Twin Peaks: Funny Ha-Ha or Funny Peculiar

Some viewers have had their patience tested by the slow pace of Twin Peaks' new season, but something is always lurking around the corner.

Read More

Some viewers have had their patience tested by the slow pace of Twin Peaks' new season, but something is always lurking around the corner.

Read More

Demdike Stare's collages of sound and imagery provoke responses akin to nightmares.

Read More

Mark Duplass's Creep brings the found footage horror film to the next level.

Read More

Although horror films and TV shows are experiencing a major surge of popularity right now, there’s yet another avenue available for artists to evoke fear and dread in people: music videos.

Granted, music videos might seem less significant now than they were in the 1980s and ‘90s, two decades which are usually considered their heyday, but they are still being produced, as anyone who as a Good Life gym membership can attest. Both the US and Canada still hold awards ceremonies with the words “music” and “video” in the title (MTV Video Music Awards and MuchMusic Video Awards, respectively), and although music videos might not make or break a band the way they used to, their existence is still part and parcel of the mainstream music industry.

But what about bands who aren’t part of the mainstream? Take for example, Portal, an Australian band fusing death metal and black metal (yes, they are distinct subgenres). Like their more sonically conventional brethren Ghost, the members of Portal keep their identities hidden; “band members don suits and executioners’ masks save for vocalist The Curator, who wears a huge, tattered wizard’s hat that obscures his face.” Portal is a band who is not content to have their image overshadow their sonic qualities; PopMatters writer Adrian Begrand astutely observes that their music is “truly friggin’ terrifying.”

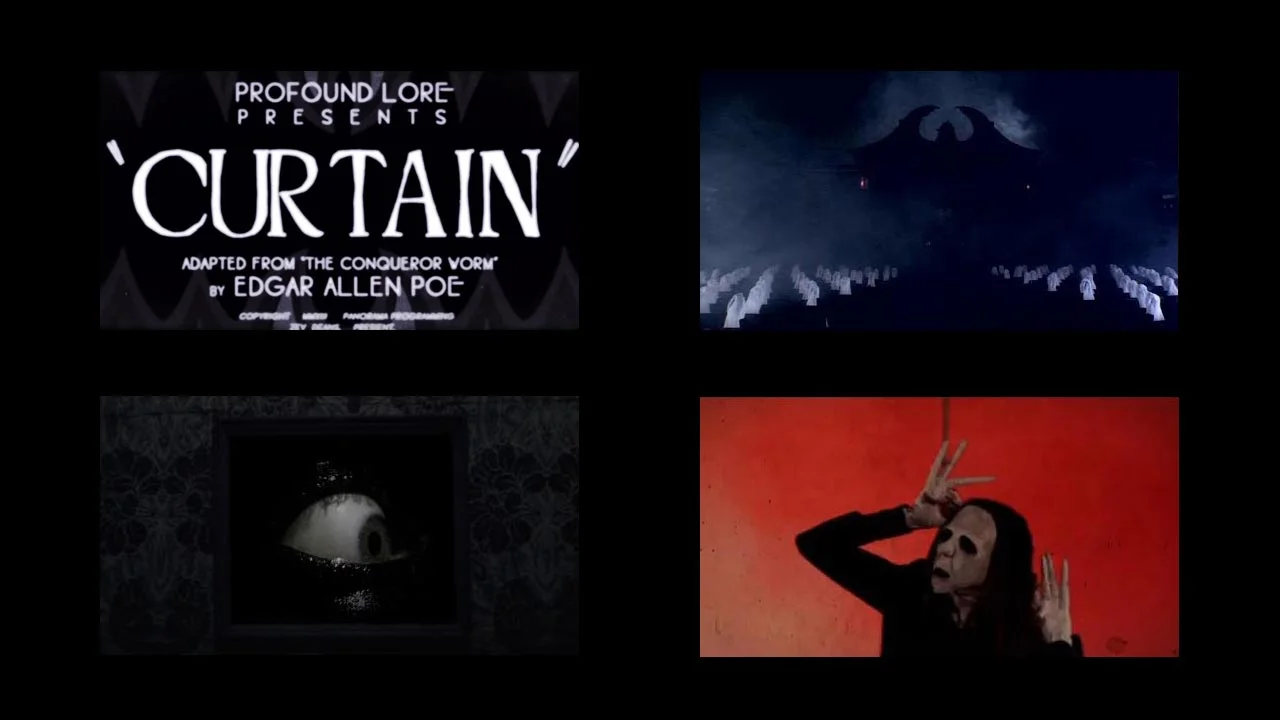

This is the kind of build up that leaves horror aficionados begging for more. Enter director Zev Deans, who created a bona fide horror show for “Curtain,” a track from Portal’s 2013 album Vexovoid.

