“A Monstrous Sacrifice:” ‘IT’ as American Folk Horror

Not only is the 2017 cinematic adaptation of Stephen King's 'IT' scary, it also deserves a place in the American Folk Horror canon.

Read More

Not only is the 2017 cinematic adaptation of Stephen King's 'IT' scary, it also deserves a place in the American Folk Horror canon.

Read More

Mulder and Scully, confronted with their own mortality, do the deed in one of the most poignant 'X-Files' episodes yet.

Read More

“Be on guard! Be alert! You do not know when that time will come.” Mark 13.33

Read More

The announcement that the Vanguard Programme will no longer be a part of the Toronto International Film Festival leaves a giant hole in my heart.

Read More

'The Path' trafficks in deception and denial of the void that lies beyond, a void that is often reflected in our innermost selves.

Read More

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s latest film, 'Creepy,' goes above and beyond what its title implies.

Read MoreJerry seems like a nice guy. He works at a bathtub factory in Milton and lives in the upstairs apartment of an old bowling alley with his two pets, Bosco (the boxer) and Mr. Whiskers (the yellow tabby cat). Jerry is kind of shy and awkward, but his therapist encourages him to participate in planning the annual office picnic. Jerry is also smitten with Fiona, the beautiful English woman who works with him, and hopes that he’ll be able to woo her with his humble charms.

The Voices begins like a sweet romantic comedy with a slightly dark undertone. As Jerry, Ryan Reynolds is less Green Lantern and more Clark Kent. We find out right away that he talks to Bosco and Mr. Whiskers and that they talk back. We figure he’s got some kind of schizophrenia, which is confirmed when he fudges the details about hearing voices and taking his meds. It doesn’t seem like that big of a deal until Fiona is revealed to be something of a self-centered creep and Jerry accidentally-on-purpose stabs her to death.

It’s a shocking scene in a movie that, up until that point, feels like a quirky art-house film. Director Marjane Satrapi and writer Michael R. Perry shift the tone of The Voices in an uncomfortable direction, one that almost feels like it was borrowed from another genre. It’s a stylistic gamble that actually pays off due to Ryan Reynolds’ sympathetic portrayal of Jerry and some straightforward talk about mental illness.

In her review of The Voices, The Spectator’s Deborah Ross doesn’t mince words about how much she “bitterly” resents having to watch the movie at all, describing it as “hateful” and “repellent” and singling out its tone shift for particular condemnation. I have to wonder if we saw the same movie. There are certainly horror films that seem to glorify the killer’s grisly acts or which revel in misogyny for misogyny’s sake (the recent remake of Maniac, for example), but The Voices doesn’t even show most of the crimes that Jerry commits. The majority of his murders take place off screen and he clearly, obviously, and repeatedly regrets the killing.

Terrible acts have been committed by those who have felt compelled to kill because of a mental health condition and many of the victims’ families have a hard time understanding what could drive someone to do those terrible things. I only need to say the names “Vince Weiguang Li” or “Rohinie Bisesar” to evoke a visceral reaction in certain people. The Voices, however, doesn’t ask us to forgive anyone’s crimes; it offers a window into the interior life of someone who commits murder at the behest of the voices in his head. It also shows how even those who aren't subject to delusions have inner voices which can cause immense psychological harm.

The world in which unmedicated Jerry lives is bright and cheery; the world in which medicated Jerry lives is like something out of Hoarders. Without his ongoing interactions with Bosco and Mr. Whiskers, Jerry feels frighteningly and overwhelmingly alone. That’s what taking medication does to him.

No doubt we’ve heard the stories of schizophrenics who don’t take their meds because it makes them feel weird, depressed, different, or miserable. Satrapi and Perry make this visually apparent through the reality of Jerry’s decrepit, disgusting apartment while Reynolds successfully conveys to us what it feels like to be trapped in that dismal world.

His hallucinatory flashbacks to the unfortunate demise of his mother at his own hands are heartbreaking, especially when Jerry’s hateful, abusive stepfather is depicted as exacerbating the situation. How could we not feel sorry for what Jerry went through, none of which was his own fault?

Once the depths of Jerry’s disease and despair have been revealed, the comedy in The Voices feels more like the only way he can escape his tortured existence. It’s the fear of being alone that drives him to resist taking his meds, to continue seeking that fantasy world with Bosco, Mr. Whiskers, and the love and affection of a genuinely nice co-worker named Lisa. It’s a fear that we can all relate to, whether or not we suffer from the delusions of paranoid schizophrenia and it’s what makes The Voices so smart and ultimately, so special.

