“A Monstrous Sacrifice:” ‘IT’ as American Folk Horror

Not only is the 2017 cinematic adaptation of Stephen King's 'IT' scary, it also deserves a place in the American Folk Horror canon.

Read More

Not only is the 2017 cinematic adaptation of Stephen King's 'IT' scary, it also deserves a place in the American Folk Horror canon.

Read More

The announcement that the Vanguard Programme will no longer be a part of the Toronto International Film Festival leaves a giant hole in my heart.

Read More

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s latest film, 'Creepy,' goes above and beyond what its title implies.

Read More

Some of the best horror movies traffic in the premise that someone who appears to be the initial villain of the film isn’t actually the big boss.

Read More

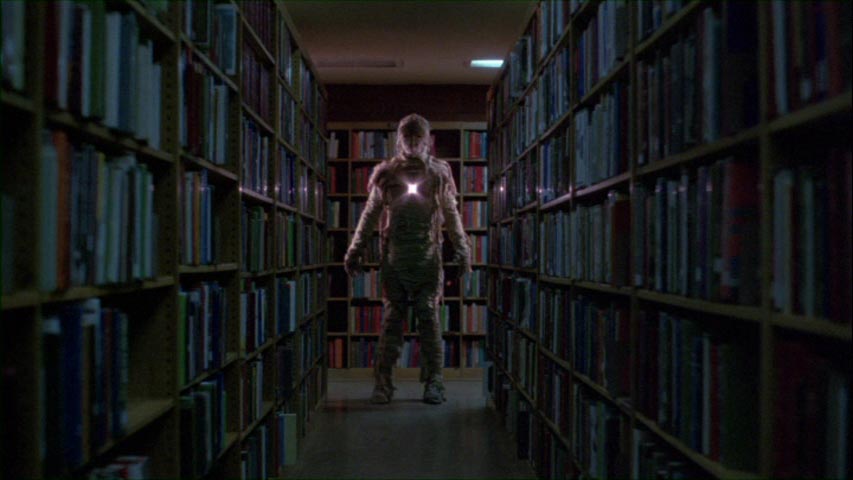

If ever there was a film that exemplifies what Everything Is Scary is about, it would be The Void.

Read More

Perhaps the best way to explain why some movies are scary is to look closely at one that isn't scary at all.

Read More

Dispensing horror movie tropes for something more subtle and spooky, They Look Like People pushes the boundaries of the genre.

Read More

The Neon Demon, on the surface, seems to be about a lot of things, but it portrays a world of very real horror.

Read More

The titular beast in the film Sleeping Giant reveals itself in subtle and frightening ways.

Read More

Intruders: what happens when a mental health issue is used as a device to entice viewers into watching a movie about a totally different kind of pathology.

Read MoreThe woman said, “The serpent deceived me, and I ate.”

Read More

Baskin is a stunning shock to the system for horror fans. Miss it at your peril.

Read More

What makes a man into a monster?

Read MoreJerry seems like a nice guy. He works at a bathtub factory in Milton and lives in the upstairs apartment of an old bowling alley with his two pets, Bosco (the boxer) and Mr. Whiskers (the yellow tabby cat). Jerry is kind of shy and awkward, but his therapist encourages him to participate in planning the annual office picnic. Jerry is also smitten with Fiona, the beautiful English woman who works with him, and hopes that he’ll be able to woo her with his humble charms.

The Voices begins like a sweet romantic comedy with a slightly dark undertone. As Jerry, Ryan Reynolds is less Green Lantern and more Clark Kent. We find out right away that he talks to Bosco and Mr. Whiskers and that they talk back. We figure he’s got some kind of schizophrenia, which is confirmed when he fudges the details about hearing voices and taking his meds. It doesn’t seem like that big of a deal until Fiona is revealed to be something of a self-centered creep and Jerry accidentally-on-purpose stabs her to death.

