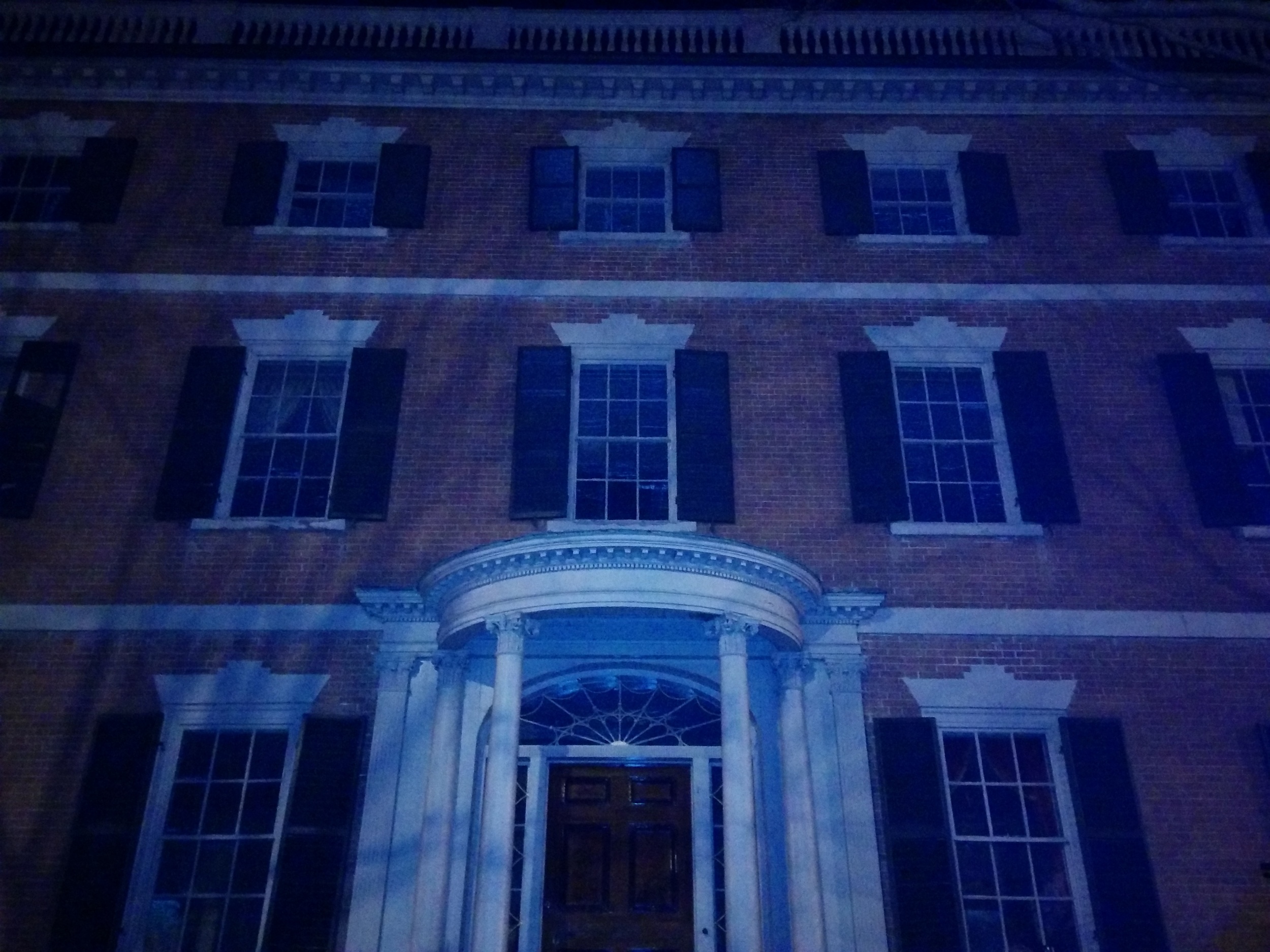

TANIS is the radio drama that H.P. Lovecraft never made. If The Black Tapes Podcast is The X-Files for your iPod, TANIS is Call of Cthulhu by way of Stamps.com (not a confirmed sponsor of TANIS). A serialized fictional investigation into a myth of an undefinable ancient thing called Tanis, the podcast follows PNWS producer Nic Silver as he navigates the missing pages of history and the obscure corridors of the dark web. His sleuthing unites him with an anonymous hacker who goes by the handle Meerkatnip, and eventually sets him in the sights of a seemingly malevolent interest that, at this point in the series, remains faceless.

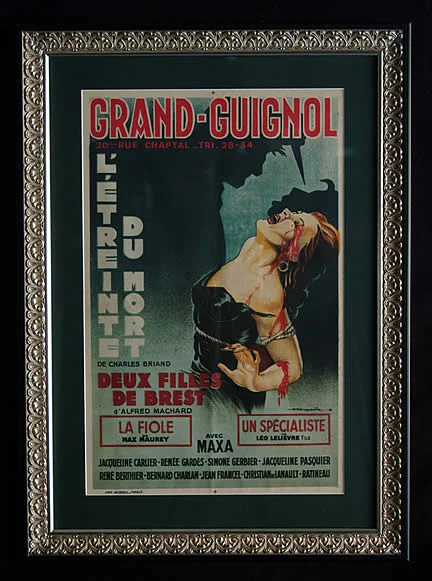

The narrative in TANIS is more focused than The Black Tapes. While the latter mirrors the paranormal investigator procedural format, pitting its protagonists against new phenomena each week, Nic Silver’s podcast solely deals with information on its eponymous entity-place. Much of the show deals with found texts and old interviews, revisionist history, and a sci-fi story from an old magazine, all of it serving to give Tanis substance and atmosphere without definition. Combine that well crafted historical revisionism with some grade-A creepypasta – like a ritual you can do in an elevator to access another dimension or a House of Leaves style cabin with uncanny measurements – and what you have is genuinely spooky weird fiction.

The name Tanis is simply one of many labels that has been given to Silver’s professional obsession over its thousands of years of alleged existence. Sometimes it’s a place, sometimes it’s a state of mind, but like the Great Old Ones of Lovecraft, or the celestial god terrors of William Hope Hodgson, we can only know Tanis through the humans who obsess over it. It moves and transforms, it inspires, and like a certain tentacled dreaming menace it builds a following.

