The Numbers

Mr. Eko looks into the Swan Station hatch on LOST, which is a great show to watch if you have a lot of time on your hands.

We’re using up language to describe a down world.

Read More

Mr. Eko looks into the Swan Station hatch on LOST, which is a great show to watch if you have a lot of time on your hands.

We’re using up language to describe a down world.

Read More

Sorry Bela, we think you're cool now.

Dracula used to be scary because Bram Stoker’s audience was scared of immigrants. Things have changed.

Read More

The telltale sign that you’re close to a dead body, according to the movies and TV, is the razor sharp hum of a fly buzzing just out of view. I’ve never seen a fresh corpse in my life, so I can’t attest to this phenomenon of insectine pathetic fallacy, but I can say that flies are deeply connected to my idea of death. They feast on our dead flesh, lay eggs on us and rear children in the pools that were once functioning tear ducts - they thrive on our expiry as a reflex. We die and a thoughtless process begins, birthing countless black dots with wings.

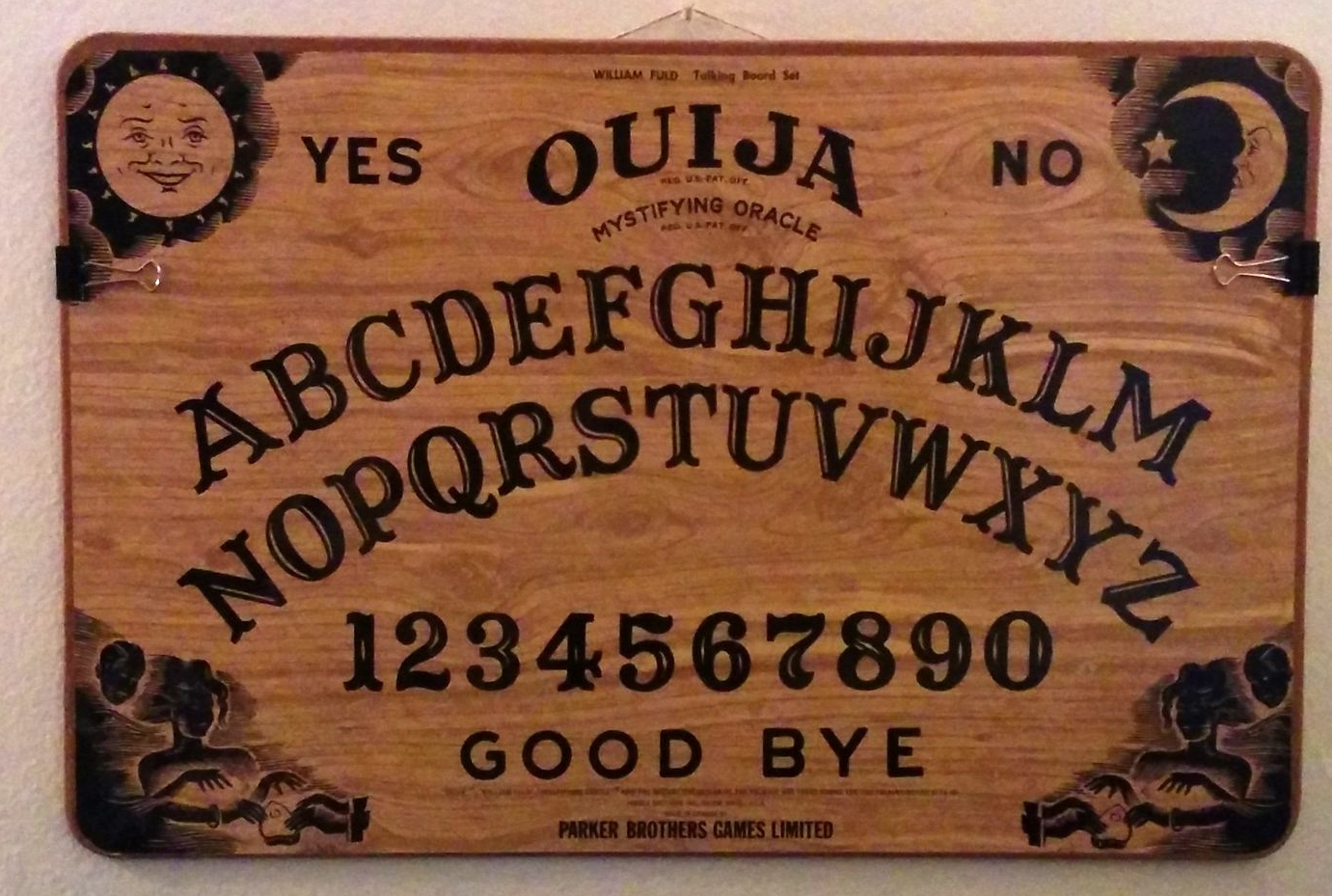

In the wake of my Oma’s passing, her four daughters converged on her remote house in the Lanark Highlands - a region of Ontario characterized by dynamite blasted roads and moths the size of Halloween masks. It was summer time, I was twenty-four, and my brother and I had joined my mother on one of these heirloom allocation expeditions. By the end of the day, I would come away with three items of various importance: a toolbox filled with my Opa’s wrenches and screwdrivers, an ornamental boomerang that I never got to work, and a Ouija Board from my mother’s childhood made before she was born.

Ouija is a lot like the boomerang I took from my Oma’s mantle. The designs printed on it are attractive, its status as a cultural symbol overshadows any practical use, and I can’t claim to have gotten either object to work in my favour. I stood on the lawn that day, surrounded by the rocky outcroppings that give Lanark such a unique atmosphere, and chucked that boomerang for what felt like hours, never getting it to curve through the air and return to me. It felt like using a piece of plastic and particle board to talk to the dead - something I can perfectly visualize in my minds eye, but can’t possibly achieve in real life.

For all the similarities, there is a key difference between the boomerang and the Ouija board. The hidden knowledge that can turn a curved stick into a boomerang is (I hear) learnable, but spirit boards run on things your mind will never share. The going theory on Oujia, as I touched on a couple of weeks ago when I wrote on the topic of evil board games, is that it exploits ideomotor response, which is essentially a reflex triggered by outside stimulus. Ouija conjures the illusion of conversation by allowing you to bypass your conscious mind. Wikipedia gives the example of a knee jerking when hit with a hammer (which is another item I had in my Opa’s tool box).

