True Detective Horror Diary: The Forest of Leng

In the first True Detective Horror Diary, presented in partnership with That Shelf, we examine the big Lovecraft reference from the season three premiere: the Forest of Leng.

Read More

In the first True Detective Horror Diary, presented in partnership with That Shelf, we examine the big Lovecraft reference from the season three premiere: the Forest of Leng.

Read More

If it truly is the end of 'The X-Files,' then we could not have asked for a more perfect season.

Read More

Everyone is wondering what Scully whispers in Mulder's ear in that church. But will we ever find out?

Read More

"Ghouli" is a bittersweet episode of 'The X-Files' that's packed with narrative and a little bit of levity, thanks to Mulder.

Read More

“The Lost Art of Forehead Sweat” proves that 'The X-Files' is more relevant than ever and will likely go down as one of the series' top five episodes.

Read More

Making sense of 'The X-Files' in a post-Trump world.

Read More

Why doesn't 'Mr. Mercedes' appear on more "Best TV of 2017" lists?

Read More

“Be on guard! Be alert! You do not know when that time will come.” Mark 13.33

Read More

Does being a fan of genre fiction like The Handmaid's Tale make one less of a "true" feminist?

Read More

After many decades of being relegated to VHS tapes and YouTube uploads, Ghostwatch is now finally available to watch, but does it hold up?

Read More

'The Path' trafficks in deception and denial of the void that lies beyond, a void that is often reflected in our innermost selves.

Read More

Well-crafted characters make the scary situations on Fox's The Exorcist that much more frightening and compelling.

Read More

Come for Hugh Dancy being creepy; stay on The Path for Hugh Dancy being even creepier.

Read More

The dream of the '90s is alive in The X-Files. Or is it?

Read More

What would happen if Fox Mulder met Will Graham, or at least tried to think like he does?

Read More

Alana Bloom: ... what do you think one of Will's strongest drives is?

Jack Crawford: Fear. Will Graham deals with huge amounts of fear. It comes with his imagination.

Alana Bloom: It's the price of imagination.

The mythology of Will Graham, as created by Thomas Harris, was always a mystery. Reading Red Dragon, we were allowed glimpses into his psyche, his internal thoughts, but many of those thoughts were borrowed.

Will is described as an eideteker, an empath, someone whose mirror neurons never melted away after childhood. When he seeks out killers, they come knocking at his door. Yet unlike vampires, they let themselves into his mind without his permission.

When Hannibal the TV series begins, we learn about Will through the same methods established by Harris initially: his serial killer profiling. Of course, the film versions of Will - in Manhunter and Red Dragon - provided a visual aspect to what had only been captured in words before, but Bryan Fuller's vision of Will's unique gift is different. It is more vivid and bloody, more beautiful and terrible.

It isn't long in the series before Will meets the ultimate in beauty and terror, Hannibal Lecter. Harris created Hannibal, too, but with the Hannibal series, Fuller and company filled in the gaps that Harris didn't talk about in his novels, the time between Hannibal's childhood and when he encounters Will Graham. We, along with Will, eventually realize that those gaps are more like chasms, or the gaping maw of hell.

Hannibal as presented in Manhunter was a terrifying creation. Brian Cox did more with a scant few minutes of screen time, a clipped accent, and dead, black eyes than three movies' worth of Anthony Hopkins. That's the Hannibal that Bryan Fuller wanted to exploit, and to do so, he found the best version of Hannibal Lecter yet, Mads Mikkelsen, whose wolfish eyes and predatory smirk evoke a sense of unease and discord that none of the cinematic interpretations had quite managed to address.

As the latest incarnation of Harris's characters, Hannibal had the luxury of being able to use shorthand to convey backstory, personality traits, and motives, but instead of taking the easy route, the show adds baroque layers of complex psychology, references to literature and art, and deeply convoluted double entendres. This renders Hannibal 3.0 a wholly other creature.

Knowing he is a cannibal but seeing him portrayed as a classy aesthete and not actually seeing him kill, makes Hannibal Lecter as much of a mystery as Will Graham, who is portrayed by Hugh Dancy on the show as something of a trembling teacup (at least at first). When Hannibal's murderous nature reveals itself, it's in small doses. Although he tells Garrett Jacob Hobbs that the police are onto him in the first episode, Hannibal still comes across as more curious than outright nefarious. Hobbs seems frightening by comparison.

