My Dream Is On The Screen: “Fire Walk With Me”

Part of what made Twin Peaks the series so captivating was the way it played with tropes and expectations. The heightened artifice of the acting style of the cast along with the show’s soap-opera like narrative created a distance between screen and audience, but it also allowed viewers to succumb to their emotions in a way that more straightforward dramas, which seem to demand a kind of mute respect, do not. The horror elements of the show---rape, incest, mind control, alternate dimensions, the manifestation of pure evil---seem even more terrifying by comparison. The 1992 film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me continues to exploit this dichotomy.

It opens with credits set against the fuzzy static of a TV screen and Angelo Badalamenti’s narcotic, jazzy score. When the camera pulls back it is revealed that we are indeed watching a TV, but before we can get our bearings a hatchet comes down and smashes the TV set to bits while a woman’s scream interrupts the music. It seems that the fourth wall has been broken (twice, if you account for the screen-within-a-screen aspect), and Lynch continues to remind us of that tension between the real and the surreal throughout the course of the film.

For example, FBI Chief Gordon Cole’s office is decorated with a trompe l’oiel wall of forest landscape behind him, a precursor to the scenery in Twin Peaks itself. Cole also hires an interpretive dancer named Lil to greet FBI agents Chet Desmond and Sam Stanley at the airport. Desmond subsequently quizzes Stanley on what Lil’s facial expressions, gestures, and clothing signify. These are layers of semiotics that Lynch is not only adding, but also satirizing.