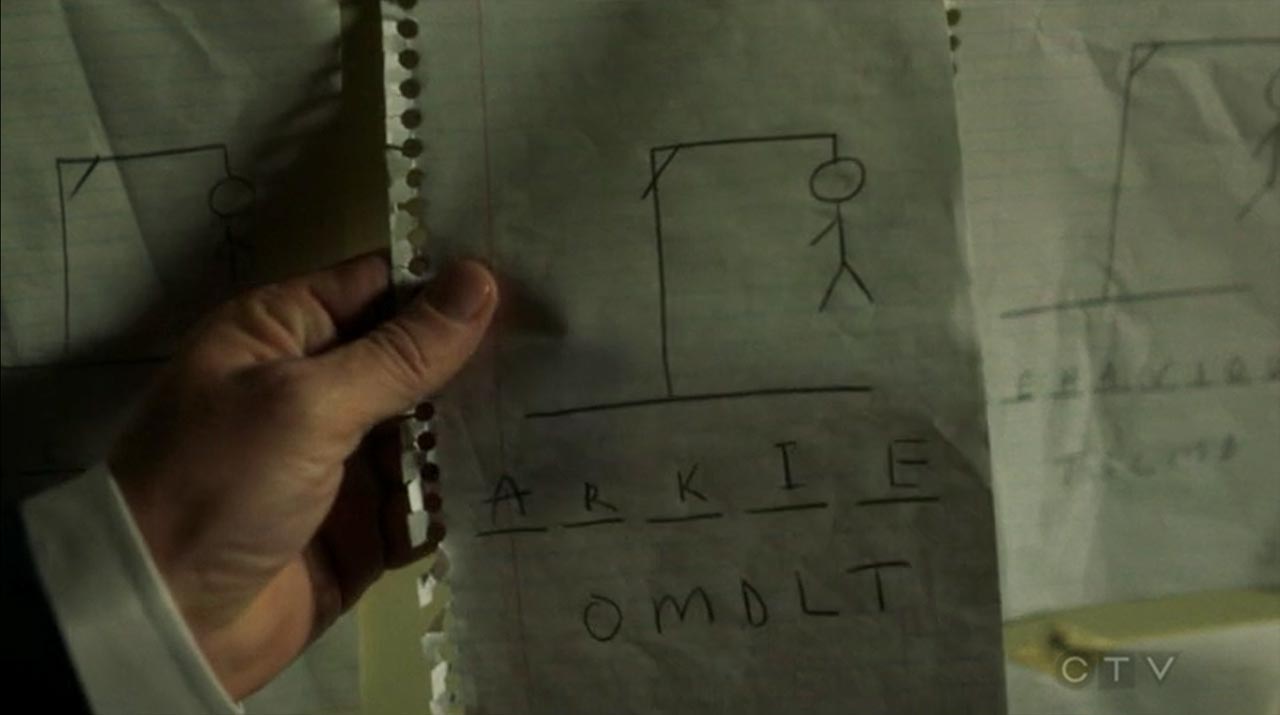

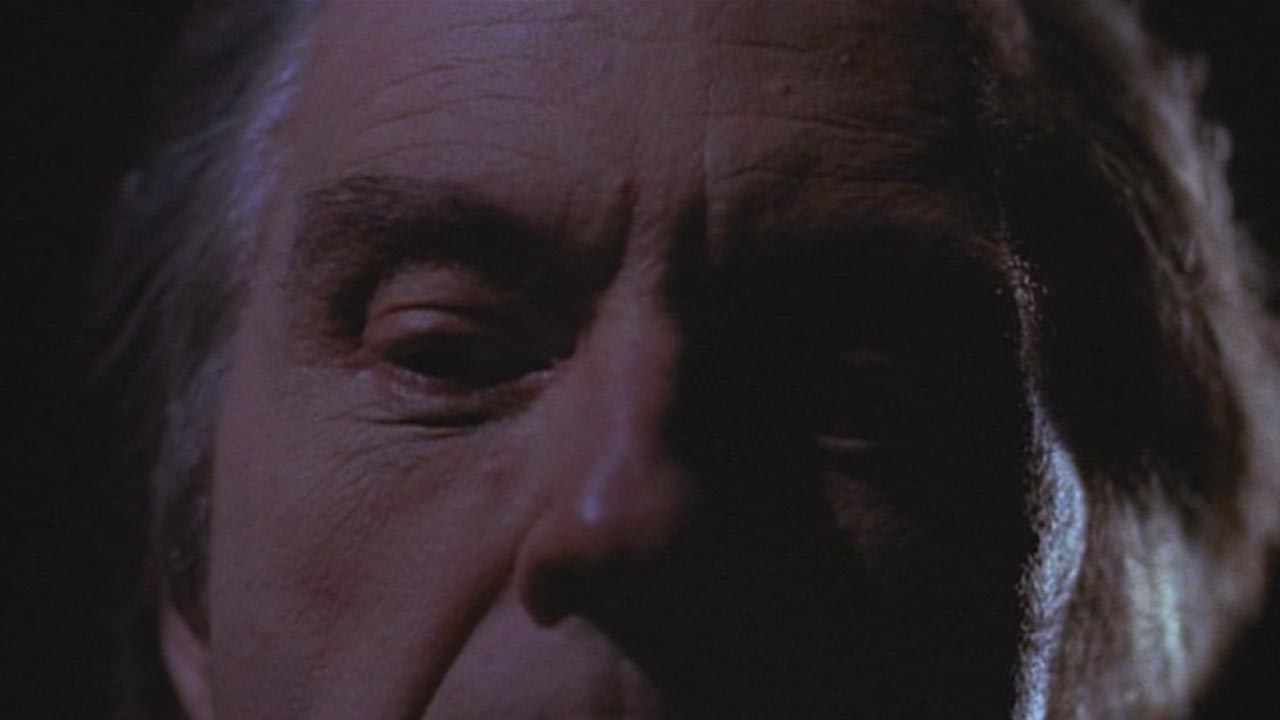

There have been many horror films about nightmares, including one popular franchise starring a guy with a red and green striped sweater, but they all have one thing in common: they clearly announce their intent in their titles. The scariest thing about an actual nightmare is not being able to tell the difference between the dream world and waking life. In that respect, Phantasm stands tall amongst its nightmare movie brethren, and not just because it stars six-foot-four actor Angus Scrimm.