As Nic chases down leads, researching, interviewing and connecting the dots, Tanis begins to gain atmospheric substance. We know Tanis through him. That’s why it’s so exciting when something inevitably starts to reach back from all the anecdotal evidence and historical blindspots.

The Lovecraftian horror tradition is largely built on the concept of alternate history built out of unknowable bits of past. As such, weird fiction can sometimes run the risk of being over expository and dry. If world events we normally take for granted are different in a story than in real life, it’s difficult to get that point across without lengthy explanation. Thankfully, TANIS dodges this pitfall by having fun with its research segments.

There are points in the show when Silver acknowledges the process of having other people reading text or compelling them to speak their experience out loud for dramatic effect. Such moments of self awareness help ground the presentation of contextual information in the present. The podcast format also helps turn the exposition into a tool for suspense, allowing Silver to frame the more chilling and active story points happening in the moment with relevant factoids from out of time. It allows for tension to build in the present day timeline while making sure relevant aspects of the dense mythology are ready at hand for when they are most needed in the story. Most importantly, it keeps the sense of discovery fresh.

TANIS is a strange story, well told. Tonally distinct from its sister podcast, The Back Tapes, Nic Silver's podcast shares one key similarity: it feels as real as I want it to be. The conspiracy at the show’s core is more interesting than mundane reality and the deadpan presentation is such a good imitation of NPR that some gullible first time listeners might mistake it for journalism. Tanis may be an undefinable entity out of time and space, but TANIS is a world I want to live in.