The New Invasion

Sorry Bela, we think you're cool now.

Dracula used to be scary because Bram Stoker’s audience was scared of immigrants. The strange man from a foreign land with an aversion to the religious icons of England moved in down the road and was out to steal everybody’s girlfriends. He would turn them into vampires, and back then people didn’t want to do dance the Monster Jerk, they wanted to live their proper lives without sucking blood and sleeping in coffins.

Well, times have changed. Not only have vampires become less scary, they have become cool. We aren’t scared of immigrants with big teeth that can grant us eternal life in undeath, we’re obsessed with them. We want to learn their traditions and be brought into their dark family. From Anne Rice’s vampire stuff, straight through the wrongly maligned romance of Twilight, up to the fantastic mockumentary What We Do in the Shadows, we have come to see the vampire as romantic, sympathetic and ultimately desirable.

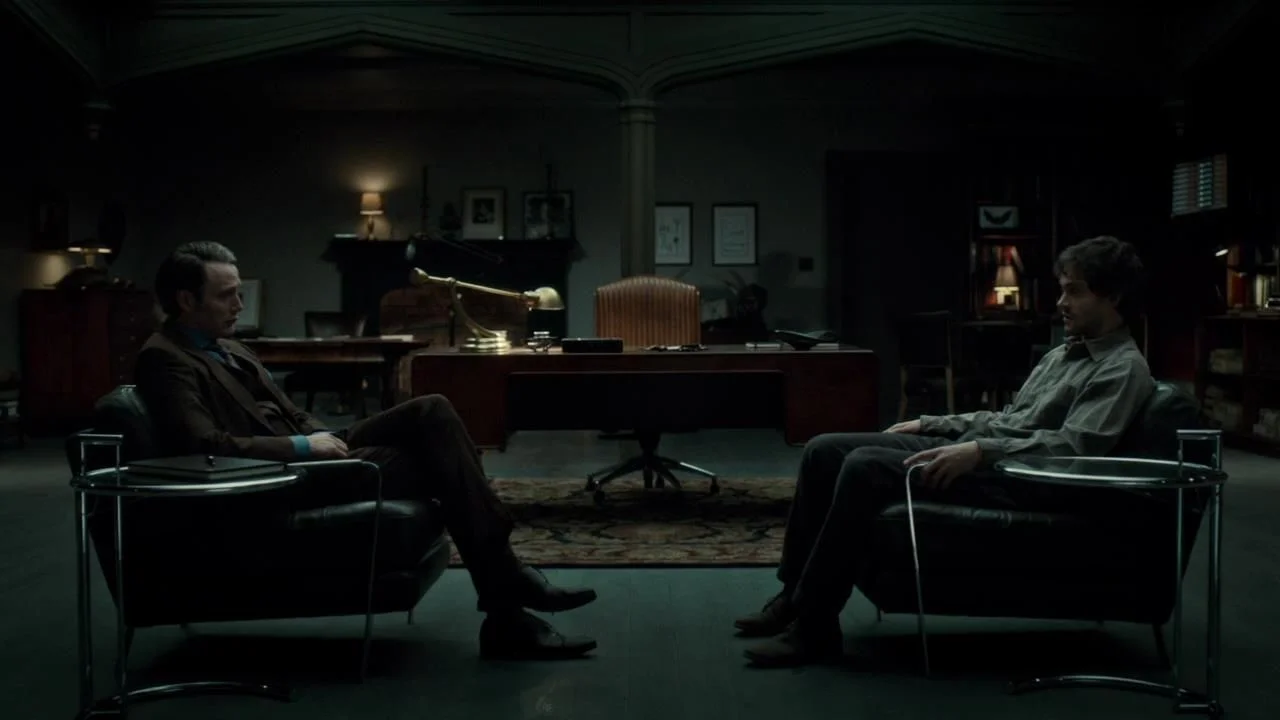

Even modern adaptations of the Dracula character, like Bryan Fuller’s masterful Hannibal, have trouble making the central monster truly horrific. At best, the horror of Draconian invasion fiction brings us on a journey to discovering that we have monsters inside of ourselves. Either we kill the strange being because of our own terrible ignorance or we abandon our sense of original identity and find ourselves wanting to be corrupted. We either love the monster like Will Graham, or we become it like Francis Dolarhyde.

You're right there! Stake the blood sucker!

But, despite our sympathy for the vampire, the tradition of invasion still scares today. In fact, I would argue it’s as popular and horrific as it has ever been, through it has changed to reflect contemporary fears. The modern invader isn’t a vampire or Lithuanian cannibal psychiatrist, it is an eldritch horror that brings with it the apocalypse.

The world is turning against us. We are mere degrees away from a runaway greenhouse effect that will turn our oceans to acid and our bones to charcoal. Global warming is the great modern threat, and while it is a byproduct of human activity, to the average individual who can only read about it and worry as they choose to walk to work instead of drive, it feels like a strange invasion. The great Nyarlathotep has emerged from slumber and a weird autumn has descended upon us.

Climatological horror occupies the grey area between human carnage (extreme horror) and cosmic insignificance (the great true horror). Climate is something we can experience through weather, but it is completely unhuman. In contemporary fiction, it is the tentacled monstrosity we worship as a god or the awful dreamland that’s replaced the park across the street where the thing you used to call “up” is a whole new direction (or is it a colour?) all together.

The best examples of the new invasion are in literature and games. Magic: the Gathering is currently exploring the theme of a climatological violation through its trademark environmental storytelling. In the current story arc, lovecraftian abominations known as Eldrazi are devouring the very life from a plane of existence. Representing this, the game’s token land cards are being supplemented with new types. The traditional islands, plains, mountains, swamps and forests now share space with wastes.

I don't have anything funny to type here because I take Magic cards very seriously.

Jeff VanderMeer’s Area X trilogy (which is a favourite topic of mine on this blog) takes away the tentacles and just presents an unknowable climatological invader. Inspired by the author’s visit to a national park, the titular area is simply a natural space that is hostile to humans. Area X annihilates humanity by transforming it into other life. The origin of the area is implied to be extraterrestrial, and the behavior of it is invasive, sending uncanny human-like emissaries into uncorrupted land as its borders annex more and more of our home.

The new invasion is one that makes us confront our fragile nature as a species. The visitors in these scenarios aren’t motivated out of malice, but rather they are indifferent to us, changing our environment to suit themselves so that we are incompatible with its new chemistry. A wasteland is still a land, and as it spreads with the progress of of the new invasion narrative the world will remain a world, but it will be a world without us.