If I had seen Phantasm in 1979, no doubt it would have traumatized me. As a kid who suffered from insomnia, nightmares, and panic attacks, the iconic visuals in the film feed into the typical but frequently debilitating fears of the easily spooked: death, cemeteries, funerals, things under the bad, masked creatures, and of course, the imposing and mysterious Tall Man. Since the main protagonist of the film is a 13-year-old kid, it only makes the creeping terror of Phantasm’s narrative more frightening.

Many classic tales are based on the simple idea that no one believes the protagonist; no one will entertain the possibility that the things he or she insists are happening have actually happened or are even real. While this trope is often utilized with women in horror films—with Let’s Scare Jessica To Death and Don’t Be Afraid Of The Dark being my two favorite examples—there are many examples of fiction when this lack of belief from others plagues a child, such as The Wizard of Oz.

In Phantasm, Mike’s parents were killed two years ago, and his older brother Jody wants to protect him. When Jody attends the funeral of his friend Tommy, he warns Mike to stay home lest it freak him out too much. Mike doesn’t listen and this sets some of the events of the film in motion. As things get more and more dangerous, Jody continually tells Mike to stay home, stay safe, stay away from the danger, but Mike always finds a way.

In the beginning of Phantasm, Mike visits a psychic and expresses concern that Jody is leaving. The film then cuts to a shot of Jody’s car driving down the street. It pulls into a driveway and Mike and Jody get out and while Mike works on the engine, Jody tells his friend Toby that he’s unsettled by the way Mike is always following him around. The movie cuts away from this conversation to show an example of this, and by not changing the visual style of the film or cutting back to Jody having the conversation, it’s difficult at first to know whether this image is a flashback or happening in the present, especially when this is followed up by a continuation of Mike talking to the psychic. Director Don Coscarelli does this frequently throughout Phantasm, using dialogue as a kind of sound bridge between scenes to indicate the fluid nature of reality.

It’s true that Mike always seems to be present no matter where Jody goes: when Jody is riding his bike, when Jody is at a local watering hole hitting on a woman, when Jody is having sex with the woman a few minutes later. This is much like the way that we are omniscient in dreams, bearing witness to the activities of others in situations when were not physically present.

There are a few instances where Mike does something and then Jody does the exact same thing, or vice versa. Mike breaks into the funeral home to find more about the Tall Man, when he is attacked by the dwarves. Later, Jody does the same thing, using the same window to enter the building, and is also attacked. When Reggie takes Mike to Sally’s house for safekeeping, Jody dreams of being pulled through the wall by two dwarves, a scene repeated at the end of the movie, only with Mike instead.

Later, when Mike is lying on the ground after being attacked by the dwarves in Sally’s car, the film cuts back and forth between him on the ground and Jody’s face, almost as if Jody can see what is happening to Mike. Is the Jody of the film just Mike’s dream world version of his brother?

These are not the only two characters blurred together in Phantasm. The Lady in Lavender stabs and kills Tommy at the beginning of the film. A close up on her face cuts to a close up of the Tall Man’s face but this is never explained. This visual is repeated when she stabs Reggie at the end of the film. This is similar to the way characters in a dream often “become” someone else without explanation, or the way that a dream character looks like one person but you somehow “know” they are another person.

Mike is able to prove to Jody that the Tall Man is a real threat when he cuts off his fingers and brings one home. But when he and Jody decide to bring the severed finger to the police, in typical dream fashion, it is inexplicably transformed into a large insect that proceeds to attack them both. Reggie is soon brought into their shared nightmare when he arrives at the house and sees what’s going on.