Some decidedly retro-looking opening titles announce that the video is adapted from the Edgar Allen Poe poem, "The Conqueror Worm." While the word “conquering” implies a larger than life hero, the actual size of a worm is quite small when compared to that of a human being. This is, of course, the cruel twist of mortality: even the mightiest will eventually die and be consumed by the lowly worm.

Deans has captured the essence of Poe’s words in a remarkable way in his video for “Curtain,” making the titular worm into a sort of Gothic Kaiju by the end. One wonders what Poe himself would have thought of this video or if anything resembling its unforgettable visuals was terrorizing the inside of his skull while he wrote his poem. This is easily one of the more unsettling, if not outright frightening, music videos you’ll ever see.

Don’t try to figure out what The Curator is saying; just watch and listen.

No doubt that Portal’s intensely grim, demonic sound makes the perfect accompaniment to these images, but even watching the video without sound is a disquieting experience (to say nothing of hearing “Curtain” without any visual aids).

It’s worth noting that the imagery within, despite being disturbing, does seem inspired by other things from the horror canon like Ringu, Hellraiser, The Exorcist, Curtains, and Coppola’s Dracula (itself inspired by silent horror films), not to mention the videos Adam Jones directed for the band Tool. Yet somehow, Deans combines these elements in a fresh way, one that evokes rather than imitates.

Although the video for “Curtain” is just under six minutes in length, those looking for new ways to scare audiences without crappy CGI should look to Zev Deans for inspiration.

If you’ve seen films like The Road or We Need to Talk about Kevin or the more recent Nothing Bad Can Happen, you likely know that there is bleak and then there is black-hole bleak, films that are so dark they make you lose faith in humanity. When bleak films have classic horror elements such as supernatural entities, classifying them as “horror” is easy enough. What happens, however, when they are firmly set in reality?

1986’s Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is considered a “psychological horror film” by Wikipedia. Tony, directed by Gerard Johnson in 2009, is described as “British social realist comedy/drama” on Wikipedia. It’s also based on a serial killer, one Dennis Nilsen. Although there are definitely comic elements, it’s a nasty bit of work, one with enough gore and grime to make you feel like you need ten hot showers.

So where do we draw the line? Is realistic horror somehow less horrific than vampires, zombies, or masked serial killers who can’t be killed? That scene in The Road where Viggo Mortensen’s character discovers the people in the basement is burned forever into my brain as a genuinely horrifying moment. Most of the time I spent watching We Need to Talk about Kevin my stomach was in knots because I knew something terrible was going to happen and that no one would believe Eva when she tried to warn people about Kevin.

Nothing Bad Can Happen consists of a series of increasingly awful scenarios set into motion by Benno (an adult) to torment Tore (a teenager). If you’ve seen that film, you’ll remember the cat scene, the garbage scene, or the scene in the trailers. How are the egregious acts depicted NOT horror?

These kinds of movies often get tossed into the “genre” category which is a polite way of saying “we know this movie is scary but we don’t know what the hell to do with it.” Not that movies like the ones I’ve mentioned need to be categorized to be good (or effective), but imagine how difficult it is to market these or get them distributed.

That’s the real problem. These are the kinds of movies that tend to be ignored, vilified, or forgotten altogether. Although We Need to Talk about Kevin snagged a BAFTA for Tilda Swinton, The Road received only limited release and its box office returns were only slightly higher than its budget. Nothing Bad Can Happen received both boos and cheers at its Cannes premiere, and to date has earned a paltry $4K worldwide from its purported half-million budget.

No matter the budgetary limitations, these kinds of frightening, unclassifiable films will continue to be made, but in a cinematic landscape dominated by blockbuster franchises, it’s become increasingly difficult to get them financed. By opening up the horror landscape to more varied fare, from both critical and audience perspectives, we can, however, ensure that that they don’t get lost in the shuffle and that those who want to make them are able to do just that.

Count Dracula, 1977

When I was younger, lots of things terrified me. Not all of those things were intended to be scary, either. It's one of those burdens that some kids are just forced to bear.

One of my earliest fears was of vampires, inspired by a BBC TV production of Bram Stoker's Dracula starring Louis Jourdan. That two-part miniseries forced me to sleep with a crucifix, a rosary, AND a Bible for at least two nights. A few years later, the trailer for Halloween III terrified me to the point that I had to change the channel when it came on. Horror movies haunted me for years and were responsible for many sleepless nights and panic attacks.