It’s a shocking scene in a movie that, up until that point, feels like a quirky art-house film. Director Marjane Satrapi and writer Michael R. Perry shift the tone of The Voices in an uncomfortable direction, one that almost feels like it was borrowed from another genre. It’s a stylistic gamble that actually pays off due to Ryan Reynolds’ sympathetic portrayal of Jerry and some straightforward talk about mental illness.

In her review of The Voices, The Spectator’s Deborah Ross doesn’t mince words about how much she “bitterly” resents having to watch the movie at all, describing it as “hateful” and “repellent” and singling out its tone shift for particular condemnation. I have to wonder if we saw the same movie. There are certainly horror films that seem to glorify the killer’s grisly acts or which revel in misogyny for misogyny’s sake (the recent remake of Maniac, for example), but The Voices doesn’t even show most of the crimes that Jerry commits. The majority of his murders take place off screen and he clearly, obviously, and repeatedly regrets the killing.

Terrible acts have been committed by those who have felt compelled to kill because of a mental health condition and many of the victims’ families have a hard time understanding what could drive someone to do those terrible things. I only need to say the names “Vince Weiguang Li” or “Rohinie Bisesar” to evoke a visceral reaction in certain people. The Voices, however, doesn’t ask us to forgive anyone’s crimes; it offers a window into the interior life of someone who commits murder at the behest of the voices in his head. It also shows how even those who aren't subject to delusions have inner voices which can cause immense psychological harm.

The world in which unmedicated Jerry lives is bright and cheery; the world in which medicated Jerry lives is like something out of Hoarders. Without his ongoing interactions with Bosco and Mr. Whiskers, Jerry feels frighteningly and overwhelmingly alone. That’s what taking medication does to him.

No doubt we’ve heard the stories of schizophrenics who don’t take their meds because it makes them feel weird, depressed, different, or miserable. Satrapi and Perry make this visually apparent through the reality of Jerry’s decrepit, disgusting apartment while Reynolds successfully conveys to us what it feels like to be trapped in that dismal world.

His hallucinatory flashbacks to the unfortunate demise of his mother at his own hands are heartbreaking, especially when Jerry’s hateful, abusive stepfather is depicted as exacerbating the situation. How could we not feel sorry for what Jerry went through, none of which was his own fault?

Once the depths of Jerry’s disease and despair have been revealed, the comedy in The Voices feels more like the only way he can escape his tortured existence. It’s the fear of being alone that drives him to resist taking his meds, to continue seeking that fantasy world with Bosco, Mr. Whiskers, and the love and affection of a genuinely nice co-worker named Lisa. It’s a fear that we can all relate to, whether or not we suffer from the delusions of paranoid schizophrenia and it’s what makes The Voices so smart and ultimately, so special.

First it was Whitley Streiber’s Communion. The author of horror novels like The Wolfen and The Hunger was roundly ridiculed for his first person, non-fiction novel about alien abduction in 1987, but this didn’t stop him from writing a follow up, Transformation, a year later. The book editor at The L.A. Times' book editor even removed Transformation from the non-fiction best-seller list despite the fact that it was published as a non-fiction account. WIKI LINK

Then, it was The X-Files, which once again brought little green men – or grey men, to be more accurate – into pop culture consciousness. The alien abduction mythology of the show remains divisive, but it did spark enough of a debate to make shows like Sightings and Encounters: The Hidden Truth fairly popular in the 1990s.

By 2015, however, the number of reality shows on the topic, such as the outrageous Ancient Aliens, and the increasing discussion of sleep paralysis as a possible explanation for alien abduction stories, means that a lot of people don’t find aliens a plausible or scary subject for a horror movie.

