I Am Become Death: The Horror Legacy of “The Day After” and “Threads”

The Day After

The Day After first aired on ABC on November 23, 1983. As an avid TV watcher, I recall the hype that surrounded the broadcast. I also remember being fairly underwhelmed by the movie itself. That’s not to say that I was unafraid of the prospect of nuclear war; I remember feeling overwhelmed by the idea that I, along with everyone and everything I knew, could be vaporized in an instant.

The nuclear war film that actually terrified me was Threads, a British production from 1984. It evoked the uneasy feeling of “I really should not have watched that.” The image of a woman seeing a mushroom cloud and then urinating on herself out of fear struck me as both grotesquely comical and absolutely chilling. For years, that was the only thing I remembered about Threads, which loomed large in my mind as a quasi-horror movie.

There had been nuclear war/apocalypse films before 1983, but The Day After proposed something different: a realistic scenario of what might happen in the aftermath of a Russian nuclear attack on US soil. It was also something meant to attract the attention of a different demographic: those who had not yet been born during the first iteration of the Cold War or older folks who had perhaps chosen to forget what that time was like.

The Washington Post’s TV critic Tom Shales wrote about the film a few days before its premiere:

"Who should watch it? Everyone should watch it. Who will be able to forget it? No one will be able to forget it.

"Indeed, it could be argued that not to watch 'The Day After,' the ABC film about nuclear holocaust, would be a socially irresponsible act, considering the public fuss that has preceded the broadcast and the fact that the program itself has achieved the status of an 'issue'."

This kind of critical analysis immediately set The Day After apart from its predecessors. This was not another Airport movie or The Poseidon Adventure; this was gripping drama with a sociopolitical conscience.

Watching it 34 years later, The Day After is simultaneously better and worse than I recall. It opens with what looks like newsreel footage of pilots on a plane and some anachronistically uplifting, patriotic-sounding music. There are clichéd scenes of America: classrooms, parks, farms, sports arenas, parks, small towns, etc. Superimposed text informs the viewer of the various locations in and around the Kansas City, Missouri area; each one indicates how many miles apart they are from each other. We are introduced to a large cast of characters, none of whom seem to be connected except for the fact that they all reside and work in the area.

As we learn, they are all connected, not just as neighbors, but as Americans who will soon be suffering from the effects of a nuclear war. It’s a corny message that could have been strengthened by focusing on a smaller cast. With so many people to pay attention to, the characters feel like boiler plate ciphers: the friendly doctor, the caring nurse, the young woman about to be married, the army guy whose wife doesn’t want him to report for duty, the cynical science professor, the college kid trying to get home, etc. The film was intended to be a four-hour, two-night event, which could explain why some of the narrative threads and characters feel half-baked, but regardless, the film feels awkward and not completely engaging.

Visually, too, the film falters in this respect. While medium and wide-angle shots may have been intended to show accessibility to the universality of the characters and the grandeur of the landscape that would soon be decimated, The Day After often ends up looking like every other hour-long drama on television.

This is not always the case, however. The literal “calm before the storm” is portrayed well; a shot of a lone white horse running through a field is both pastoral and filled with suspense, and prefigures a similar scene in 2002’s 28 Days Later.

Additionally, there is a creepy quality to the various shots of residents standing around, in slack-jawed awe, as missiles fire into the sky.

As for the nuclear bombs themselves, ingenious special effects work renders these scenes quite unsettling.

The physical manifestations of radiation burns are far less convincing, however, which is surprising considering The Day After’s reported $7 million budget. The cast members sport bald caps and prosthetics, while scores of extras stumble around in tattered, bloody clothes, more resembling the zombies from the original Dawn of the Dead than anything else. This was partially intentional. As makeup designer Michael Westmore told the New York Times in 1983:

“Some of the survivors of Hiroshima had their eyeballs literally melted out of their heads. Even if we were doing a feature film, that would have been too strong to show. We wanted to create reality, but not horror. My purpose was not to make viewers sick.”

This didn’t prevent the film from utilizing actual photos of Hiroshima, albeit ones beefed up with special effects, such as when Jason Robards gazes at a ruined Kansas City.

What’s notable about this is that incredibly graphic footage of Hiroshima victims had already been utilized in another film, this one from 1959. Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour is no watered-down “duck and cover” affair, but it’s one with which few Americans outside of film scholars and hardcore cineastes were likely familiar.

Perhaps more effective is some of the dialogue in The Day After. A few days before Russia attacks the United States, Dr. Russell Oakes (Jason Robards) watches the news with his wife Helen and they ponder if this could actually happen, remembering their collective fear over the Bay Of Pigs when they were younger. Oakes tries to downplay the situation: “People are crazy but they’re not that crazy.” The next day, his colleague, a German doctor, expresses less conviction: “Stupidity has a habit of getting its way,” a sentiment that feels all too horrifyingly familiar in 2017.