Having failed to discover the occult knowledge of the boomerang, I entered the house where my grandmother had died. Silver cutlery carpeted the floors, perfectly arranged by my aunts, and the many pendulum clocks the I had grown used to as part of the house’s architecture had, for the first time ever, become separate objects. When I would stay in my Oma’s home, I would sleep on the upper floor, with a door that opened up into the attic crawlspace that had always remained closed for reasons of scariness.

To access the stairs that lead to that room for visitors, I had to pass the room where my Oma had died. Prior to that moment, the chair room as I’d come to call it, was defined by two aspects. First, it was the room with the TV, so when we’d visit, my brother and I would hook up our Playstation in there. Second, it was the room with the sliding door that motivated my Oma to invest in a home security system.

She told my brother and I, at the same time that she told our mother (I think it was breakfast around the year 2000), that she had awoken in the middle of the night to the sound of loud banging. Exiting her bedroom, she followed the noise to the chair room, where a man stood in near complete darkness, opening and closing her sliding door. It's one of those heavy ones that makes a sucking noise when you open it.

That used to be the scary thing that happened in the chair room. Then my mother sat with my Oma as she died, exiting without using the historied sliding door or setting off an alarm.

I ascended the stairs with those ideas on my mind. My brother and mom were in the guest room looking through boxes with the door to the attic crawl space wide open. A single incandescent light was on, and it smelled like wood and maybe mothballs. I entered to see if I could find anything worth grabbing for myself that would rival the Jacques Cousteau Society sticker books by brother had found.

The main area was filled with old linens and clothes, but as I turned to exit I noticed a dark area that extended beyond the threshold of the door to its right, with a ball-chain indicating another light bulb. I pulled the chain and the dim light illuminated a familiar sight: a board with the words “yes” and “no” framing the letters of the alphabet and numbers zero through nine, underlined by a foreboding “goodbye”.

My moment of discovery was cut short with a hum coming from the light above my head. Looking up I saw it was covered with a swarm of large flies, all crawling and buzzing their wings; none were flying. I retrieved the spirit board and took it to show my brother and mom.

Things seemed darker. The light felt muted. My mother was excited to see her old game and I elected to keep it as part of my haul. The darkness felt tangible though, dampening my spirits, and I wondered if all my exploratory boomeranging had actually given me heat stroke, or maybe the grief of looting a dead woman’s house had tuckered me out. I returned to the main floor to grab a glass of water, intending to make my way to the kitchen via the chair room.