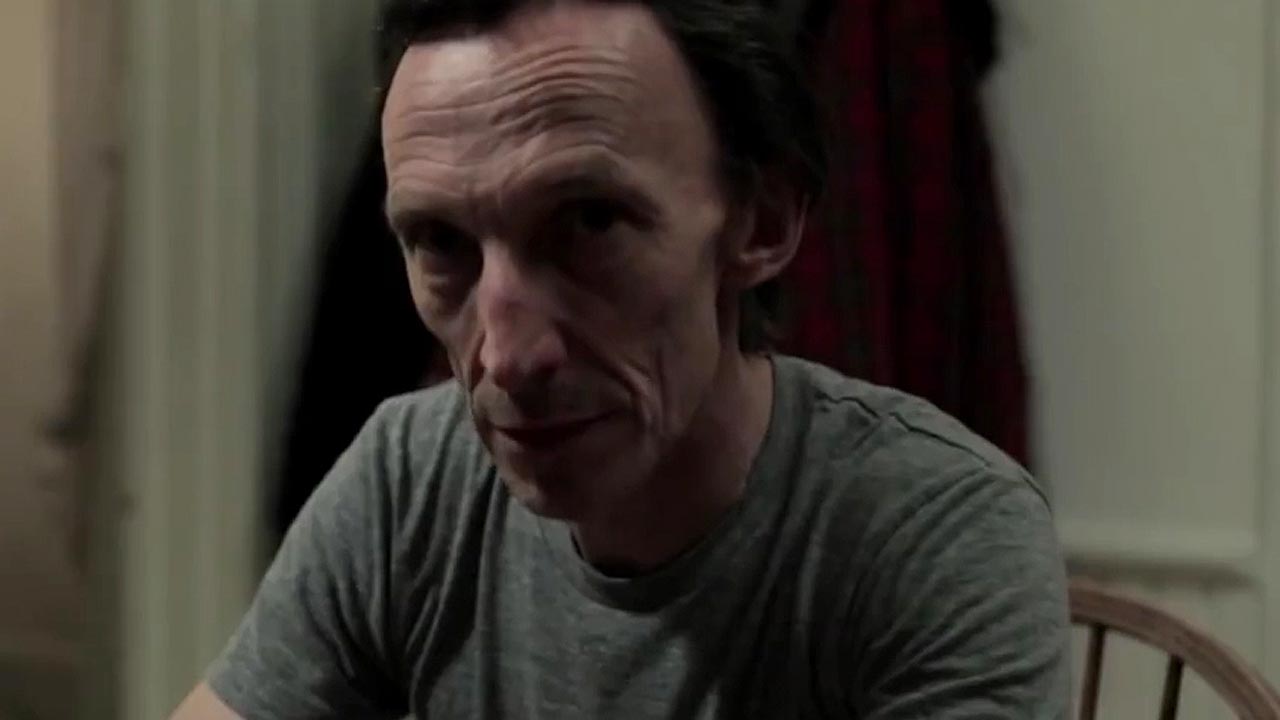

Ejecta, written by Tony Burgess (Pontypool) and directed by Chad Archibald (The Drownsman, Bite) and Matt Wiele, opens with a frightfully intriguing premise: the aliens aren’t little green men or Greys and their abduction doesn’t involve blinding white lights and tractor beams, but something more insidious.

Bill Cassidy has been off the grid for years, with the exception of his untraceable online postings as Spider Nevi, a man who claims to have been tormented by his encounter with an alien presence. Fanboy Joe Sullivan tracks him down and begs Cassidy for a videotaped interview because he believes his story.

Like Pontypool, Ejecta plants a tantalizing suggestion: what if the evil forces that seek us out can’t be seen with the eyes, but instead are felt in the mind? Other films have tried to expand upon this idea with mixed results. 1982’s Xtro opens with an amazing shot of an alien and a storyline about a personality takeover but devolves into a bunch of gory birth scenes and toys that come to life (2012’s Almost Human takes on this same idea and dispenses with any alien visuals to create a much better version of the story). The Hidden, the 1987 feature with Kyle McLachlan and Michael Nouri, does a marvelous job at making the unseen entity seem uncanny and terrifying, even though it has a physical form which resides inside the host’s body (kind of like the cockroach alien from Men In Black but much smaller and less obvious).

