Missing Pieces and Missing Pages: More On “Twin Peaks”

Much of the Twin Peaks universe deals in liminal spaces, despite the stark contrast of that black and white tiled flooring.

Read More

Much of the Twin Peaks universe deals in liminal spaces, despite the stark contrast of that black and white tiled flooring.

Read More

Swiggity swag Cronenstag.

This past week's installment of Hannibal, "Primavera," featured one of the more revolting scenes of the show (which is saying something). During one of Will Graham's empathing episodes, a skinned, dismembered, reconfigured corpse comes to life, sprouts hooves and antlers, and moves menacingly towards him.

Show creator Bryan Fuller dubbed the creation "Stagenstein," while production sketches for the show called it "Stumpman." (I'm partial to my own term, "Cronenstag.") This concoction is more grotesque than Mason Verger eating parts of his own face in Season Two's "Tome-wan." I remained fascinated and could not look away, even rewatching animated GIFs of the Cronenstag on Tumblr.

I've talked before about "the uncanny," in which things are both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. Somehow Cronenstag seemed worse to me. On the one hand it was a wet, fleshy creature that moved realistically. On the other hand, I know in my gut that it isn't real. So why the disgust and fear?

In many ways, this scene reminded me of the film Splice. (Vincenzo Natali, who wrote and directed Splice, also directed "Primavera.") The movie is one of the best examples of that Mystery Science Theater 3000 cliché, "he tampered in God's domain."

Two scientists (Elsa and Clive) develop animal hybrids for a genetic research company. Explicitly prevented by the company from adding human DNA into the mix, they conduct their human/animal hybrid genetic research in secret, eventually giving birth to a creature they refer to as "Dren." Dren is decidedly creepy and looks not totally unlike Hannibal's Cronenstag, with her spidery limbs and hoof-like feet.

Again, watching Splice I know that Dren is a cinematic creation and thus unreal. Still, Splice is one of the most disturbing and unpleasant films I've seen in recent memory precisely because it's so obviously unreal but could very well exist. As Natali noted in an interview on the film: "The centerpiece of the movie is a creature which goes through a dramatic evolutionary process. The goal is to create something shocking but also very subtle and completely believable."

Natali has explained in several interviews that the idea of Splice came from his encounter with the Vacanti mouse. In this experiment, scientists seeded "cow cartilage cells into a biodegradable ear-shaped mold" and then implanted it "under the skin of the mouse." (As an odd side note, the "nude mouse" on which the structure was grown is not a genetic experiment, but a spontaneous genetic mutation.) Are we repulsed by these images because we don't want to accept that such genetic experiments could actually be real? After all, the advent of cinematic technology has developed hand in hand with scientific technology; what filmmakers can create visually may not be so far removed from what scientists have created in labs.

Dren isn't the only creepy thing in Splice. Elsa and Clive also develop a pair of seemingly amorphous blobs named Fred and Ginger. These critters have been copyrighted and will be used to create livestock feed (an ethical quagmire in its own right). Fred and Ginger, like Dren, resemble what an article on sculptor Patricia Piccinini refers to as "parahuman." "Piccinini's parahuman beings are both uncannily real and somewhat disturbing. Certain people have a hard time with these works or find them so disturbing they can't stay near them."

Parahuman creatures like Cronenstag, Dren, or Fred and Ginger all recall what bioconservative scientist Leon Kass has called the "wisdom of repugnance." From Wikipedia: "In all cases, it expresses the view that one's 'gut reaction' might justify objecting to some practice even in the absence of a persuasive rational case against that practice." Since the "wisdom of repugnance" can also be used to justify prejudice against others on the basis of race, sexual orientation, disability, and a host of other factors, it's a problematic concept that has been the subject of much criticism. It can be argued that such prejudices reveal more about the repugnant qualities of the person who is objecting to another entity, i.e., that he is himself racist, sexist, or ableist.

In the case of Splice and the Cronenstag at least, repugnance is still a real reaction to something seemingly unreal. It begs the question: at what point does fascination veer into disgust or disgust into fascination? That's the precise kind of liminal space that both Splice and the Cronenstag occupy. It's a question whose answer can't be predicted, and that's scary.

Many film fans and filmmakers have recently expressed a desire to go back to the basics, aesthetically speaking, insisting that what you don't see in a horror film is scarier than anything conjured through CGI. They argue that smaller budget films are often more effective than tentpoles because financial restrictions force the filmmakers to be creative when devising ways to provoke an audience into fear.