This same difference of opinion is also found amongst the students at the local college. While watching the news reports, one young woman scoffs and dismisses it as “fantasy land.” An outraged young man gawks at her: “You think they’re making this up? You think this is War of the Worlds or something?” The exchange is not very different in tone from many current social media discussions about fake news.

Yet there are no “sides” taken in The Day After, despite the attempts of many to politicize the events of the film. Director Nicolas Meyer insisted that the answer to “who shot first?” remained ambiguous and felt a strong compunction to make the film, saying in his production diaries that “I cannot live with myself if I don’t make this movie.” This attitude went a long way towards convincing Jason Robards to star. “It beats signing petitions,” he reportedly remarked.

Did the film have an effect on public policy? Tom Shale mentioned that the film “may inspire [President Ronald Reagan] to say a few words on behalf of peace and coexistence.” According to a BBC 2 radio special, Meyer hoped that the film would deny Reagan a second term. It did not, but according to Reagan’s own diary, the film left the President “greatly depressed.”

As far as pundits were concerned, The Day After was “highly emotional propaganda for the antinuclear movement in this nation” and as one analysis notes, “[c]onservative organizations and newspaper columnists were predictably incensed by the perception that the movie was a liberal teaching tool.” From the same article: “However, at the time of The Day After many on the right also believed in the concept of a winnable nuclear war and advocated for civil defense in accomplishing such a victory.” It’s hard not to think of the line from the 1984 film War Games: “The only winning move is not to play.”

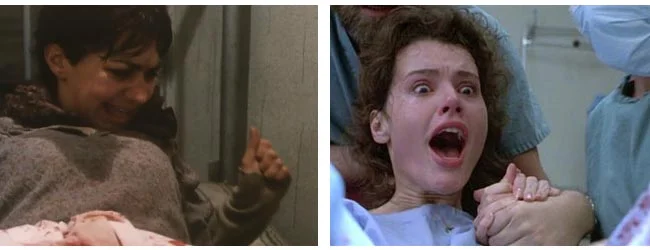

Although the UK production Threads aired less than one year later, many in the US did not see it until it aired in 1985, myself included. It contains many of the same tropes shown in The Day After—ongoing radio and TV news reports, an ignorant public, panic in the streets, grocery runs, pregnant women giving birth after the war begins, depictions of radiation poisoning and death— but the two films couldn’t be more different in tone and execution.

Threads

Threads was written by Barry Hines, a writer whose novels Kes, The Gamekeeper, and Looks & Smiles were all adapted to film by noted British director Ken Loach. This is a far cry from The Day After’s scribe Edward Hume, whose credits include Barnaby Jones, The Streets of San Francisco, and the 1973 film Sweet Hostage.

This kind of “kitchen-sink neorealism” is far more effective than the overwrought melodrama of The Day After. Despite the fact that Threads had a fraction of the production costs of The Day After (a reported $350K to $400K in US dollars), its effectiveness at evoking paralyzing terror is exponentially greater. Threads is an intimate and deeply affecting film thanks to naturalistic acting and dialogue and because Jackson and cinematographers Andrew Dunn and Paul Morris use mostly close-ups and medium shots. This is the case even when the film shows a series of fictionalized anti-war protests and rallies, scenes that feel shockingly contemporary despite the remove of several decades.

Like The Day After, Threads director Mick Jackson used a cast of mostly unknowns. Significantly reducing the number of cast members made for a more solid film overall. Instead of using The Day After’s method of giving a grand overview of the town where the film takes place, Threads opens with a scene between Jimmy Kemp (Reece Dindsdale) and Ruth Beckett (Karen Meagher), two young lovers parking in a car on a cliff overlooking Sheffield.

The narrative of Threads eventually spins out from the film’s in media res introduction to Jimmy and Ruth to include members of their families. Jimmy tells his obviously working class parents that Ruth is pregnant but that they plan to get married. In an American film, the word “abortion” would never be mentioned, much less implied, but in Threads it is discussed as a viable option for the couple, although one which they do not choose to exercise. It gives the movie the kind of authenticity that contrasts with The Day After’s more parochial, distancing tone. Ruth says (with no irony) that being pregnant isn’t the end of the world, but it’s clear that the escalating tensions that lead to the nuclear attack on the UK---Russia’s invasion of Iran and subsequent US retaliation---are clearly causing her much distress.

Like The Day After, Threads also includes titles but goes one step further, adding voice-overs to help the viewer put what is happening on screen into a larger context with regard to, among other things, a timeline of events. Although this method might seem like it would kick the audience out of the film, at certain points, especially during the bombing and its terrible aftermath, it actually keeps the audience grounded in the bigger picture. The soundtrack of the radio and TV news reports that track the developing situation in the Middle East is often mixed in with diegetic sounds, which creates the impression that not only is everyone hearing the updates at the same time, but also that everyone is trapped in the same situation.