How does Ejecta compare? As Cassidy, Julian Richings is as superbly creepy as usual. He’s gaunt and haunted and the idea of having something inside of your brain that you can’t get rid of is truly terrifying. But Ejecta fails when it relies too heavily on the tired trope of shaky cam found footage as a method of exposition and eventually shows us the alien itself. The film attempts to deviate from the trope by explaining that the alien body is just a host for the alien intelligence, but once we see the creature laid out on a table, the fake “alien autopsy” video is the first thing that comes to mind, and like Cassidy’s alien, we can’t get it out of our heads.

It’s a shame because Ejecta has a lot of promise from a narrative perspective but it feels like yet another movie that could have benefited from fewer special effects.

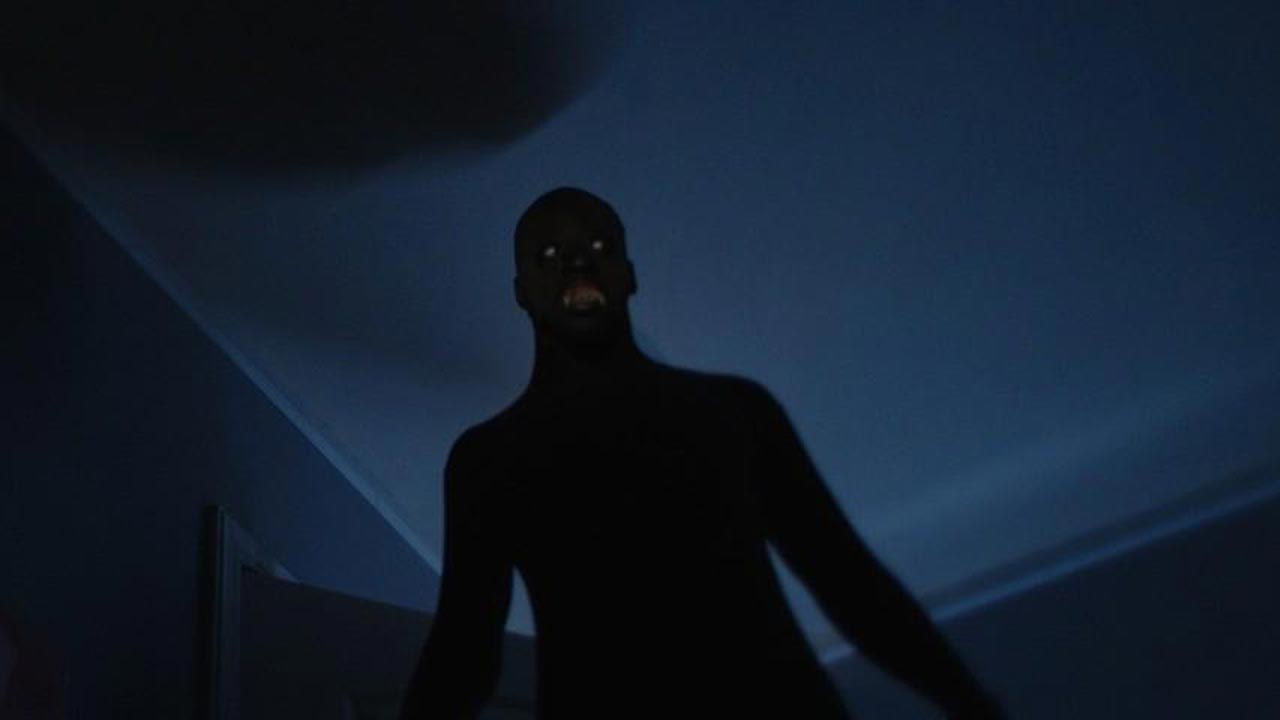

There has been a lot of positive buzz surrounding Room 237 director Rodney Ascher's latest documentary, The Nightmare. In the film, Ascher interviews eight different people (seven in North America, one in the UK) about their experiences with sleep paralysis.