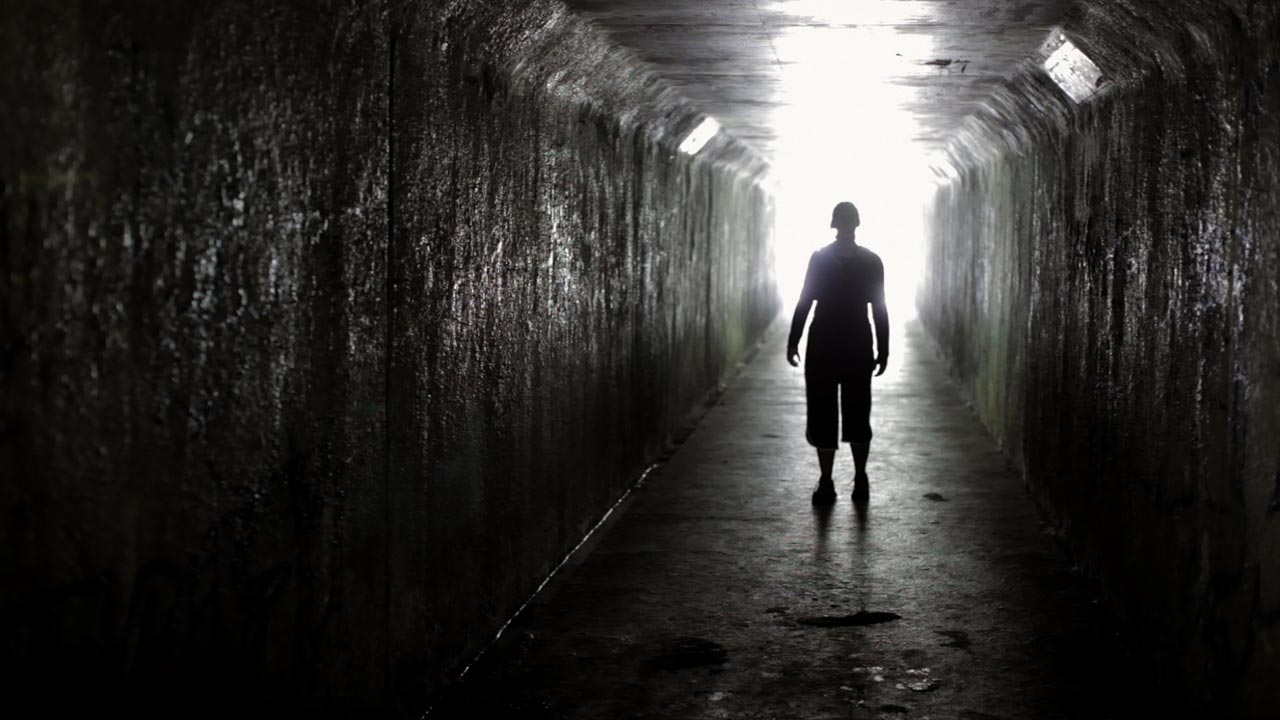

A beautiful example of this theory in practice is Mike Flanagan's 2011 film Absentia. It treads some of the same ground as Flanagan's more recent Oculus, in which a family is tormented over the years by a haunted mirror. In Absentia, the object in question is a tunnel connecting a Southern California subdivision to a nearby park.

Tricia's husband Daniel vanished seven years ago. No body was found, and after much anguish, she decides to have him declared dead "in absentia" for both legal and personal reasons. Her sister, Callie, a former runaway and drug addict, visits Tricia to help with the process of moving on and moving out of her apartment to begin again. Tricia his also pregnant, and offers no clues as to the identity of her unborn child's father, but she has embarked on a tentative relationship with Ryan, the cop in charge of Daniel's missing persons case.

Just as things seem to be progressing in a positive direction, Daniel shows up, both physically and psychically damaged, with only vague, nonsensical ideas of where he's been for the better part of a decade.

So much of Absentia's frightening aura comes from unreliable narrators: Tricia because she has lucid dreams of a black-eyed, enraged Daniel; Callie because, although she claims to be sober, she's still surreptitiously using drugs (though we don't see her in the act); Daniel because he speaks of a thing in the walls that's trying to get him.

When awful things start taking place in Absentia, we don't actually see them, only hints of them. Sounds and movements out of the corner of the eye; people who appear out of the shadows but aren't really there; a homeless man in a tunnel, begging for help and raving about nameless creatures. Such occurrences could easily be explained away.

There are a lot of typical problems in Absentia: flyers for missing people (including Daniel) and pets are pasted on telephone poles and there have been a series of petty burglaries in the neighborhood. We see these things so often they barely register with us anymore. Then there are the more personally upsetting, but still commonplace misfortunes: unpaid bills, legal paperwork, troubled marriages, broken families, single motherhood and addiction. Finally, there are fantastical issues that plague the characters: the alleged existence of a city underneath the ground, where humans are kidnapped by a monster with skin like a silverfish.

In Absentia, all of these events are connected. Furthermore, the gravity of these various tragedies shifts from banal to otherworldly and back again before the characters-or indeed the audience members-are aware that such a shift is taking place. Trying to explain it to someone who can't or won't understand - much like Callie does with Tricia - is met with disbelief. "It's easier to embrace a nightmare," says Tricia, "than to accept how stupid - how simple - reality is sometimes."

But what if the answer is both a nightmare and reality? Much like the tunnel that connects the characters to the horrible thing that holds sway over them, Absentia occupies that liminal space between reality and unreality. Was the silverfish crawling in the sink just a bug or a harbinger of something worse? Is Daniel a paranoid schizophrenic? Did Tricia imagine his appearance or was he truly there? Was Tricia spirited away by the thing in the tunnel or did she cut herself off from the grid to start her life over again?

There's a scene in the film where Tricia and Callie are turning out the lights to go to bed, and Callie hears a noise. The camera cuts to a shot of Tricia, staring into the black nothingness of her living room. But instead of a void, there's a monster in there that literally takes her away. We never see the monster, but Tricia's absence is as palpable as its presence. Later Tricia scrawls, "beware the things underneath" on a note she leaves for Ryan.

This liminality is what makes Absentia genuinely terrifying. It feels like the events in this film could happen to anyone, even us. If that happened, then who would believe us? We are all unreliable narrators of our own lives in a way; our experiences and prejudices color our perceptions of what we see. We can never totally be sure of our own objectivity and that sure scares the hell out of me.