Bit by bit, we see what lurks underneath Hannibal's "person suit," as Bedelia Du Maurier calls it. He bashes Alana Bloom's head against a wall so she won't know what he's doing, in the first indication that he is capable of cold-blooded violence. When he cuts Dr. Sutcliffe's throat, we see this through Georgia Madchen's illness-compromised eyes, and his face is blurred. When he breaks Franklyn's neck, it's a matter of self-preservation not homicide.

What's more frightening are scenes of Hannibal looming over Bedelia as she tries to end their doctor/patient relationship and Hannibal suddenly appearing behind Beverly when she discovers his murder basement. It's a palpable threat that feels scarier than the act of killing itself.

Even when Will discovers that Hannibal is the Chesapeake Ripper, he's so wracked by his encephalitis that it feels more like exhausted outrage than terror. In betraying Will - hiding his medical diagnosis and framing him for the murders - he's committed premeditated murder against their friendship.

When he's exonerated for Hannibal's crimes, Will decides to publicly forgive Hannibal and resume the FBI-ordered therapy with him on his own accord, but it's a pretext to gaining Hannibal's trust and exposing him. This eventually leads to Will moving from empathizing to embracing, in this case, the dark side of his nature. Instead of just catching a killer, he kills one: Randall Tier. What has always fascinated Hannibal and attracted him to Will is his ability to exploit his empathy. Hannibal wants Will to become a killer in more than imagination; his most fervent desire is for Will to become a killer in reality.

Hannibal, hiding "behind the veil," is also besotted by Will's ability to see him as he truly is. The second and third seasons of the show further explore Hannibal's dedication to transforming Will and Will's commitment to Hannibal, one which feels more like an involuntary stay at a mental institution than a relationship entered into with clear eyes and a pure heart.

Both of these seasons explore the arc of Will pretending to be one thing, while acting another, much like Hannibal did throughout the first season. By this point, of course, Will has already echoed many of Hannibal's own words and has even begun to dress more like the doctor, exchanging his fly fishing jackets for tweed coats. This cat and mouse game continues throughout the second season, until neither the audience nor Will seem to know if he's sincere about his reciprocated feelings towards Hannibal or just playing the long con. This culminates in Will's betrayal of Hannibal, and Hannibal gutting Will and leaving him for dead.

Will survives and so does his relationship with Hannibal. That already thin line between the two doesn't disappear, but becomes a blood vessel that connects them both. It's terrifying: Will has looked into the abyss and not only has someone looked back at him - Hannibal - it's someone with his own face. Through its third season, the show upends the idea of a soul mate, or to borrow a term from fanfiction, a One True Pairing (OTP) by transfiguring it into something both terrible and beautiful. Will becomes something else, and so does Hannibal. Like Hannibal, we truly see Will for the first time, in a way that we never did with the previous cinematic interpretations.

Hannibal is Will's greatest weakness, and Will is Hannibal's. They aren't necessarily, as Aristophanes proposes in Plato's Symposium, two halves of one whole, they are as Jack Crawford states, "identically different." It's a kind of love that surpasses morality or even sexuality. Not only does Will embrace his darkest nature, he embraces his darkest self, in this case, Hannibal. He embraces him literally after they kill Dolarhyde together. For the first time, Hannibal has let someone see him - all of him - and not desired to kill the voyeur. He merely desires the voyeur.

There's a reason that relationships are described as "falling in love." It's the loss of control that people fear. At the end of Hannibal's third season, in "The Wrath of the Lamb," Will and Hannibal not only embrace each other, they fall - both literally and metaphorically - off of a cliff into an abyss.

The abyss that Will and Hannibal tumble into is one of love, murder, and the great unknown. What Will Graham always feared the most was becoming a killer; when he finally becomes one, he fears that he loves it - and Hannibal - too much to continue existing. What takes place next is purposely unclear, much like the nature of love itself. We don't see any bodies at the bottom of that cliff, but we do see two more place settings at Bedelia's table.