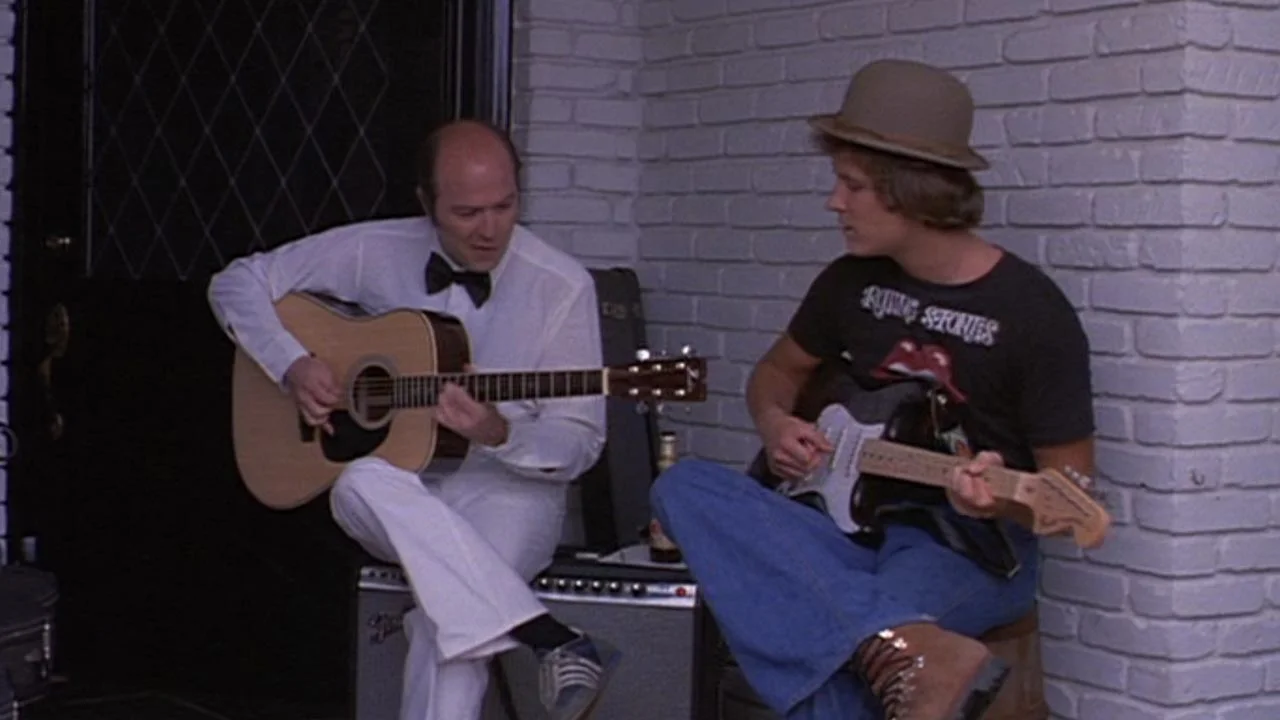

Reggie is not only one of Jody’s best friends, he is also a guitarist and singer, as is shown when Jody is playing guitar and singing and Reggie stops by. Reggie immediately picks up his guitar and starts playing and singing, too, even though this is an unfinished song that Jody has been working on. Reggie’s speaking voice even sounds like Jody’s. At the end of the film, Reggie says that he’ll never be able to replace Jody in Mike’s life but that he’s going to try. Is Reggie real, or just another version of Jody?

Are the events we see in Phantasm a collection of Mike’s dreams? There are many shots of Mike lying in bed sleeping, which suggest that the entirety of the film is a dream. After all, only in a dream would it be possible for the Tall Man to lift a heavy coffin by himself. Only in a dream would a strange silver sphere hurtle through the air and kill people by piercing their skulls. Only in a dream would corpses be crushed into dwarves to be used as slaves on another plant. Only in a dream would someone bleed yellow liquid when killed instead of red blood. Only in a dream would a photograph move and the person in it look directly into your eyes.

Interestingly, Jody sees the Tall Man before Mike does, but he only registers as peculiar, not evil. It’s Mike who tries to convince Jody that the Tall Man is something supernatural. When Mike sees the Tall Man walking down the street, he’s paralyzed by terror. The Tall Man stands right behind Reggie’s ice cream truck, breathing in the cold fumes, but Reggie—moving in slow motion—doesn’t seem aware that anyone is nearby. Is the Tall Man real or just a figment of Mike’s dream world imagination? The granddaughter of the psychic he visits tells Mike that “fear is the killer” that “it’s all in your mind,” but then she disappears into the mysterious door at the funeral home.

So what is real and what is not real in Phantasm? It’s impossible to decide, which makes it one of the most disturbingly accurate portrayals of nightmare logic in cinema.

First it was Whitley Streiber’s Communion. The author of horror novels like The Wolfen and The Hunger was roundly ridiculed for his first person, non-fiction novel about alien abduction in 1987, but this didn’t stop him from writing a follow up, Transformation, a year later. The book editor at The L.A. Times' book editor even removed Transformation from the non-fiction best-seller list despite the fact that it was published as a non-fiction account. WIKI LINK

Then, it was The X-Files, which once again brought little green men – or grey men, to be more accurate – into pop culture consciousness. The alien abduction mythology of the show remains divisive, but it did spark enough of a debate to make shows like Sightings and Encounters: The Hidden Truth fairly popular in the 1990s.

By 2015, however, the number of reality shows on the topic, such as the outrageous Ancient Aliens, and the increasing discussion of sleep paralysis as a possible explanation for alien abduction stories, means that a lot of people don’t find aliens a plausible or scary subject for a horror movie.

Ejecta, written by Tony Burgess (Pontypool) and directed by Chad Archibald (The Drownsman, Bite) and Matt Wiele, opens with a frightfully intriguing premise: the aliens aren’t little green men or Greys and their abduction doesn’t involve blinding white lights and tractor beams, but something more insidious.

Bill Cassidy has been off the grid for years, with the exception of his untraceable online postings as Spider Nevi, a man who claims to have been tormented by his encounter with an alien presence. Fanboy Joe Sullivan tracks him down and begs Cassidy for a videotaped interview because he believes his story.

Like Pontypool, Ejecta plants a tantalizing suggestion: what if the evil forces that seek us out can’t be seen with the eyes, but instead are felt in the mind? Other films have tried to expand upon this idea with mixed results. 1982’s Xtro opens with an amazing shot of an alien and a storyline about a personality takeover but devolves into a bunch of gory birth scenes and toys that come to life (2012’s Almost Human takes on this same idea and dispenses with any alien visuals to create a much better version of the story). The Hidden, the 1987 feature with Kyle McLachlan and Michael Nouri, does a marvelous job at making the unseen entity seem uncanny and terrifying, even though it has a physical form which resides inside the host’s body (kind of like the cockroach alien from Men In Black but much smaller and less obvious).

