Hannibal Rewatch Diary: Empathy and Aria in 'Apéritif'

It’s dogs.

In Apéritif, the first episode of Hannibal, empathy is served from the opening moments to the final shot.

Read More

It’s dogs.

In Apéritif, the first episode of Hannibal, empathy is served from the opening moments to the final shot.

Read More

In the advent of ground-breaking true crime shows like The Jinx and Making a Murderer it seems utterly bizarre that a show like Crime Watch Daily exists.

For starters, each episode opens like Inside Edition, the TV show equivalent of those annoying click bait Buzzfeed headlines that clog your Facebook feed with crap like “You won’t believe what happened when this man ate a cheese sandwich!” The barrage of “if it bleeds, it leads” style headlines on Crime Watch Daily provide viewers with very little useful information about actual crime, relying instead on grabbing ears and eyeballs with whatever salacious copy they can conjure. At least you can click on clickbait headlines; you have to sit through an entire episode of Crime Watch Daily to get to the “good” stuff.

It’s bad enough that the Internet is crammed with this kind of junk; do we really need it on our TV screens as well? It’s a relevant question since the Crime Watch Daily set virtually indistinguishable from the ones used by shows like Entertainment Tonight: all glass, chrome, sparkling lights, and giant flat TV screens. The set also looks like a super close up photo of microchips, which ironically only serves to further highlight the distinction that this is Not The Internet.

The idea that a daily TV show would be able to keep up with crime stories in real time as they develop – a market the Internet and 24-hour news channels have cornered – makes the existence of Crime Watch Daily an anomaly in the first place. If they were reporting on the kinds of things that viewers need to know about crime on a daily basis, perhaps an argument could be made that they provide a vital service, but they don’t.

It’s true that we take risks every time we leave the house (or in the case of a home invasion, while we’re there). Depending upon where we live or what kind of job we have, we could encounter a lot of crime: mugging, shooting, stabbing, kidnapping, or sexual assault. These kinds of risks, however, are already covered by local news programs and crime data maps that are available on, you guessed it, the Internet.

Note that I’m not implying local news stations always do a bang-up job reporting on the kinds of crimes we might encounter, but they are at least more qualified to give us a microcast of what’s going on around us than a national program like Crime Watch Daily. The show does have a segment called “Crime Watch Local,” but it only airs weekly, competing with 30 to 40 other minutes of the show’s airtime; therefore, it would be impossible to cover every “local” corner of the United States.

Crime Watch Daily doesn’t even provide any tips or tricks for how to avoid crime, focusing instead on just telling us about it without giving us any insight into what the crime could mean to the viewer on a personal level or what it means to crime in society as a whole. In fact, the show has two specific segments that seem to have been created purely out of some need to make fun of others. “Bad Seed of the Day” and “CrimeTube” are, respectively “a weekly segment profiling a particular criminal and the crime they committed” and “a daily segment… featuring videos of criminal acts, sting operations, police pursuits, and footage of law enforcement activity culled from public doman security camera, traffic camera, and police dashcam footage." Yeah, we have that second thing already; it’s called YouTube.

Sure it might give us a feeling of schadenfreude to witness criminals being caught in the act, but does that serve any real purpose? No, it seems that Crime Watch Daily is merely interested in WATCHING crime, not examining it, not trying to prevent it, not helping viewers get a more profound understanding of it. It’s a spectator sport that takes real tragedies and repackages them into glossy, bite-sized chunks of sugar, providing a quick fix of empty calories.

There is a certain element of fear-mongering on Crime Watch Daily, which feels carefully scripted to highlight the lurid details and the emotional fallout of the crimes it depicts, but the show doesn’t evoke empathy in the same way that seeing a grieving family member at a press conference or being interviewed at a crime scene might. It’s like a ginned-up version of fear that makes people feel like they know what’s going on even though Crime Watch Daily only provides limited information, the kind of thing that people might use to justify racism, classism, sexism, and the intersection of all three.

Crime Watch Daily is fear mongering without the fear, replaced instead by self-righteousness. That’s truly scary.

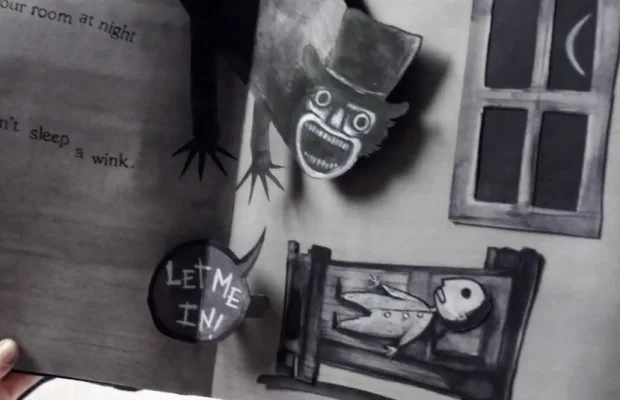

What is worse: sanity or insanity? The question is at the centre of supernatural horror, and while the answer seems obvious from the experience of a reader (likely sane), things aren't so clean cut in the realm of lucid nightmares. Put yourself in the shaking boots of Amelia, the tortured mother from The Babadook, for instance, and then ask yourself which mental paradigm you would prefer.

Aided by the unreliable narrator device that is typical of horror genre fiction, supernatural elements in stories like The Babadook thrive on the balance between the opposing worldviews of unbridled imagination and a strange reality. Throughout that film, the audience is given numerous hints that Amelia’s experience with the titular evil entity is simply a figment of her imagination born of insomnia, trauma and the stress of having a difficult child who builds weapons as a hobby. Stuck in her point of view, however, we are shown the Babadook as it appears to her: an increasingly real threat to the life of her son.

As viewers of Amelia’s struggle we are given two options on how to explain the film’s conflict. Is Amelia sane or insane, and which is worse? If she is insane - and the film’s ending is certainly open enough to suggest that she is being tortured by her mind - then the struggle exists solely within her home. The stakes are still very high, since an expressionist reading of the film forces you to accept that Amelia is trying to stop herself from a powerful urge to murder her son, but they are isolated. The same can’t be said if we accept a literal reading of the events.

If Amelia is perfectly sane in The Babadook, then she is perhaps worse off. The laws of our universe as we know them do not accommodate spectral, pop-up book enthusiasts who can manipulate reality and possess single mothers. The world proposed by a literal reading of The Babadook is near unthinkable. It is one in which we are wrong about everything and no one is safe. It is a reality that looks exactly like insanity.

In volume three of his Horror of Philosophy series, Tentacles Longer Than Night, Eugene Thacker says that it is the space between the definitive answers of sanity and insanity - a state which he terms fantasy - that horror thrives. Lovecraft and Poe, whose works make up the bulk of Thacker’s analysis, were masters of this balance. The author points to the introduction of Poe’s The Black Cat and Lovecraft’s The Shadow Out Of Time as pinnacle examples of this trope. Each story begins after the subsequently described events take place and the narrators specifically tell their readers that, given the unlikeliness of their recountings, it is quite possible they are insane.

In stories that evoke the question of a sane narrator, regardless of the medium, the question of reality is integral to the stakes and a key ingredient in the horror. It is the mark of a master, I think, when done properly and left unresolved. Either side – clear minded or off the rocker – provides an anchor from which an audience can navigate the supernatural events of a given tale. When those anchors are taken away, like they are in The Babadook, we are left to drift in the terrifying moments that make up the present. Here in the sea of uncertainty, where we live daily life, we can access something more terrifying than an unmapped reality or a broken brain: we face the human frailty contained in the thought that an explanation can’t save us from our present circumstances.