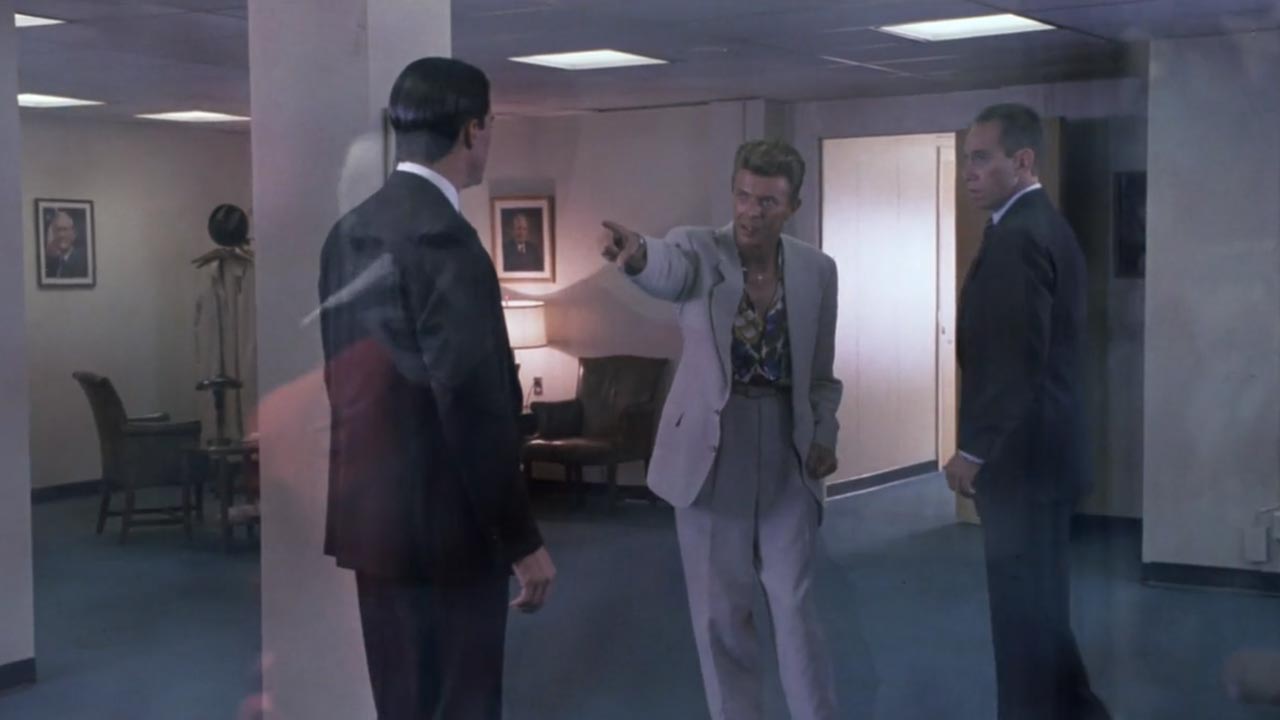

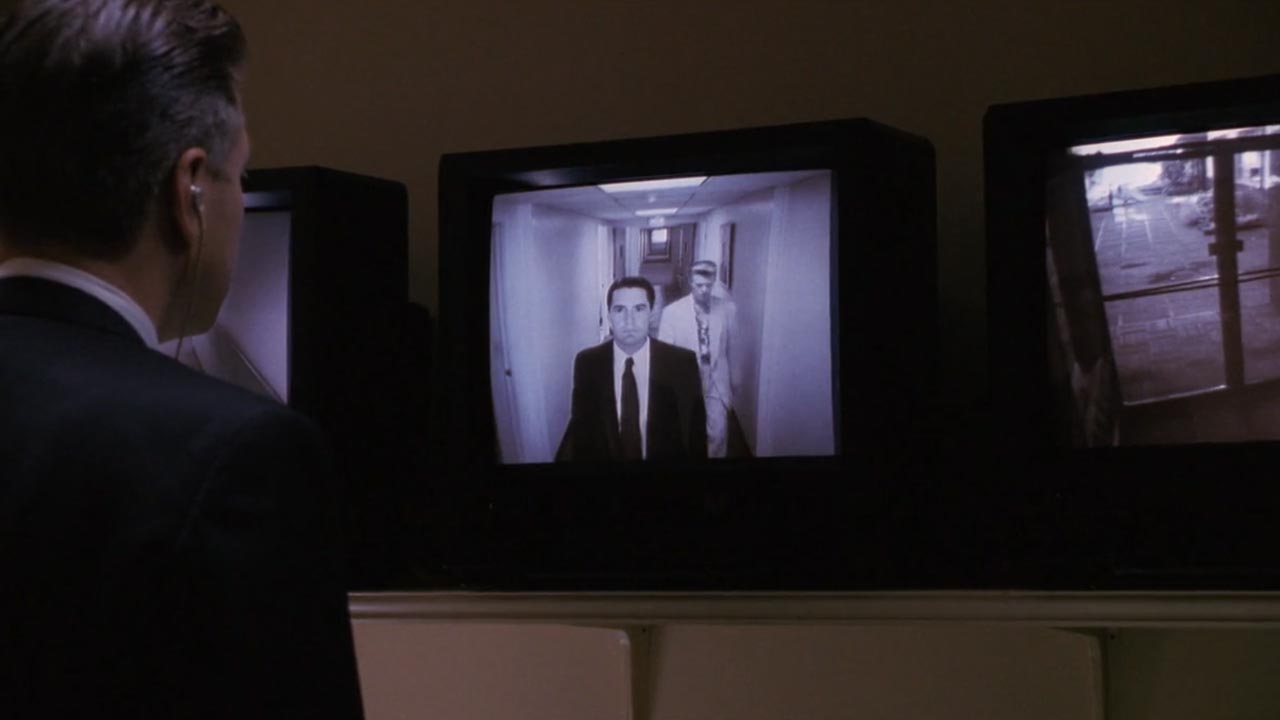

A short time later in the film, missing agent Phillip Jeffries appears at the FBI headquarters in Philadelphia. Or does he? After Agent Dale Cooper expresses concern to Gordon because of a dream he told him about, we see Cooper going in and out of the hallway and the surveillance room full of TV screens. At one point Jeffries appears behind him and then walks into the office and begins to speak to Gordon and fellow agent Albert Rosenfield. His speech is interrupted by the blue static from the opening credits overlaid upon strange visions of a dingy room inhabited by the Man From Another Place, Mrs. Tremond and her grandson, BOB, and others.

Then Jeffries disappears again, but not before we hear him say, “We live inside a dream.” Rosenfield calls the front desk and says, “He was never here,” but a subsequent scene shows both Cooper and Gordon looking at the surveillance footage on the TV which clearly shows Jeffries behind Cooper in the hallway. “He was here,” says Cooper, as if Jeffries’ presence can only be confirmed by his appearance on the TV screen.