How does Ejecta compare? As Cassidy, Julian Richings is as superbly creepy as usual. He’s gaunt and haunted and the idea of having something inside of your brain that you can’t get rid of is truly terrifying. But Ejecta fails when it relies too heavily on the tired trope of shaky cam found footage as a method of exposition and eventually shows us the alien itself. The film attempts to deviate from the trope by explaining that the alien body is just a host for the alien intelligence, but once we see the creature laid out on a table, the fake “alien autopsy” video is the first thing that comes to mind, and like Cassidy’s alien, we can’t get it out of our heads.

It’s a shame because Ejecta has a lot of promise from a narrative perspective but it feels like yet another movie that could have benefited from fewer special effects.

In 1936, 18-year-old writer Robert H. Barlow penned the short story The Night Ocean with the help of his friend and mentor, H.P. Lovecraft. As much as it explores the kind of unfathomable frights that Lovecraft is known for, the tale also has a distinctly lighter, but no less unsettling touch.

Like much of Lovecraft's work, The Night Ocean deals with those liminal spaces that are more disconcerting than specific details. The unnamed narrator of the story is taking a vacation in an isolated, one-room cabin on the beach near a town named Ellston after a year spent toiling over a mural submitted to a competition. At first he basks quite literally in the immense sunlight of the place, but soon a pall comes over his existence and he can't shake it off.

"I did not wish to see anything but the expanse of pounding surf and the beach lying before my temporary home," he muses, making it obvious that he will, of course, see something else. Yet such a device is not predictable or cliché, but instead sets up the state of vague apprehension that permeates the story, what the narrator describes as "an uneasiness which had no very definite cause."

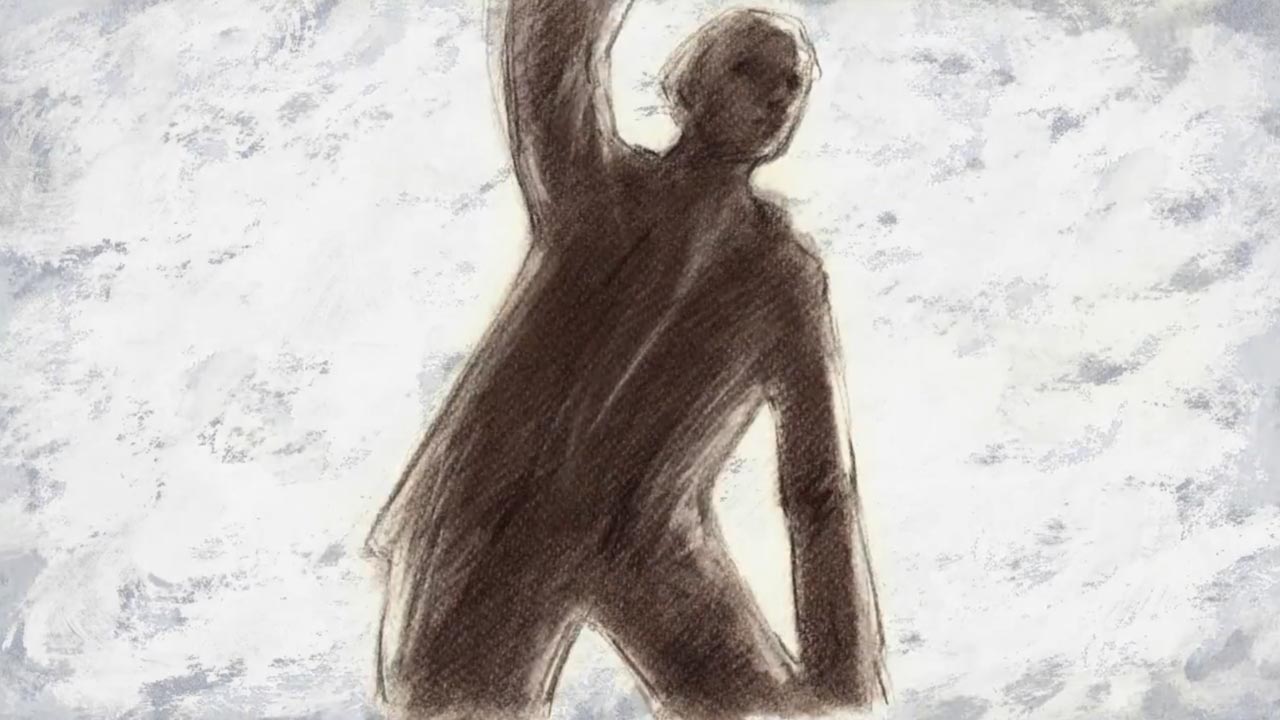

The short film "The Night Ocean," directed and animated by María Carmen Lorenzo Hernández, adapts the story into 12 gauzy and sometimes ghastly minutes. Hernández utilizes an entirely appropriate animation style for a story about an artist. Much of the film (save for one brief snippet of what seems to be an old home movie on faded film stock) alternates between watercolor and pencil drawings.

Furthermore, she transforms the first person narrative style into a visual diary by having the actual frames look like sketches in a notebook, right down to the center binding and edges of pages. It's an ingenious way to create an aura of ideas, perceptions, and feelings and also remains true to the mood of the original text at the same time.

