Duct Work: Real Adventures in Body Horror

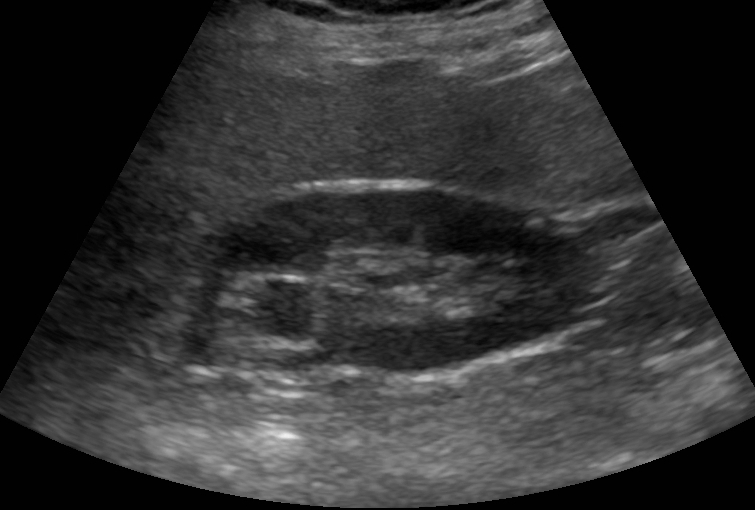

This is not my ultrasound. In fact, this might not even be from a human.

The ultrasound technicians laughed at me. Laying down on the examining room table, in the half-light apparently required for such a procedure and with my chin covered in the infamously cold imaging gel, I was ridiculed by technicians. The look underneath the skin of my jaw was turning up nothing, and so I pushed my tongue against the roof of my mouth to expand the region where one could clearly see the it - a small round anomaly in the flesh under my jaw - without a fancy schmancy college education. I even had a name for it, given to me by the doctor who sent me on this trial of humiliation.

It was a duct. When I was a foetus, like we all once were, my tongue was attached to my skeleton for support, like yours was too. The connecting tube, which is supposed to dissolve in utero, didn’t completely go away like yours all probably did, and the doctor was worried that he might need to surgically remove it lest my larynx become consumed by this mistake in God’s blueprint as repeated infections rotted my living face.

With inconclusive ultrasound results I had no tangible reason to have my throat cut open and therefore I drove home embarassed and more than a little unsettled. My duct problem first became an issue the summer before this failed attempt at medical imaging, when a little bump under my chin began to grow to the size of a pimple, then a marble and eventually a golf ball. The liberal application of antibiotics (to which I later became allergic) brought the swelling down and the blinding pain of it dissipated too, but a little round node remained, threatening to grow again but never quite becoming enough of a problem to call for invasive surgery despite my doctor’s concerns.

I have never really lived down the embarrassment of being laughed at in that dim ultrasound room. Part of the reason was that I was 17 and in a compromised (read: shirtless and prone) position in front of members of the opposite sex who were barely older than me laughing at a physical problem of mine, but mostly my social trauma has to do with the sequel to my first adventure in body horror.

Years after being told that my tongue duct problem was benign enough to ignore, the spectre of the angry red bump reappeared elsewhere. My encounter with the laughing technicians had made me wary of seeking medical advice when it came to body abnormalities, so when I found a bump on my upper, inner, upper thigh while showering I paid it no attention. But the horrors of the body don’t need your permission to grow, and so it did.

I also entertained the theory that it was a twin I consumed in the womb.

As the bump grew and memories of medial humiliation began to haunt my daydreams, I confided in my friend Katie about my plight by way of MSN Instant Messanger. She was, like all best friends, not supportive of my plan to just wait and see how this mysterious growth near my genitals situation panned out on its own. Her pleas with me to go to our university clinic went ignored though, because the social nightmare memories of past embarrassments, when combined with the fear of bodily metamorphosis, is a powerful force.

When we talk about fear of the unknown, which is cosmic horror, our gazes turn outward to the abyss in which we float, but that classic inclination ignores a terrifying truth about what lies within. Our bodies are fleshy vectors of the occult in its truest sense: filled with mysteries that have taken millennia to unlock. It’s the key to the body horror subgenre, the fact that inside each of our own bodies lies an intimate element of the unknown as strange as the darkness between stars

Eventually after neglecting my own intimate abyss for over a week I developed a limp. The new affliction had swelled to a familiar angry red vector of pain. School was out and I needed a job, so Katie and I had planned to hand out resumes at the mall on the contingency that I first go to our school’s clinic before hand.

Entering the office I asserted myself as a master of my own obscured condition. “I know what it is,” I told the receptionist. “I just need some antibiotics.”

Parenthetically I was trying to express a desire to not have to remove my pants. As the master of my own occult I wanted to keep it all hidden. I knew my body, didn’t I? Even if it was betraying me in a strangely familiar way. When the doctor met me in the room and I explained to her what I was asking for, she asked to see the abyssal pain point.

It took her only an instant to figure out what to do as I explained for the third time that antibiotics were the tried and tested solution for this kind of thing. “I have this duct,” I said.

“Our day surgeon is on lunch, but if you wait in the room across the hall he’ll be there shortly.”

When the surgeon entered I was instructed to remove my pants. His surprise was not comforting. The other worldly colour of the neo duct anomaly, along with its close proximity to my fragile and threatened humanity, meant that he would not be able to anesthetize the area before making four incisions with a scalpel and then removing the strange node with his fingers.

With the dignity of a man wearing socks, a shirt and tie, but no pants I made one more appeal for antibiotics, having been betrayed by a body that I thought was mine but instead belongs to forces indifferent to my knowing self. He said no, and then the cutting began.