Thus the most beautiful and terrifying aspect of Hannibal - and the legacy of the show - will always remain that abyss, the inability to know, even when we think we do. This is its design, and its genius.

By the third episode of the first season of The X-Files, the series had already established Fox "Spooky" Mulder's obsession with extraterrestrial life and Dana Scully's skeptical nature. With "Squeeze" the show temporarily dispensed with the alien mythology and introduced its first, but certainly not its last, monster of the week in Eugene Victor Tooms.

Tooms is a mutant serial killer who kills in sounders of five (thanks Will Graham!) every 30 years, consuming the livers of his victims before hibernating inside a nest of newspapers and bile (yum). Mulder finds his elongated fingerprints at a murder scene and connects it to an X-File.

What's interesting about "Squeeze" is that Tooms is presented as an entity that is totally unique: he doesn't conform to any commonly known monster archetypes. An argument could be made that he is similar to a creature from Afghanistan known in folklore as Al-i Dil Kash, a "sinister female supernatural who has elastic limbs and can stretch out her arms to seize the heart of a sleeping bridegroom and thus kill him." One could also compare Tooms to Mr. Fantastic or Plastic Man, but more murderous.

Chris Carter was inspired to create the Tooms character after eating foie gras and contemplating the rumors surrounding Richard Ramirez a.k.a., the Night Stalker, who allegedly broke into his victims' windows without disturbing the dirt on their windowsills.

Yet, the way Tooms is presented is straight out of classic horror movies, namely the various incarnations of Dracula.

While Dracula could turn himself into mist to sneak under doors and through cracks in windows, Tooms physically alters himself, like a contortionist, to get into small spaces, like air vents. Like a vampire, Tooms hibernates until he needs sustenance, but instead of blood, he craves human livers. He doesn't sleep in a coffin, but it's no accident that his name is a homonym for the word "tombs." Before he kills his second victim, he's shown in semi-darkness, with only his eerie, glowing yellow eyes, quite similar to the iconic shot of Bela Lugosi in Tod Browning's Dracula from 1931. Later, when Mulder and Scully find his nest at 66 Exeter Street, he is again shown in mostly darkness, lit from underneath, with his creepy eyes highlighted.

Tooms is eventually caught when he attacks Scully, and although he isn't charged or convicted for any murders, going after a Federal agent is enough of a reason to incarcerate him for a while. The character proved so popular that he was brought back for episode 21 of the same season, "Tooms." In this episode, Tooms is up for parole. His therapist, Dr. Monte, feels sure that he'll be released. A physician also testifies that Tooms suffers from no "organic physiological dysfunction." When Mulder takes the stand and starts talking about genetic mutation and then claims that Tooms is responsible for murders going back into the early 20th century, he's quickly shut down and dismissed. And Tooms is released and goes back to his old job as a dogcatcher.

He's still dangerous, though, and perhaps worse, he's malevolent. It's not just that he needs livers to survive; like Dracula, he seems to enjoy stalking and killing his victims. He picks up a dead rat and tosses it into the back of his truck, but much like Gary Oldman in Francis Ford Coppola's 1992 version of Bram Stoker's Dracula, he can't help licking his fingers first.

Tooms ends up killing Dr. Monte, and Mulder knows that with this, his fifth victim, he'll be hibernating soon. Mulder keeps track of Tooms through some off-the-record surveillance, eventually following him back to 66 Exeter Street, which has now been converted into a shopping mall. Tooms tries to kill Mulder but he narrowly escapes. He and Scully manage to crush Tooms in an escalator, putting a suitably grisly end to one of the most grisly killers in The X-Files' nine-season history, and certainly one of the most genuinely frightening.

Note: The title for this piece comes from a prequel script that actor Doug Hutchinson, who played Tooms, wrote for The X-Files that was neither read by Chris Carter nor produced for the show.

While keeping up with my 201 Days of The X-Files viewing schedule, I re-watched one of the show's most iconic episodes, "Beyond The Sea." Besides being notable for yet another reference to Mulder's porn proclivities ("Last time you were that engrossed, it turned out you were reading the Adult Video News," Scully quips), it's a perfectly constructed episode that reveals cracks in Scully's scientific demeanor.

