The Silence Of The Lambs: You Don't Want Hannibal Lecter Inside Your Head

Since 34 episodes (and counting) of Hannibal are not enough to sate my bloodlust, I've been indulging in other pop culture iterations of the Hanniverse. Besides spending an inordinate amount of time on Archive Of Our Own and rereading parts of Thomas Harris's original novels, I've also revisited Manhunter as well as The Silence Of The Lambs.

In 1991, director Jonathan Demme wasn't considered a horror film director. Neither the screenwriter (Ted Tally) nor the cinematographer (Tak Fujimoto) were known for their horror bona fides, either.

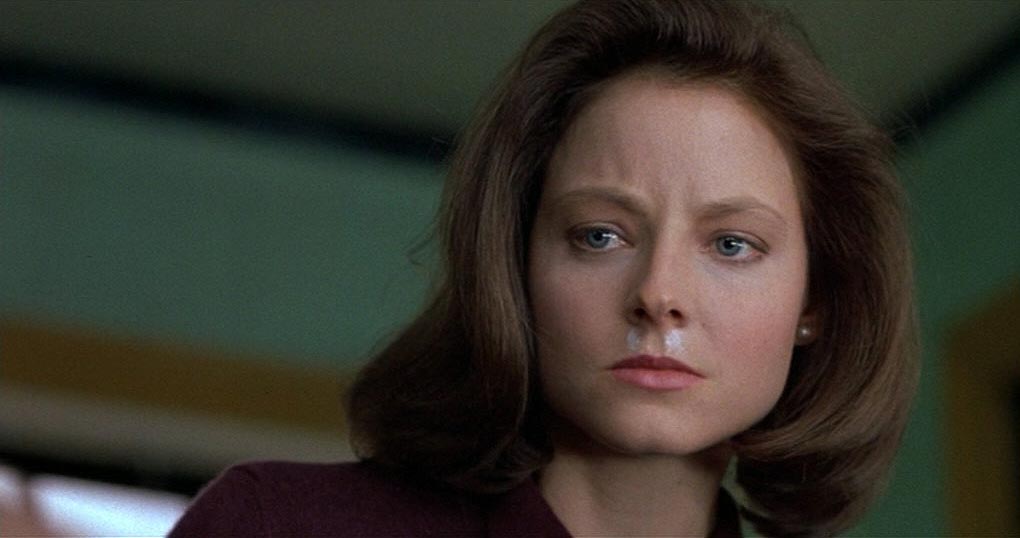

Jodie Foster's passion for the role seemed to place her as the ideal cinematic version of Clarice Starling, though she was not considered a horror movie actress. Even though Anthony Hopkins was chosen because of his work in The Elephant Man, anyone who saw his role in Magic knew that he could play creepy as well as, if not better, than anyone.

On IMDB, The Silence Of The Lambs is listed as "Drama, Mystery, Thriller" and while it does contain elements of all three, it's considered a horror film by many. Still, it may have been the other categorizations that allowed it to dominate the Academy Awards, with wins for Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, and Adapted Screenplay.

In the ensuing years, we've seen so many ludicrous spoofs of Hopkins as Lecter, that his portrayal of Hannibal the Cannibal has lost a lot of its luster. Like a lot of things in pop culture, people remember the imitators, not the originators, and judge the latter by the quality of the former, an unfortunate mistake.

When I saw Silence in theaters in 1991, admittedly, I was a horror newbie, but I found it terrifying. I wondered if it would still hold up after so many years and seeing so many more horror films. The answer is yes.

Composer Howard Shore, although he might be more familiar to younger viewers for his work on The Lord of the Rings films, had a history of scoring horror films: by 1991, he'd already worked on five David Cronenberg films. Part of what makes Silence work as a horror film is the score. It's suspenseful and emotional without being maudlin or clichéd.

Unlike Manhunter - the novel and the film - by Silence, we have already been introduced, albeit briefly, to Hannibal Lecter, so we think we know what to expect. Here we meet Clarice Starling for the first time and Demme wisely piggybacks off of Harris's already well-written character by allowing us to truly see things through Clarice's eyes.

It's Foster's steely yet sympathetic portrayal of Clarice that allows Hopkins's Lecter to be that much more menacing and the film as a whole to be utterly frightening. The F word itself is never used, but there are several allusions made to Starling's feminism: she reminds Dr. Chilton that UVA isn't a charm school and calls Jack Crawford out on his "Clarice, the men are talking" speech at the West Virginia morgue, in addition to brushing off Lecter's pointed sexual questions with a "That doesn't interest me and, frankly, it's the sort of thing that Miggs would say."

Despite her seemingly tough exterior, when she first encounters Hannibal, she's clearly daunted, and who wouldn't be? He's kept in a room that looks like a dungeon and she gets a slew of warnings from both Chilton and Crawford about not engaging with him. The buildup doesn't detract from the film's eventual reveal. In his cell, Hopkins looks akin to Boris Karloff's Mummy, but instead of dead, soulless eyes, his are bright blue and penetrating, extracting your most secret thoughts and fears. Hopkins's vaguely amused face and unblinking, wide eyes are truly unnerving.

Buffalo Bill a.k.a Jame Gumb, while also monstrous, is a different kind of bad guy, albeit one into whom Lecter has quite a bit of insight. When we see Gumb struggling with a broken arm and a couch outside of a windowless van, we know that it's not going to end well for poor Catherine Martin. His viciousness is further demonstrated when we see the waterlogged corpse of his most recently discovered victim displayed in West Virginia. The reactions of the men present show their obvious terror and disgust, but Starling exudes pure empathy. It's that quality which makes our own eventual view of the body that much more horrific. She is more than a just a victim, and Clarice bestows a dignity and human quality upon her, much like the one Senator Martin hoped to convey for her daughter through her televised plea to Buffalo Bill.

It isn't until later in Silence that we see Hannibal Lecter in predator mode and by then, we've almost become accustomed to his quirks. (By then, we've also witnessed the "it rubs the lotion on its skin" scene.) The need to have over a dozen cops creeping through a building with guns drawn might seem like overkill, but when Lecter savagely murders Sergeant Pembry and displays Lieutenant Boyle's corpse we are reminded that he isn't some quirky, demanding college professor, but a genuine, real-life monster.

Although Lecter is now on the loose, Clarice must focus on Gumb, and in the end she is the one who must face him. Her terror in his dark basement is palpable, with his night vision POV foreshadowing the aesthetic most of the found footage canon. Blinded and beyond fear, Starling is both completely out of yet totally within her element. She takes out Gumb like a pro, despite trembling the entire time, and it's a beautiful, heroic scene, sort of like Rachel McAdams's Ani Bezzerides in this season's True Detective shootout sequence, minus all the swearing.

By the time Lecter calls Clarice at her graduation party, she's already dismissed the idea that he would harm her. We see him slowly stalking Chilton, but only Chilton's grandmother could have sympathy for him at this point in the film. Clarice Starling shares something with Hannibal Lecter, and although she isn't a murderous psychopathic cannibal, that's enough to drive home the point that the monster walks among us.