At one point, it was the clown puppet in Poltergeist, then Pazuzu in The Exorcist. An unexpected screening of The Gates Of Hell at a friend's house when I was 15 was particularly scarring. When I was in my twenties, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was so terrifying that I couldn't get through it the first time around and had to wait a couple of decades to work up the courage again. 28 Days Later, Signs, Jeepers Creepers, The Descent, À l'intérieur, Insidious... all of these thrust me into varying levels of fright, from heart palpitations to openly weeping from fear.

Most recently, it was the movie February that got under my skin. Even though I saw it during TIFF in the daytime, it stayed with me in the way that all effective horror films do: you think of them in the middle of the night when you wake up to get a drink of water and get the actual creeps.

Being completely and thoroughly scared throughout an entire movie is rare. This isn't just an empirical perspective; good horror filmmakers know how to layer jump scares, creeping dread, and/or gut-churning gore in ways that are calculated to shock the senses at key points. Yet, as every hardcore horror film fan will admit, it becomes harder and harder to find movies that will completely scare the hell out of you. Part of this is due to becoming older and wiser; part of it is due to desensitization.

For many, the pop cultural glut of zombies has rendered them not only not scary, but annoying. In the last decade alone, we've seen countless movies and at least five different TV series about zombies, one of which is Fear The Walking Dead, a spin-off of The Walking Dead, a show whose ratings have increased every year since 2010. Zombies, it would seem, are everywhere. So are they still scary?

One of the most frequent complaints about The Walking Dead (besides people hating on poor Carl Grimes) is that there aren't ENOUGH of the titular characters on the show. Season Two was derided as "The Talking Dead" and when compared to the more recent seasons of the show, it feels admittedly underwhelming. At this point, people seem to love zombies, but it's hard to tell if they're actually scared of them.

February, 2015

So what do people want now? Do they want to be scared, or do they just want to revel in the gore and blood? At what point does fear transition into the vicarious thrill of rooting for the good guys? The pendulum will always swing into the other direction and despite the overwhelming amount of zombie pop culture interpretations available, there are some who are taking it into different and interesting directions, as shown by the TV show iZombie or the recent comedy Life After Beth.

And there are always new versions of old ideas. For example, there seems to be a renewed interest in Satanic or occult-themed movies and TV shows, like February, for example, which is far more disturbing than any of the recent found footage possession films I've seen.

Since this new iteration of horror - the lurking danger of demons - hasn't yet been done to death, there are still plenty of opportunities for the discerning horror fan to seek out different ways to get scared. At least until the next trend comes along.

Have you seen The Pact? You'd be forgiven if you skipped over this 2012 horror release due to its generic title and bland poster art. Then again, you'd be missing out on a truly effective chiller.

Nicole Barlow is tying up loose ends after her mother's recent death. She's a recovering drug addict so when she doesn't return phone calls, texts, or emails for a 24-hour period, her sister Annie blames it on a relapse. Then Annie finds Nicole's cell phone in the same closet in which she and her sister were banished when they misbehaved as children. When their cousin Liz vanishes in the middle of the night, Annie starts to suspect that something more sinister is at play.

The Pact uses simple but arresting imagery to startle the viewer. All of the visuals make up a vital part of the narrative; there are no throwaway scares here. Although several of these images continue to haunt the viewer long after the credits have crawled across the screen, what is most important to the story in The Pact is the house.

Many haunted house films tend to be set in old, crumbling Victorian or Gothic mansions which, let's face it, are pretty ominous and imposing on their own. But The Pact isn't exactly a haunted house movie. What makes the film unique is the utterly ordinary quality of the home that resides at the center of the terror. The opening of the film is a slow tracking shot through a narrow hallway that is covered in busy, 1980s style wallpaper. It doesn't seem that creepy at first, but it soon will be.

From the beginning of the action in the film, the house has a distinctly unnerving presence. Filmmaker Nicholas McCarthy uses a specific color palette of yellow and black through the set design and the camera filters, which casts a shadow of queasiness over this very believable place.

Many homes depicted in horror films don't appear real: they're too modern, too clean, too perfect. This is not the case with the Barlow home in The Pact. The furniture is old and threadbare and the carpet and flooring are dingy. Overall, the Barlow home is cluttered and claustrophobic. It looks like the house of someone who recently passed away unexpectedly. It looks real.

There is also a preponderance of religious iconography in the home which suggests that someone in the home was either deeply religious and that such artifacts would ward off some kind of evil. Again, it's subtle but effective; Mrs. Barlow's religious convictions are not mentioned specifically by any of the characters. We only see it in visual terms.