The episode opens with Scully saying goodbye to her mother and father after she's cooked them a Christmas Day meal. William Scully addresses his daughter with a gruff but affectionate "Goodnight, Starbuck" before he leaves. Later, Scully falls asleep on the couch and is awoken by her father sitting in a chair across from her. His lips are moving but no sound is coming out of his mouth. Startled, she addresses him but he doesn't respond. The phone rings and it's her mother, informing her that her father has just passed away from a massive coronary. When Scully looks back at the chair, her father is no longer there.

The case this time involves a death row inmate named Luther Lee Boggs, portrayed with scenery-chewing glee by Brad Dourif, in a nod to his role in The Exorcist III. Mulder's profile of the prolific serial killer is what put him in his current predicament, but when he was first sent to the gas chamber, there was a last-minute executive stay and his life was spared. Boggs asserts this experience sparked the flame of psychic abilities within him and he has contacted Mulder claiming to have vital information about a recent series of kidnappings and murders, hoping to avoid his rapidly approaching rescheduled execution.

Mulder thinks Boggs is just a con artist but he's more concerned that Scully is coming into the office after her father has just died. She assures him that she "needs to work" so he drops the subject. At her father's funeral, the jaunty strains of Bobby Darin's "Beyond The Sea" are heard, the song that was playing when Captain Scully's ship returned from the Cuban Blockade. It's difficult to swallow the lump in the throat we feel when a clearly bereft Scully tremulously questions her mother, "Was Dad at all proud of me?" All her mother will say is, "He was your father."

"I tore this off my New York Knicks t-shirt. It has nothing to do with the crime."

When they visit Boggs in prison, Mulder goads him into putting on a psychic revelations pageant, positive he's exposed him as a fraud. He leaves in disgust. As Scully packs up her files Boggs starts singing "Beyond The Sea" and she stops cold. Boggs fixes his eyes on her and asks, "Did you get my message, Starbuck?" Scully looks wounded. Outside, Mulder can tell something is wrong, but she just attributes it to "my father" before apologizing and leaving.

Scully discovers some of the things that Boggs said about the location of the kidnap victims were true when she does a little investigating of her own. Mulder becomes angry when she suggests that Boggs was right, warning her that she should only open herself up to "extreme possibilities" when they're the truth, insisting that Luther Boggs is "the greatest of lies." Mulder's explanation is that Boggs is working with someone on the outside and is an accomplice in the kidnappings and murders.

Still, Scully advocates for making a deal with Boggs, if only to get information to save the kidnap victims before they become murder victims. Another visit to Boggs results in more information and a warning about Mulder's blood on a white cross. When the FBI agents visit the docks Boggs told them about, they find Elizabeth, one of the victims, but they also spy a boat leaving the scene. A gunshot rings out and catches Mulder in the leg. Scully notices two white crossbeams nearby covered in Mulder's blood.

Mulder's theory about Boggs having an accomplice seems to be confirmed when Elizabeth identifies one Lucas Jackson Henry as her abductor and there is evidence that Boggs and Henry committed murders together before the former's incarceration. Furious, Scully revisits Boggs and spits venom: "No one will be able to stop me from being the one that will throw the switch and gas you out of this life for good, you son of a bitch!"

"I'll believe you... if you let... me talk to him."

Smooth-talking Boggs keeps seducing her. "I know who you want to talk to," he sneers, but insists he won't let Scully have her way until he gets a deal. She maintains that she doesn't believe him, but when she visits Mulder in the hospital she proposes there could be another explanation. Mulder tells her not to deal with Boggs, but Scully doesn't listen, visiting him yet again. He mentions the Blue Devil Brewery up by Morrisville.

As it turns out, that's exactly where Henry and the kidnap victims are. After a shootout and chase, Henry falls through some loose floor beams to his death. Scully notices a painting of a blue devil on the wall behind him and recalls Boggs warning her not to "follow Henry to the devil." She goes to thank Boggs for saving her but he suspects she still has "unfinished business," and begs her to come to his execution so she can "get her message."

But she doesn't. Instead, she visits Mulder in the hospital and tries to rationalize that Boggs might have gotten all the information he needed from her personnel file. "Dana," Mulder interrupts, "After all you've seen, after all the evidence, why can't you believe?"