It isn’t difficult to guess why, after years of sexual abuse by a mysterious man (who, it should be noted, crawls into her room via the “screen” of her window), outgoing, popular, and seemingly wholesome high school student Laura Palmer turns to cocaine and prostitution. Her double lives collide when she starts to suspect that BOB, who she tells her friend Harold “has been having me since I was twelve,” may also be her father. Soon the film will reveal how these seemingly disparate and possibly cross-dimensional worlds are connected through another type of screen: a framed portrait.

Mrs. Tremond and her grandson appear in the parking lot of the Double R Diner with a framed portrait of a room. The scene is overlaid with that same blue static we saw earlier. The portrait shows a non-descript room with a door that is slightly ajar. Mrs. Tremond tells Laura “this would look nice on your wall” while her grandson whispers that “the man behind the mask” is “under the fan now.” Laura becomes alarmed and runs home, portrait in hand, to look for BOB, who she assumes has been stealing pages from her secret diary. She finds BOB in her room, but when she runs from the house in terror, she only sees her father leaving.

Later, after dinner and a disturbing scene with Leland/BOB that clearly rattles Laura, she hangs the portrait on her wall. The film cuts from a shot of the portrait on the wall to the actual room; it has now become a portal between these two “worlds.” The camera tracks in and Mrs. Tremond is there, beckoning the viewer towards another room with another slightly ajar door. Then the familiar red curtains appear along with the black and white tiled flooring.

Dale Cooper walks in and after seeing Teresa Banks’ missing ring in the hands of The Man From Another Place, he addresses the camera, saying, “Don’t take the ring, Laura.” Here we are simultaneously Laura Palmer and the audience watching Laura Palmer dreaming. Laura sees a bloody Annie Blackburn in her bed telling her that “the good Dale is in the Lodge” but it isn’t until Annie disappears and Laura notices that Teresa’s ring is in her hand that she becomes scared. She climbs out of bed, opens the door, and then looks back to see that she is now inside the portrait on her wall, looking through the door. From within the portrait, Laura watches herself sleep.

Leland Palmer has similar breaks with reality when his own secret life as BOB starts bleeding through. The One-Armed Man (a.k.a. MIKE, a.k.a. Phillip Michael Gerard) tries to warn Laura that BOB is her father while shouting through a truck window and wearing Teresa’s ring. The confrontation, which has the outward appearance of a particularly upsetting road rage incident, has a deeper meaning, one which provokes Leland to remember things.

With no indication that Leland is having a flashback, the scene cuts to a photo of Teresa Palmer in Flesh World magazine, then a motel sign, and then Leland in bed with Teresa, saying, “You look just like my Laura.” We hear Laura shouting “Dad!” and Leland looks to the side before the camera cuts back to the present, with Leland still in the car. The following exchange between Laura and her father is shot through the front windshield of the car, yet another screen which underscores the various layers of reality of not only this particular scene, but also the lives of these two characters.

Another seamless flashback transition occurs when Leland thinks back on when he was supposed to have a tryst with Teresa and her two friends, but realized that one of the two friends was his daughter. He sees Ronette Pulaski and Laura through the slightly ajar door of the hotel room and then decides to leave, telling Teresa that he “chickened out.” Both Leland and Laura discover things via open doors, albeit in different contexts and at different times. By shooting Leland’s flashbacks and Laura’s dream with similar lighting and with nearly invisible editing, Lynch shows that in a way, time has not only caught up with these two characters, but also become meaningless. The past is the present is the future, with the latter represented by the appearance of Annie Blackburn and Dale Cooper in Laura’s dream, two characters who at this point in the movie prequel, are both unknown to Laura Palmer herself.

At the end of the film, Leland/BOB forces Laura to look into a mirror, where she sees her face transform into BOB’s, another instance of frames becoming doorways. Yet before Laura is killed, the angel who has disappeared from the portrait on Laura’s wall reappears to her, and again later in the Black Lodge. Earlier in the movie, Laura had suggested to Donna Hayward that if you fell into space “the angels wouldn’t help you because they’ve all gone away.” At the end, although Laura has been killed by BOB, she finds some kind of peace. Or does she? Does Laura truly see the angel or does her desperate need for happiness create an illusion?

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me presents many questions but does not answer them conclusively: What is a dream and what is reality? And can Laura Palmer, or any of us for that matter, truly tell the difference?