Turning right at the bottom of the stairs and entering the chair room - Playstation room, the crazy man room, the room where she had died - I saw the source of the darkness. The humming had followed me from that once closed door, now open. Countless fat flies blacked out the panel windows, buzzing and crawling, but never flying.

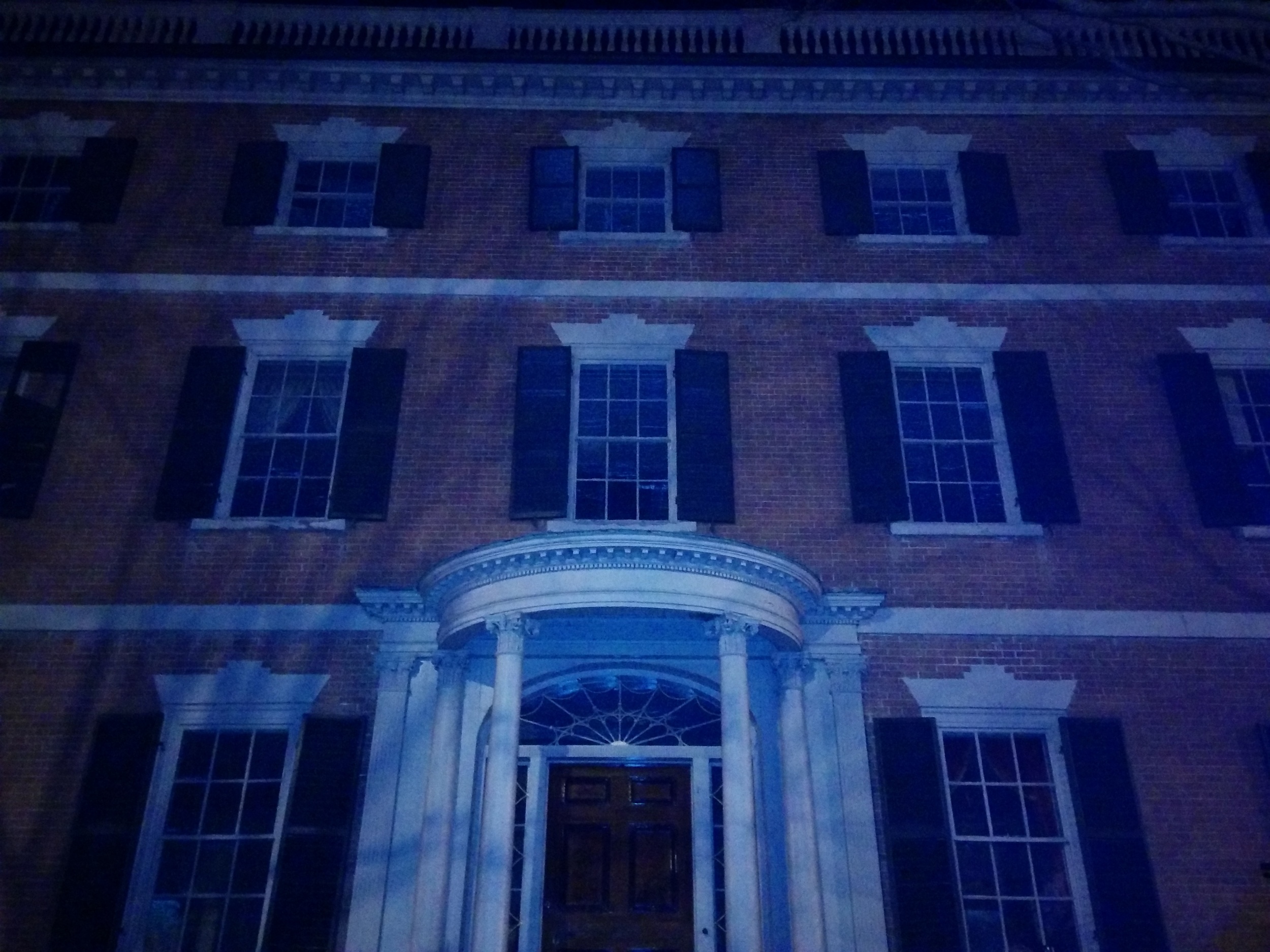

In Salem, Massachusetts, you aren’t allowed in the cemetery after dark. I expect that the same is true in most places, but given that the small New England city has become famous around the world for truly morbid reasons, the law here seems more appropriate, almost campy. This is where the witches were killed.