It isn't just that "bad things" happened in the Barlow home, in the form of Mrs. Barlow's abuse of her daughters. It's that something evil literally does reside in this home, in a hidden room that Annie did not know about until now. This isn't the typical "pull the book from the shelf, and it reveals a secret passageway" kind of hidden room. It has been dry-walled and wallpapered over and only shows up in the original blueprints of the house.

Not only does the house in The Pact look like something out of a nightmare - which is further reinforced by that same slow tracking shot through the hallway comprising the bulk of Annie's nightmares in the film - it actually houses a palpable evil in the form of Erik Barlow, who is a serial killer.

Perhaps the film's unimposing title and seemingly uninteresting poster are both perfectly suited for a film that's a lot scarier than it might initially appear.

Many film fans and filmmakers have recently expressed a desire to go back to the basics, aesthetically speaking, insisting that what you don't see in a horror film is scarier than anything conjured through CGI. They argue that smaller budget films are often more effective than tentpoles because financial restrictions force the filmmakers to be creative when devising ways to provoke an audience into fear.

A beautiful example of this theory in practice is Mike Flanagan's 2011 film Absentia. It treads some of the same ground as Flanagan's more recent Oculus, in which a family is tormented over the years by a haunted mirror. In Absentia, the object in question is a tunnel connecting a Southern California subdivision to a nearby park.

Tricia's husband Daniel vanished seven years ago. No body was found, and after much anguish, she decides to have him declared dead "in absentia" for both legal and personal reasons. Her sister, Callie, a former runaway and drug addict, visits Tricia to help with the process of moving on and moving out of her apartment to begin again. Tricia his also pregnant, and offers no clues as to the identity of her unborn child's father, but she has embarked on a tentative relationship with Ryan, the cop in charge of Daniel's missing persons case.

Just as things seem to be progressing in a positive direction, Daniel shows up, both physically and psychically damaged, with only vague, nonsensical ideas of where he's been for the better part of a decade.

So much of Absentia's frightening aura comes from unreliable narrators: Tricia because she has lucid dreams of a black-eyed, enraged Daniel; Callie because, although she claims to be sober, she's still surreptitiously using drugs (though we don't see her in the act); Daniel because he speaks of a thing in the walls that's trying to get him.

When awful things start taking place in Absentia, we don't actually see them, only hints of them. Sounds and movements out of the corner of the eye; people who appear out of the shadows but aren't really there; a homeless man in a tunnel, begging for help and raving about nameless creatures. Such occurrences could easily be explained away.

There are a lot of typical problems in Absentia: flyers for missing people (including Daniel) and pets are pasted on telephone poles and there have been a series of petty burglaries in the neighborhood. We see these things so often they barely register with us anymore. Then there are the more personally upsetting, but still commonplace misfortunes: unpaid bills, legal paperwork, troubled marriages, broken families, single motherhood and addiction. Finally, there are fantastical issues that plague the characters: the alleged existence of a city underneath the ground, where humans are kidnapped by a monster with skin like a silverfish.

In Absentia, all of these events are connected. Furthermore, the gravity of these various tragedies shifts from banal to otherworldly and back again before the characters-or indeed the audience members-are aware that such a shift is taking place. Trying to explain it to someone who can't or won't understand - much like Callie does with Tricia - is met with disbelief. "It's easier to embrace a nightmare," says Tricia, "than to accept how stupid - how simple - reality is sometimes."

But what if the answer is both a nightmare and reality? Much like the tunnel that connects the characters to the horrible thing that holds sway over them, Absentia occupies that liminal space between reality and unreality. Was the silverfish crawling in the sink just a bug or a harbinger of something worse? Is Daniel a paranoid schizophrenic? Did Tricia imagine his appearance or was he truly there? Was Tricia spirited away by the thing in the tunnel or did she cut herself off from the grid to start her life over again?

There's a scene in the film where Tricia and Callie are turning out the lights to go to bed, and Callie hears a noise. The camera cuts to a shot of Tricia, staring into the black nothingness of her living room. But instead of a void, there's a monster in there that literally takes her away. We never see the monster, but Tricia's absence is as palpable as its presence. Later Tricia scrawls, "beware the things underneath" on a note she leaves for Ryan.

This liminality is what makes Absentia genuinely terrifying. It feels like the events in this film could happen to anyone, even us. If that happened, then who would believe us? We are all unreliable narrators of our own lives in a way; our experiences and prejudices color our perceptions of what we see. We can never totally be sure of our own objectivity and that sure scares the hell out of me.