SCULLY: I'm afraid. I'm afraid to believe.

MULDER: You couldn't face that fear? Even if it meant never knowing what your father wanted to tell you?

While "Conduit" showed that it was the fear of not knowing which drives Mulder, Scully presents a different side of the knowledge coin in "Beyond The Sea." From the beginning of the show, Scully has worn a small gold cross around her neck, indicating that she believes in something other than science, even though it has not been discussed up until this point. But how far does that belief go? And is it just faith in a God that keeps Scully going? Is the possibility of finding proof of something beyond science or even religion too frightening for her to accept?

In the last scene, Scully tells Mulder that she did know what her father wanted to tell her because, like her mother said, "He was my father." While "Beyond The Sea" purports to show Scully opening herself up to extreme possibilities, she ends up reverting to her closed-off views at the end. It seems to be Scully's faith that keeps her going, but it's faith in not believing. Mulder has faith in things he wants to believe, the intangible and abstract truth for which he so desperately searches. It will be a while before Scully can walk through those particular doors.

In preparation for the upcoming six-episode season of The X-Files in 2016, a rewatch of all nine seasons of the original series seemed like a timely idea, especially since I never finished the last two.

In the midst of all the "remember the '90s" nostalgia about clothing, cars, and how ridiculously youthful both David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson look, I realized something important: I finally get it.

It's not that I finally "get" why the show was such a big deal. I was a huge fan of The X-Files when it first aired in the early '90s. It was my pre-Hannibal Hannibal, with the same creepy aspects that I loved about The Twilight Zone and Twin Peaks, plus a dash of Unsolved Mysteries. In several cases, it actively frightened me ("The Host," "Hungry," and "Folie À Deux" immediately come to mind).

What finally makes sense to me is Fox Mulder's unwavering dedication to finding the truth that he insists is out there. Fear of the unknown is one of the most primal fears, but what about the fear of not knowing? That's the precise fear that drives Fox Mulder.