"The Night Ocean" also includes a voice-over track during most of the running time, which again, is consistent with the story. Rather than just having someone read the text over the visuals, the events are shuffled around and shortened. The film dispenses with the VO in a couple of key sequences, which are also the most disturbing segments of the film itself. However, the most upsetting scene in the original story is jettisoned, possibly because it would have dipped too far into horror territory and contrasted strongly with the overall tone of the film.

That said, it's still a haunting piece of work. The rough pencil drawings on coarsely textured paper look like chalk on a blackboard at times and that wavering, wobbly look fits with the ephemeral nature of the story itself as well as the frights it contains.

"To shape these things on the wheel of art," ponders the narrator, "to seek to bring some faded trophy from that intangible realm of shadow and gossamer, requires equal skill and memory." With "The Night Ocean," María Carmen Lorenzo Hernández has, intriguingly enough, done just that.

There has been a lot of positive buzz surrounding Room 237 director Rodney Ascher's latest documentary, The Nightmare. In the film, Ascher interviews eight different people (seven in North America, one in the UK) about their experiences with sleep paralysis.

When I first heard about this film and how scary it was supposed to be, I thought, "Yeah, I've had sleep paralysis. It's weird but not scary." It wasn't until I saw the trailer that I realized why everyone was so terrified by this movie.

"For many, sleep is fraught with things worse than bad dreams."

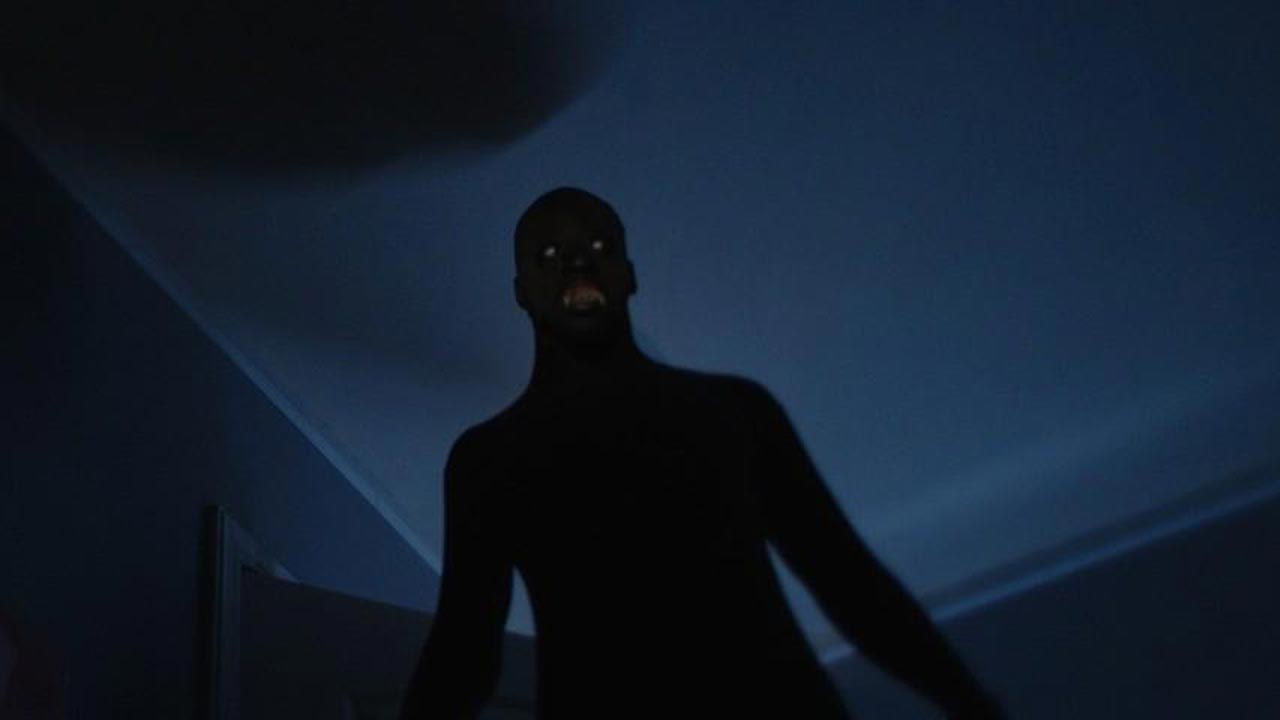

When I finally got up the courage to watch The Nightmare, it was during the daytime (I'm not stupid). Ascher adds reenactments to the individual descriptions of sleep paralysis, including visual interpretations of "the shadow people" and "the hat man," dark figures that appear to those suffering from sleep paralysis. In many cases, these figures speak to and even threaten their "victims." I had no idea anyone experienced this during sleep paralysis.

In addition to the absolutely unnerving stories and reenactments, I became fascinated by the idea that perhaps sleep paralysis is responsible for much of our horror iconography. The red lighting and the image of Hat Man made me think of classic Giallo films like Blood And Black Lace and I wondered if perhaps those films were also inspired by the history of this phenomenon. Ana M. mentions an incident where she felt like she was being sexually assaulted by one of these nocturnal visitors, which immediately reminded me of The Entity.

