Horror That Says Hello

One of the base pleasures of horror media is voyeurism. The audience is a curious observer to another person’s very bad day and usually even more terrible night. No matter how painful the events are on the screen or page, you can rest assured, no matter how invested and empathetic you might be, you aren’t where the screaming is.

The role of the audience is a key aspect of horror, and one that’s been played with by storytellers throughout the genre’s history. Novels posing as found documents existed over a century before The Blair Witch Project, implying that the terrors within are matters of reality. The relatively recent subgenre of meta-horror - popularized (maybe invented?) by Wes Craven’s Scream films and finally done to death with Drew Goddard’s Cabin in the Woods - frequently trades in a balance of self-reflexive “aren’t movies funny and safe” humour with indiscriminate murder. The audience is safe to observe, and horror authors use this as a tool for thrills, laughs and scares.

In the recently concluded season of NBC’s Hannibal a sizable portion of screen time was spent deconstructing the responsibility of observers when it comes to watching horror. In the show’s season three premiere, Hannibal Lecter makes a big show about murdering a dinner guest in front of his captive beard Bedelia Du Maurier (Gillian Anderson), and before delivering the fatal touch asks her pointedly whether she is participating or observing. When the number of souls in the room goes from three to two, it’s clear that the question was meant to illustrate a point: to observe a horrific act is to participate, and to participate is terrible.

HANNIBAL: Observe this!

The relationship we have to the horror media we consume, therefore, is one of enablement. By turning on Carrie and watching all those teenagers burn to death, we are implicitly responsible for the on screen horror. When we watch Kubrick’s The Shining, we are agreeing to watch the poor old psychic groundskeeper to get axed right in the back. We watch the horrible things happen and we don’t do anything to stop it.

Obviously this is not a moral indictment of horror fans. The fantasy of horror is enabled by a safe space. We allow anything to happen on screen under the tacit agreement that everyone, including us, is safe despite what movie magic might imply. And that’s why it’s so goddamn chilling when works of horror challenge that contract with a threat.

There is a trope in horror that never fails to make my stomach turn and inspire in me an urge to climb up a wall in search of escape: when a supernatural force breaks the fourth wall. Two examples of it come to mind, The Ring and the playable teaser for the now cancelled video game Silent Hills (also known as P.T.) which was in development by Hideo Kojima and Guillermo Del Toro.

I could describe the instance of threatening wall breaking, but it will be much more effective to show you. Pay close attention around the 35 second mark of the following clip.

The woman brushing her hair in the mirror looks into the camera, which effectively means she’s looking at you the viewer. There is a great deal of imagery in the famous Ring tape that could be called more frightening, but none are nearly as threatening.

In P.T. the threat is slightly different. By virtue of its being a game, the options for meta-horror in the teaser are different. The entire experience is presented in first person perspective, so when an unhuman entity in the virtual world looks into the camera, the character actually shields you from the same uncanny effect in the above clip. Your access point for observation acts as a human shield. That said, the reality-threatening effect of Samara's mother looking at you through the screen is summoned by Kojima and Del Toro through their use of scripted crash screens.

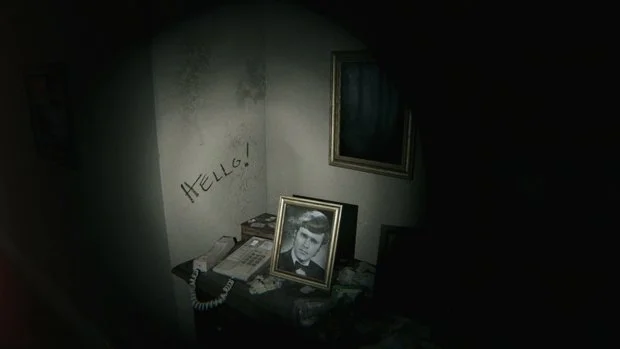

At a point in the teaser the screen begins to glitch and it leads to a threatening crash screen that, more than anything else, acknowledges your presence.

This is the most threatening of the many possible crash screens a player can be shown in P.T.

On paper the effect sounds campy and perhaps a bit tired. Popular games have been pretending to crash for dramatic effect since the mid 90’s. But in P.T. The event occurs well before you’ve come to the game’s completion, and so you as a player have been forced to remember yourself while experiencing the most horrific parts of the interaction. It’s as if the game, aware of its malevolence, pauses halfway through to say, “Hello, I know you’re there.”

The threat is tangible, even if it’s all in the name of unsavoury entertainment. Media that breaks its fourth wall like this understands that you are invulnerable as an observer, but asks you to test how confident you are in your safety. Even the most compartmentalized horror is created knowing that it will be experienced, so when you are made to stay up all night because of an idea in your head made by a scary book, that’s because someone did that to you. Horror is a sanctioned and safe act of cruelty, committed on you by an author. Sometimes the beast delivering the pain likes to say hi.