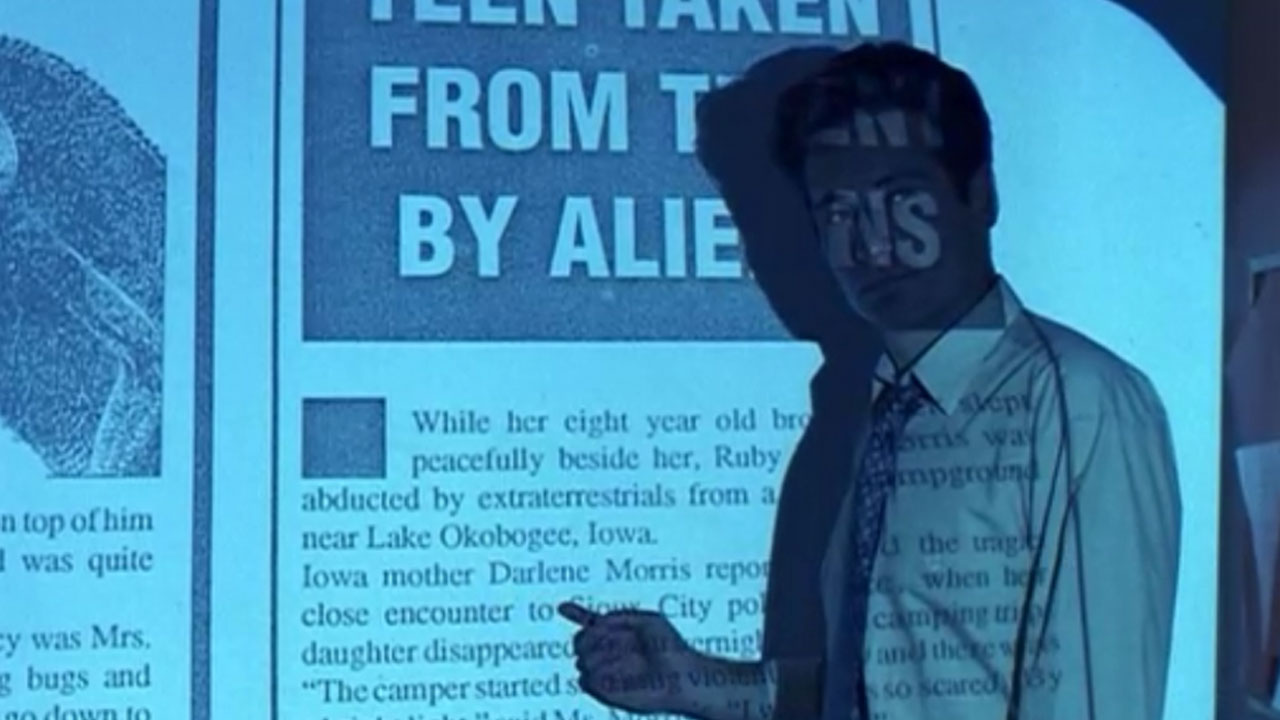

Episode S104, "Conduit," finds Mulder and Scully in Iowa, where Ruby Morris has disappeared in the middle of the night, during what her mother Darlene describes as a blinding flash of light. What makes the incident intriguing to Mulder is that this light fits in with several alien abduction stories he's uncovered in the X-Files themselves.

Scully, along with the audience, thinks that Mulder is drawn to this case because of its similarities to the events surrounding his own missing sister, Samantha, which he had revealed to her in the show's pilot episode. He denies this, insisting that Darlene's own past is the hook. When she was in Girl Scouts, Darlene, along with a few others, saw a UFO in the same Lake Ogobogee area where Ruby went missing. Mulder is convinced that those same aliens have come back for Darlene's daughter.

More is revealed during the course of this episode suggesting that perhaps Ruby was just a runaway teen in trouble. Darlene's younger child, Kevin, meanwhile, has become engrossed in writing down thousands of pages of binary code and like Carol Anne in Poltergeist, tells Mulder that the messages are coming from the TV.

Mulder is intent on finding out more from Kevin, but the NSA eventually shows up and starts ransacking the Morris home, taking Kevin in for questioning because some of the stuff he's been writing might be a threat to national security. After that, Darlene warns Mulder and Scully to back off. Scully tells Mulder that solving this case won't bring his sister back. He swears he's not giving up on Ruby until they find a body.

Not long afterward, Ruby reappears in the woods, confused, but seemingly unharmed. Mulder pleads with Darlene to be receptive to her daughter's memories of what actually happened. "She should be encouraged to tell her story," he says gently, "not to keep it inside, it's important that you let her." Darlene dismisses him, saying that Ruby can't remember anything. But Mulder persists, and we see for the first time what Scully has tried to get him to admit, and what the people who assigned Scully to the X-Files believe is Mulder's greatest weakness as well as his greatest strength: his desire to know.

"But she will remember one day, one way or another, even if it's only in dreams. And when she does, she's going to want to talk about it, she's going to need to talk about it."

It's then that I finally understood why Mulder spent so many years searching. Losing a family member to death is one thing. I lost two grandparents and a stepfather within the same year when I wasn't yet a teenager. That was awful. Having a sister vanish in front of you with no idea where she went, who took her, or what happened to her must be unbearable.

For those in search of missing family members, the fear conjured by simply not knowing must be agony. For Mulder, it has the added indignity of marking him forever as a fanatic and making authorities less likely to dig into what he suspects are the real reasons behind her disappearance.

"Conduit" ends with Scully listening to a tape of one of Mulder's therapy sessions, in which he's been hypnotized and asked to recall the events of that night. It's utterly heartbreaking and for the first time when watching this episode, I truly felt his fear. It's not a fear of the unknown or even a fear of the uncanny, but the fear of not knowing.

I thought: what if it was my own sister who'd disappeared in the middle of the night? What if no one believed me when I told them what I thought happened? What if I never truly found out? What if I never saw her again? Just thinking about that scares the hell out of me. Not long after that series of deaths when I was a child, my dog disappeared into the night, never to be seen again, either alive or dead. It was so traumatizing I didn't even write about it in my diary. In fact, I can barely remember it.