Although no one mentions Giallo films or The Entity in The Nightmare, Ascher does confirm that A Nightmare On Elm Street was inspired by director Wes Craven's fascination with sleep paralysis. In addition, Communion (based on Whitley Streiber's book of the same name), Jacob's Ladder, and Insidious are also referenced by those who have suffered from sleep paralysis as good interpretations of their experiences..

These movies are fiction, though. (I hope.) I already knew that the idea of an incubus or succubus had been partially explained by hypnagogic states of consciousness, but could astral projection, vampires, or even alien visitations be explained by this phenomenon?

The Nightmare discusses how universal these occurences are; nearly every culture has tales of shadow people or red-eyed demons that visit people in their sleep. Yet, despite the global preponderance of these stories, each person's encounters seem uniquely tailored to them. In at least two instances in the film, for example, the figures address the person by name or say things like "I will find you" or "I know who you are." This tension between the universal and the personal is intriguing.

Carl Gustav Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist who founded the school of thought known as analytical psychology, addressed such a tension in his theories on archetypes. According to Wikipedia, archetypes "are inherited potentials which are actualized when they enter consciousness as images or manifest in behavior on interaction with the outside world." Jung believed that "evolutionary pressures have individual predestinations manifested in archetypes."

Having suffered from insomnia and panic attacks my whole life, I was also struck by the similarities between some of the incidents described in the film and my own life. I've never seen shadow people during any of my own episodes of sleep paralysis (thank the gods), but the stress that the such visitations caused most of the people interviewed reminded me of being an over imaginative kid who worried all the time about everything, believing that if I thought about something enough I could conjure it into existence somehow. One subject, Chris C., thought he could keep the visitations at bay "if certain requirements were met," a textbook definition of OCD if I've ever heard one. His idea was to leave televisions on while he fell asleep, a technique that I used for most of my life. But it eventually stopped working for him.

"Those moments, they stare back at you. You don't remember them; they remember you. You turn around, there they are." - True Detective Season 2, Episode 4 "Down Will Come"

Although some of the subjects in The Nightmare have dealt with these problems, whether converting to Christianity or deciding to accept that sleep paralysis might kill them (a sobering thought), doctors have not helped any of them. Despite how frequently such sleep paralysis visitations occur, both on a global and individual level, and how negatively it has impacted lives, physicians and therapists seem content to respond to their pleas for help with "it's just sleep paralysis" and don't provide them any relief.

So is it really sleep paralysis or is it something else? Although Kate A. explains her experiences rationally, she does state, "you can't put logic onto liminal situations." The fact that making the "positive lifestyle changes" their doctors suggested did absolutely nothing to stop the traumatic visitations for these people is disconcerting. In some cases, it's contagious, as some who suffer from it have actually passed it on to others. Are these apparitions nothing more than a sleep disorder, mental illness, or as Stephen P. speculates, could they be the result of the theory that we reside in multiple dimensions?

The most troubled person in The Nightmare is easily Chris C., who seems to have had the most negative and persistent experiences with sleep paralysis, which probably results in his attempts at humorous storytelling and his clearly fatalistic attitude. "It will kind of learn how to adapt to you. If you try to avoid it, it will find you and it will make it happen somehow," he says. Considering the lack of resolution for most of these people, his statement might be the scariest thing in all of The Nightmare.

In preparation for the upcoming six-episode season of The X-Files in 2016, a rewatch of all nine seasons of the original series seemed like a timely idea, especially since I never finished the last two.

In the midst of all the "remember the '90s" nostalgia about clothing, cars, and how ridiculously youthful both David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson look, I realized something important: I finally get it.

It's not that I finally "get" why the show was such a big deal. I was a huge fan of The X-Files when it first aired in the early '90s. It was my pre-Hannibal Hannibal, with the same creepy aspects that I loved about The Twilight Zone and Twin Peaks, plus a dash of Unsolved Mysteries. In several cases, it actively frightened me ("The Host," "Hungry," and "Folie À Deux" immediately come to mind).

What finally makes sense to me is Fox Mulder's unwavering dedication to finding the truth that he insists is out there. Fear of the unknown is one of the most primal fears, but what about the fear of not knowing? That's the precise fear that drives Fox Mulder.