When I first heard about this film and how scary it was supposed to be, I thought, "Yeah, I've had sleep paralysis. It's weird but not scary." It wasn't until I saw the trailer that I realized why everyone was so terrified by this movie.

"For many, sleep is fraught with things worse than bad dreams."

When I finally got up the courage to watch The Nightmare, it was during the daytime (I'm not stupid). Ascher adds reenactments to the individual descriptions of sleep paralysis, including visual interpretations of "the shadow people" and "the hat man," dark figures that appear to those suffering from sleep paralysis. In many cases, these figures speak to and even threaten their "victims." I had no idea anyone experienced this during sleep paralysis.

In addition to the absolutely unnerving stories and reenactments, I became fascinated by the idea that perhaps sleep paralysis is responsible for much of our horror iconography. The red lighting and the image of Hat Man made me think of classic Giallo films like Blood And Black Lace and I wondered if perhaps those films were also inspired by the history of this phenomenon. Ana M. mentions an incident where she felt like she was being sexually assaulted by one of these nocturnal visitors, which immediately reminded me of The Entity.

Although no one mentions Giallo films or The Entity in The Nightmare, Ascher does confirm that A Nightmare On Elm Street was inspired by director Wes Craven's fascination with sleep paralysis. In addition, Communion (based on Whitley Streiber's book of the same name), Jacob's Ladder, and Insidious are also referenced by those who have suffered from sleep paralysis as good interpretations of their experiences..

These movies are fiction, though. (I hope.) I already knew that the idea of an incubus or succubus had been partially explained by hypnagogic states of consciousness, but could astral projection, vampires, or even alien visitations be explained by this phenomenon?

The Nightmare discusses how universal these occurences are; nearly every culture has tales of shadow people or red-eyed demons that visit people in their sleep. Yet, despite the global preponderance of these stories, each person's encounters seem uniquely tailored to them. In at least two instances in the film, for example, the figures address the person by name or say things like "I will find you" or "I know who you are." This tension between the universal and the personal is intriguing.

Carl Gustav Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist who founded the school of thought known as analytical psychology, addressed such a tension in his theories on archetypes. According to Wikipedia, archetypes "are inherited potentials which are actualized when they enter consciousness as images or manifest in behavior on interaction with the outside world." Jung believed that "evolutionary pressures have individual predestinations manifested in archetypes."

Having suffered from insomnia and panic attacks my whole life, I was also struck by the similarities between some of the incidents described in the film and my own life. I've never seen shadow people during any of my own episodes of sleep paralysis (thank the gods), but the stress that the such visitations caused most of the people interviewed reminded me of being an over imaginative kid who worried all the time about everything, believing that if I thought about something enough I could conjure it into existence somehow. One subject, Chris C., thought he could keep the visitations at bay "if certain requirements were met," a textbook definition of OCD if I've ever heard one. His idea was to leave televisions on while he fell asleep, a technique that I used for most of my life. But it eventually stopped working for him.

"Those moments, they stare back at you. You don't remember them; they remember you. You turn around, there they are." - True Detective Season 2, Episode 4 "Down Will Come"

Although some of the subjects in The Nightmare have dealt with these problems, whether converting to Christianity or deciding to accept that sleep paralysis might kill them (a sobering thought), doctors have not helped any of them. Despite how frequently such sleep paralysis visitations occur, both on a global and individual level, and how negatively it has impacted lives, physicians and therapists seem content to respond to their pleas for help with "it's just sleep paralysis" and don't provide them any relief.

So is it really sleep paralysis or is it something else? Although Kate A. explains her experiences rationally, she does state, "you can't put logic onto liminal situations." The fact that making the "positive lifestyle changes" their doctors suggested did absolutely nothing to stop the traumatic visitations for these people is disconcerting. In some cases, it's contagious, as some who suffer from it have actually passed it on to others. Are these apparitions nothing more than a sleep disorder, mental illness, or as Stephen P. speculates, could they be the result of the theory that we reside in multiple dimensions?