It is because of this law that the Salem Night Tour begins in a parking lot. My partner Emma and I, along with a Bostonian couple, follow Dominic, our young guide, to an empty gravel lot and he apologizes. As a tourism industry worker in one of America's most horrific destinations, he must understand better than anyone else how much his guests are hoping for a chance to walk on some corpses.

He’s sorry about the law. We won’t be able to enter any graveyards and that’s why we are standing on this parking lot instead of in a field of headstones. In Salem, grave markers are made of slate, meaning that its corpse lots (the last place Salemites will ever park) are the thin kind that don’t weather in the acidic New England rain and remind you of Halloween decorations. We’ll have to look on from a distance but that doesn’t mean we won’t be treading on the dead.

Our tour begins on a parking lot because it was a graveyard. We stand six (ish) feet over the dead who were buried next to a now haunted Episcopal church, their headstones moved into the basement and to the opposite side, but their corpses still resting. The showmanship of Dominic's reveal is pretty deft - especially considering our guide is wearing only a red lifeguard’s hoody with the sleeves rolled up in one degree weather - but the very act of standing on unmarked graves produces horror all its own.

A grave consists of two essential parts: a body and a marker. When the two become separated into a headstone and an unseen subterranean corpse, an unsettling semiotic transformation occurs. Graves are in graveyards, but headstones can be moved in the name of progress or politics and the dead may lie anywhere you can dig a hole.

A grave is a security blanket. We bury a body, mark its place and tell ourselves that dead people are only where we want them to be. It’s how we build a barrier between ourselves and the most incomprehensible of all thoughts: that one day we will no longer exist. Out of an anxiety born from the unknown experience (or un-experience) of death, we let the dead keep their labels. In this place, a body with this name that did things from this time to that time, is laid to rest.

All human comforts are contextual because with the absence of a reference point we can’t know anything. Alive, we claim death as our own, in death we are taken from the void by our survivors and made into a grave: a story that comforts everyone who will eventually join you.

Markers without bodies outside of St. Peter's Episcopal Church in Salem, MA.

Because context is controlled by the living storytellers, a death can mean something, but that meaning can change. This is true of all kinds of loss and all kinds of stories. Without context, we are nothing, on nothing, in nothing.

The power of context is formidable, and Salem is an excellent example of how re-framing the story of death can become political, and high-mindedly human. Emma put it perfectly when we first decided that we would spend our Easter Sunday in Salem: “The witches are taking back the night.”

Twenty women were executed in Salem during what Dominic calls “the Witchcraft Hysteria.” Those 20 women were among the 200 tried by puritan New Englanders, a process that saw them crammed into a windowless building - known officially as the Witch Dungeon - with a cellar that would flood in the spring. The women were imprisoned in coffin cells, which are long wooden boxes with bars instead of casket lids. They were left standing and defecating into frigid spring flood water.

The horrors of the Salem witch trials are poignant because witches are imaginary. And yet, paradoxically, they aren’t. Though the women in the dungeon and hanging from the trees in the 1600’s were wrongly (and sometimes maliciously) accused of signing a deal with the devil, Salem goes a step further than claiming their innocence. The city has embraced the image of the witch so much as to say, “Look, even if you were a witch, you didn’t deserve to die. Witches rule, puritans drool.”

The old Salem prison is now used as luxury housing, unlike the adjacent Witch Dungeon that was re-purposed as a haunted workplace.

Without context, my visit with Emma to Salem won’t seem magical, but the things we experienced carried with them an air of the sublime. Three key details will help frame the story:

First, we went to Salem on Easter because its reputation as a place for witches lead us to believe Christian holidays wouldn’t equate to closed stores.

Second, Emma’s bag had been stolen on our arrival to Boston, containing (in addition to thousands of dollars worth of property) her phone. My phone was blocking my data roaming, so our information resources were limited.

Third, we had trouble finding a Boston microbrewery and were pretty disappointed that our weekend trip would not involve craft beer tasting, which is somewhat of a travel tradition for us.

We arrived in Salem via the commuter rail at 5PM and it was empty. Aside from the (maybe) 20 other people who trained-in with us and quickly dispersed, it was just us. The campy occult shops we’d researched online were closed, leaving us in the cold on Salem’s main drag with three hours to kill and only one visibly open door: one leading to a real-deal, sans irony witch depot.

Inside, things were quiet and two warlocks patiently tended to their business while we browsed. If you’ve ever been to a mystic’s shop, you’ll know the drill: lots of herbal scents, working altars, library voices. We purchased a good intention (local herbs, oils and flowers meant to foster a specific state of being) for our pagan friend back home in Toronto, and the magic men sincerely but quietly wished us a pleasant stay.