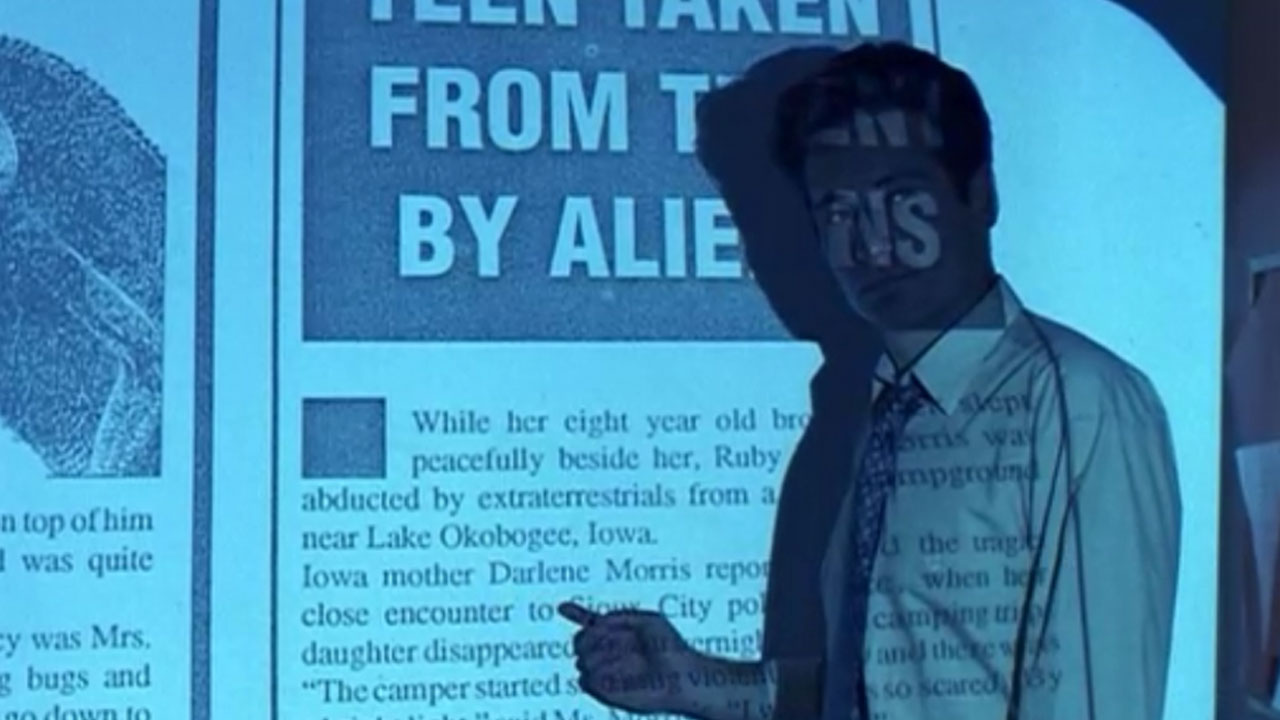

Episode S104, "Conduit," finds Mulder and Scully in Iowa, where Ruby Morris has disappeared in the middle of the night, during what her mother Darlene describes as a blinding flash of light. What makes the incident intriguing to Mulder is that this light fits in with several alien abduction stories he's uncovered in the X-Files themselves.

Scully, along with the audience, thinks that Mulder is drawn to this case because of its similarities to the events surrounding his own missing sister, Samantha, which he had revealed to her in the show's pilot episode. He denies this, insisting that Darlene's own past is the hook. When she was in Girl Scouts, Darlene, along with a few others, saw a UFO in the same Lake Ogobogee area where Ruby went missing. Mulder is convinced that those same aliens have come back for Darlene's daughter.

More is revealed during the course of this episode suggesting that perhaps Ruby was just a runaway teen in trouble. Darlene's younger child, Kevin, meanwhile, has become engrossed in writing down thousands of pages of binary code and like Carol Anne in Poltergeist, tells Mulder that the messages are coming from the TV.

Mulder is intent on finding out more from Kevin, but the NSA eventually shows up and starts ransacking the Morris home, taking Kevin in for questioning because some of the stuff he's been writing might be a threat to national security. After that, Darlene warns Mulder and Scully to back off. Scully tells Mulder that solving this case won't bring his sister back. He swears he's not giving up on Ruby until they find a body.

Not long afterward, Ruby reappears in the woods, confused, but seemingly unharmed. Mulder pleads with Darlene to be receptive to her daughter's memories of what actually happened. "She should be encouraged to tell her story," he says gently, "not to keep it inside, it's important that you let her." Darlene dismisses him, saying that Ruby can't remember anything. But Mulder persists, and we see for the first time what Scully has tried to get him to admit, and what the people who assigned Scully to the X-Files believe is Mulder's greatest weakness as well as his greatest strength: his desire to know.

"But she will remember one day, one way or another, even if it's only in dreams. And when she does, she's going to want to talk about it, she's going to need to talk about it."

It's then that I finally understood why Mulder spent so many years searching. Losing a family member to death is one thing. I lost two grandparents and a stepfather within the same year when I wasn't yet a teenager. That was awful. Having a sister vanish in front of you with no idea where she went, who took her, or what happened to her must be unbearable.

For those in search of missing family members, the fear conjured by simply not knowing must be agony. For Mulder, it has the added indignity of marking him forever as a fanatic and making authorities less likely to dig into what he suspects are the real reasons behind her disappearance.

"Conduit" ends with Scully listening to a tape of one of Mulder's therapy sessions, in which he's been hypnotized and asked to recall the events of that night. It's utterly heartbreaking and for the first time when watching this episode, I truly felt his fear. It's not a fear of the unknown or even a fear of the uncanny, but the fear of not knowing.

I thought: what if it was my own sister who'd disappeared in the middle of the night? What if no one believed me when I told them what I thought happened? What if I never truly found out? What if I never saw her again? Just thinking about that scares the hell out of me. Not long after that series of deaths when I was a child, my dog disappeared into the night, never to be seen again, either alive or dead. It was so traumatizing I didn't even write about it in my diary. In fact, I can barely remember it.

Even though Mulder remembers what happened that night, it's with a couple of caveats. His memories haven't helped him or his sister; the rest of his family has been torn apart.. He's become privy to the memories themselves, but separated from the act of remembering, something which would instill terror into anyone's heart.

Mulder's curiosity is both a blessing and a curse for him, but it's the fear at the core of that curiosity that makes "Conduit" a remarkable episode and proves that The X-Files still compelling after all these years.