The most troubled person in The Nightmare is easily Chris C., who seems to have had the most negative and persistent experiences with sleep paralysis, which probably results in his attempts at humorous storytelling and his clearly fatalistic attitude. "It will kind of learn how to adapt to you. If you try to avoid it, it will find you and it will make it happen somehow," he says. Considering the lack of resolution for most of these people, his statement might be the scariest thing in all of The Nightmare.

The debate over whether or not horror films are sexist - or even misogynist - continues to rage, even as an increasing number of both male and female filmmakers subvert well-known tropes like the Final Girl or the Scream Queen. But despite what deluded GamerGate defenders might have you believe, sexism and misogyny are real, even if the narrative worlds that populate horror films are not. WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD!

At first sight, Ryan Gosling's directorial debut Lost River, might appear to be just another in the line of films focusing on a young, white, male protagonist. Iain De Caestecker, who portrays Bones in the film, is a dead ringer for a younger Gosling, especially in films like Half Nelson or Drive: short, dirty blond hair; white T-shirt and jeans "uniform;" and that intense but laconic stare.

As Lost River progresses, however it becomes apparent that the plight of the female characters is far more urgent and frightening. Bones's mother Billy, played by Christina Hendricks, takes a job as a cocktail waitress at a strip club in order to support her two kids and keep her grandmother's dilapidated roof over their heads. Neighbor Rat (Saoirse Ronan) is the caretaker for her own mute and damaged grandmother (played by horror legend Barbara Steele), a woman who is so unable to deal with her present precarious situation that she watches a videotape of her own wedding on 24/7 repeat.

Although Bully (played by an extraordinarily nasty Matt Smith) has an unexplained but explicit vendetta against Bones, the thrust of his hatred is wielded against Rat because he knows it will hurt Bones even more. Bully offers to give Rat a ride home from a local gas station convenience store, and even lets her sit in the makeshift throne on the back of his convertible, but it's a pretext for future malice. When he asks about her pet rat Nick, his voice and eyes are soft, but these are a mask for his real purpose: prying into her sex life in a way that belies his desire to exert control through violence. When he kills Nick, it's a symbolic rape.

Billy's plight is more obvious. In order to make payments on her home, she must submit to the whims of bank manger Dave (an intensely lecherous and repulsive Ben Mendelsohn), who swears profusely and comments that she's "a beautiful woman," neither of which are germane to her financial troubles. (It's also intriguing to examine how the recent arc of Hendricks' Mad Men character Joan feeds into this narrative.) Dave convinces Billy to accept a job at a bizarre burlesque theater he manages, one in which a live audience watches as women are butchered and brutalized on stage. It's all theater, with fake knives and fake blood, but their delight is obvious.

More disturbing are the underground rooms in which women are encased in translucent plastic, body-shaped chambers so that men can enact their fantasies upon them without actually touching them. Billy seems hesitant to embark on this employment path, even though Cat, the main performer, assures her that the money is good and that as long as the chambers are locked, the women inside are safe.

Later, Dave continues to exert his own control over Billy by warning her that she cannot bring Frankie to work with her because it's not "sexy" and then insisting on driving her home. He asks if she's going to invite him in and then says he has a "problem": he likes to fuck and bad bitches make him crazy.

At no point do Dave or Bully explicitly state that they want to rape either Billy or Rat. But the threat is palpable. Any woman who's been sexually assaulted knows this. Women who've narrowly escaped a sexual assault will also recognize the signposts. With no witnesses it's her word against his. Rapists know this and they manipulate and isolate their victims, choosing their words carefully in order to twist the situation to their own advantage.

While the dreamlike world of Lost River is a fiction, the hopeless situations that the women of the film are faced with are not. That's more frightening than any horror movie. Refreshingly, both women escape their fates through their own actions; they are not saved by the male characters. Despite its uncomfortably accurate portrayal of the ugly world we live in, Lost River suggests that all is not lost, after all.