If Amelia is perfectly sane in The Babadook, then she is perhaps worse off. The laws of our universe as we know them do not accommodate spectral, pop-up book enthusiasts who can manipulate reality and possess single mothers. The world proposed by a literal reading of The Babadook is near unthinkable. It is one in which we are wrong about everything and no one is safe. It is a reality that looks exactly like insanity.

In volume three of his Horror of Philosophy series, Tentacles Longer Than Night, Eugene Thacker says that it is the space between the definitive answers of sanity and insanity - a state which he terms fantasy - that horror thrives. Lovecraft and Poe, whose works make up the bulk of Thacker’s analysis, were masters of this balance. The author points to the introduction of Poe’s The Black Cat and Lovecraft’s The Shadow Out Of Time as pinnacle examples of this trope. Each story begins after the subsequently described events take place and the narrators specifically tell their readers that, given the unlikeliness of their recountings, it is quite possible they are insane.

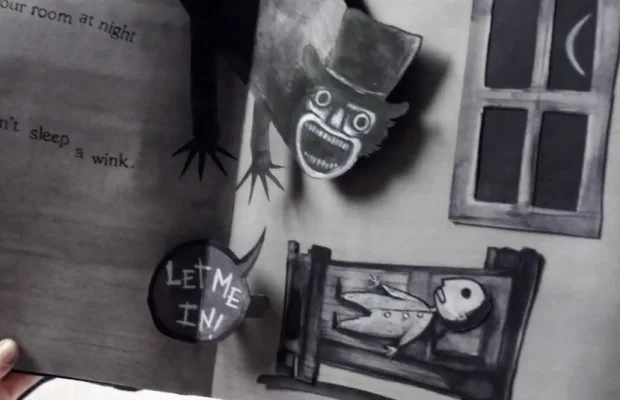

In stories that evoke the question of a sane narrator, regardless of the medium, the question of reality is integral to the stakes and a key ingredient in the horror. It is the mark of a master, I think, when done properly and left unresolved. Either side – clear minded or off the rocker – provides an anchor from which an audience can navigate the supernatural events of a given tale. When those anchors are taken away, like they are in The Babadook, we are left to drift in the terrifying moments that make up the present. Here in the sea of uncertainty, where we live daily life, we can access something more terrifying than an unmapped reality or a broken brain: we face the human frailty contained in the thought that an explanation can’t save us from our present circumstances.