The second important group of characters in Threads is Sheffield’s emergency operations team, led by members of the city council, who set up camp in the basement of the city’s town hall. The film continuously shows public TV broadcasts of how to prepare a bomb shelter and the best way to dispose of bodies. None of these kinds of activities are displayed in The Day After. Granted, the United States had not experienced any foreign attack on its mainland up to this point in time, while London had experienced catastrophic damage during World War II. While this leads the viewer to think that perhaps the people of Sheffield at least would be more prepared than their US brethren, critical analysis of the film reveals otherwise.

A 2003 paper written by University of Nottingham student Paul Binnion indicates that at the time of the filming of Threads there was growing concern that UK citizens were woefully unprepared for an attack of any kind.

“What is frightening is how thorough these preparations are, and how there seems to be no real attempt by government to avert the war. (Duncan Campbell's book War Plan UK [1982] is a chilling examination of these plans. For instance, those civilians with terminal radiation sickness are designated 'zombies', and it is made clear that the authorities would leave them to die, with no attempt being made to help or alleviate their suffering.)”

Socialist newspaper The Morning Star said of Campbell’s book in 2013:

“Campbell exposed the shambolic and amateurish nature of Britain's civil defence at a time when the public were still being peddled the old lie about the threat of nuclear attack from the Soviet Union… [the book] was a forensic, detailed exposé of the way the monarchy, Cabinet and senior military establishment would be secured in secret underground bunkers dictating a form of martial law when, it was clear in the official leaked documents, civil order would quickly break down after a nuclear strike.”

It becomes quickly obvious that despite the emergency operations team’s best intentions, this is exactly what will happen in Threads. They are revealed to be completely useless; in fact, none of the team’s members end up surviving. Not that anyone could envy their deaths. As Threads shows frequently and with frightening detail, death seems to be a blessing. Whatever restrictions US network Standards and Practices imposed on the production of The Day After are nowhere to be found in Threads. Despite the film’s meager budget, the practical effects are almost too believable. The scenes of the bombs are on par with the film’s American predecessor, but it’s the human impact that is more graphically depicted.

The scene of the woman urinating as she gazes upon a mushroom cloud in the distance is just as scary as I remember it. There are other subtle bits that disturb, like Ruth’s mother clutching her shattered eyeglasses in the darkness. Ruth’s elderly grandmother is ashamed of voiding her bowels in her makeshift bed; later they carry her corpse into another room and cover it with a blanket.

More distressing, if not outright horrifying, are scenes of people on fire; charred faces and limbs under the debris of destroyed buildings; uncontrollable vomiting; people screaming from pain; legs being sawed off; dogs and cats dying in the fiery rubble; and rats scrambling over and around blackened corpses. It’s hard to think of a contemporary fictional equivalent to the atrocities on display in Threads, unless we consider the TV series The Walking Dead.

Binnon’s comment about “zombies” is not far from the mark. The physically and emotionally desecrated people who “survive” the blast are quite literally shell-shocked. As one voiceover notes: “In these early stages, the symptoms of radiation sickness and the symptoms of panic are identical.” Ruth escapes the confines of her crumbling house only to witness a litany of human suffering, incomprehensible destruction, and an unceasing rain of fallout particles. Unlike The Day After no one in the film receives a poignant send-off; people simply disappear or die unceremoniously, their desiccated corpses resembling the denizens of the mass graves at Auschwitz.

As such, Ruth becomes one of our guides to the horrors of this post-war world. The others are the intermittent voiceovers and text on the screen that show the numbers: how many millions dead, how many millions of tons of ash have fallen, the secondary diseases that will kill off the population. There is no sunshine in Threads; there is only the bleak grey of a never-ending nuclear winter. In this way, the film resembles more recent post-apocalyptic films like The Road.

Ruth, alone and starving, eventually gives birth in an abandoned barn, alone. A German Shepherd tied to a chain is nearby and lunges at her, barking, as the baby is born. The scene in which she goes into labor and looks for shelter is harrowing, with one shot resembling the cursed videotape from Ringu.

Ruth’s baby, Jane, survives and grows up in this new world, fighting for scraps with other children, none of whom speak coherent English, thanks to the complete breakdown of any sort of educational system. After having sex with another young man, Jane herself becomes pregnant and eventually tries to find a place to give birth. The baby is stillborn and when the nurse at the makeshift hospital hands it to her, she screams silently as the frame freezes and the film ends, almost like Geena Davis’s nightmare in The Fly. It’s one of the bleakest endings in cinematic history, and proves that Threads deserves a place in the horror canon.

While The Day After seems to have lost much of its power to shock in the ensuing years, it definitely made an impact at the time, being recently referenced in an episode of The Americans. Some scenes still resonate strongly, even if the film as a whole does not. For me the horrors of Threads go much deeper, however. I don’t think I’m alone, as others have noted, with some suggesting the film created a new kind of “bogeyman” for young people to fear. Many of us thought that specific kind of fear would end after the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989. Yet we only have to look at photos of Kabul, Aleppo, or Mosul to be reminded that for some, that kind of fear is all they’ve ever known.

You can watch both The Day After and Threads online.