Even though Mulder remembers what happened that night, it's with a couple of caveats. His memories haven't helped him or his sister; the rest of his family has been torn apart.. He's become privy to the memories themselves, but separated from the act of remembering, something which would instill terror into anyone's heart.

Mulder's curiosity is both a blessing and a curse for him, but it's the fear at the core of that curiosity that makes "Conduit" a remarkable episode and proves that The X-Files still compelling after all these years.

Swiggity swag Cronenstag.

This past week's installment of Hannibal, "Primavera," featured one of the more revolting scenes of the show (which is saying something). During one of Will Graham's empathing episodes, a skinned, dismembered, reconfigured corpse comes to life, sprouts hooves and antlers, and moves menacingly towards him.

Show creator Bryan Fuller dubbed the creation "Stagenstein," while production sketches for the show called it "Stumpman." (I'm partial to my own term, "Cronenstag.") This concoction is more grotesque than Mason Verger eating parts of his own face in Season Two's "Tome-wan." I remained fascinated and could not look away, even rewatching animated GIFs of the Cronenstag on Tumblr.

I've talked before about "the uncanny," in which things are both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. Somehow Cronenstag seemed worse to me. On the one hand it was a wet, fleshy creature that moved realistically. On the other hand, I know in my gut that it isn't real. So why the disgust and fear?

In many ways, this scene reminded me of the film Splice. (Vincenzo Natali, who wrote and directed Splice, also directed "Primavera.") The movie is one of the best examples of that Mystery Science Theater 3000 cliché, "he tampered in God's domain."

Two scientists (Elsa and Clive) develop animal hybrids for a genetic research company. Explicitly prevented by the company from adding human DNA into the mix, they conduct their human/animal hybrid genetic research in secret, eventually giving birth to a creature they refer to as "Dren." Dren is decidedly creepy and looks not totally unlike Hannibal's Cronenstag, with her spidery limbs and hoof-like feet.

Again, watching Splice I know that Dren is a cinematic creation and thus unreal. Still, Splice is one of the most disturbing and unpleasant films I've seen in recent memory precisely because it's so obviously unreal but could very well exist. As Natali noted in an interview on the film: "The centerpiece of the movie is a creature which goes through a dramatic evolutionary process. The goal is to create something shocking but also very subtle and completely believable."

Natali has explained in several interviews that the idea of Splice came from his encounter with the Vacanti mouse. In this experiment, scientists seeded "cow cartilage cells into a biodegradable ear-shaped mold" and then implanted it "under the skin of the mouse." (As an odd side note, the "nude mouse" on which the structure was grown is not a genetic experiment, but a spontaneous genetic mutation.) Are we repulsed by these images because we don't want to accept that such genetic experiments could actually be real? After all, the advent of cinematic technology has developed hand in hand with scientific technology; what filmmakers can create visually may not be so far removed from what scientists have created in labs.

Dren isn't the only creepy thing in Splice. Elsa and Clive also develop a pair of seemingly amorphous blobs named Fred and Ginger. These critters have been copyrighted and will be used to create livestock feed (an ethical quagmire in its own right). Fred and Ginger, like Dren, resemble what an article on sculptor Patricia Piccinini refers to as "parahuman." "Piccinini's parahuman beings are both uncannily real and somewhat disturbing. Certain people have a hard time with these works or find them so disturbing they can't stay near them."

Parahuman creatures like Cronenstag, Dren, or Fred and Ginger all recall what bioconservative scientist Leon Kass has called the "wisdom of repugnance." From Wikipedia: "In all cases, it expresses the view that one's 'gut reaction' might justify objecting to some practice even in the absence of a persuasive rational case against that practice." Since the "wisdom of repugnance" can also be used to justify prejudice against others on the basis of race, sexual orientation, disability, and a host of other factors, it's a problematic concept that has been the subject of much criticism. It can be argued that such prejudices reveal more about the repugnant qualities of the person who is objecting to another entity, i.e., that he is himself racist, sexist, or ableist.

In the case of Splice and the Cronenstag at least, repugnance is still a real reaction to something seemingly unreal. It begs the question: at what point does fascination veer into disgust or disgust into fascination? That's the precise kind of liminal space that both Splice and the Cronenstag occupy. It's a question whose answer can't be predicted, and that's scary.