Immediately upon exiting the store, our luck changed. We needed to find the meeting spot for the Salem Night Tour, found another open door, and were greeted by the organizer who also happened to be a paranormal investigator named Crash, who's appeared on Ghost Hunters International. The tour is run out of his Harry Potter shop and he was waiting for us. Because we were early, and hungry, and a bit shaken by the intensity of our encounter with Crash the Harry Potter fan, we exited and set about looking for food.

Two aimless right hand turns later we found ourselves in front of a Salem craft brewery.

Given the context, it is still difficult to explain these events with enough gravity. In the end, these doors were all open, just hidden from us at first. That we easily found the only open stores in Salem on Easter Sunday is barely a coincidence.

We set to framing our events immediately as soon as our luck turned, because we were dealing with the difficulty of losing Emma’s things and didn’t want to bear the responsibility of blaming ourselves for a lonely eventless evening in a small New England city. We felt the energy switch when, after thinking we were all wrong about Salem, it turned out we were so fucking right.

Giving ourselves over to the present, through disappointment, mild trauma and the fear of regret, allowed us to find the occulted doors of Salem, and they managed to lead us exactly where we wanted to be. The coincidence of that is too difficult to comprehend, so we layer a narrative on it. Reframing, context, the blessing of two warlocks - whatever we want to call it, it’s just something we tell ourselves instead of admitting we’re afraid of what we just don’t know.

The Salem Beer Works reclaims witchiness with horror camp and great brews.

Dominic tells us about the skeptic, who was exiled from Salem prior to the hysteria only to return, dig up a prominent corpse, drag it through the streets and then hold a gun to its head demanding he be reinstated as a citizen. He tells us about the dungeon, the Apocalyptic Salem curse and the time Houdini sprung three convicts from the local jail house during a high profile escape attempt. The Parker Brothers are Salemites and, in addition to making Ouija, they based Clue on a real life candlestick murder. Dominic shows us the Clue house.

Salem is the site of North America’s only execution by pressing. Giles Corey, who’d deflected witchcraft charges by having his wives tried for witchcraft ran out of human shields, found himself underneath a large church door as the townsfolk piled stones on top of him. It took three days for Giles Corey to die, and he is known for these final pleading words: “More weight.”

I ask Dominic what the trigger was for the trials. He says he doesn’t normally talk about that because it’s a deep question and most people have the preconception that a psychedelic contaminant had entered the town’s wheat source. While that may have been the catalyst, the short answer is really simple: fear. A woman had been tortured into confessing that a dark man had visited her and made her sign her name in his dark book. She said that seven other women had signed it, and the hunt began.

We pass another tour while Dominic finishes this story. Their guide is dressed like Jack the Ripper, lecturing his poor subjects about Dracula of all things, and I see the dark side of all of this. Dominic’s style is respectful and enthusiastic, for some people the symbols of horror are all lumped into one spooky category. A vampire, a witch, a zombie, a ghost - fiction or history - some people just want their stories to entertain.

Our second to last stop on the tour is not shown to every group Dominic walks around Salem, but I think he sees Emma and I nerding out and knows we’d appreciate the symbol. Six trees grow in a grassy lot with a broken wall at the end. This is the official memorial to the 20 women and five men executed for witchcraft. On the other side of the breach’s stone fence rests the man who tried them.

The idea was that their judge would look upon this memorial for all eternity, but Dominic says his grave actually faces the opposite direction.

Dominic says that the women recognized by the witchcraft memorial were never given a Christian burial. They were hung by the neck until dead on top of a hill, cut from the gallows and rolled down into a mass resting place.

This is not that gallows hill. The witches of Salem are remembered on a lot that was available in 1992, the 300 year anniversary of the hysteria. He tells us to look down, where we see quotes from the dead, engraved in the ground, one of them unceremoniously cut off by a stone bench: “I am not a wit-”

“This represents the fact that these women were not listened to,” he kicks dirt on some letters. “People walk over them without noticing.”

As we make our way to the Clue house and then onward to our Boston hotel, the massive full pink moon creeps above the horizon, peaking out from behind a graveyard, making the tombstones into silhouettes. It is a perfect image: a symbol made of lost lives, whose names I will never know, and who I will one day join, out of context; a pacifier for the living who just don’t want to be scared anymore.

For historical record: it was Colonel Mustard, in the bedroom, with the candlestick.