The Corporeal Horror of 'Little Nightmares'

Little Nightmares scares us by turning up the dials on all five of our senses before feeding us to the monsters.

Read More

Little Nightmares scares us by turning up the dials on all five of our senses before feeding us to the monsters.

Read More

Repetition builds habits, habits build comfort, and we chose comfort as our baseline reality. Variation reveals that that comfort is an illusion. Chaos rules.

Read More

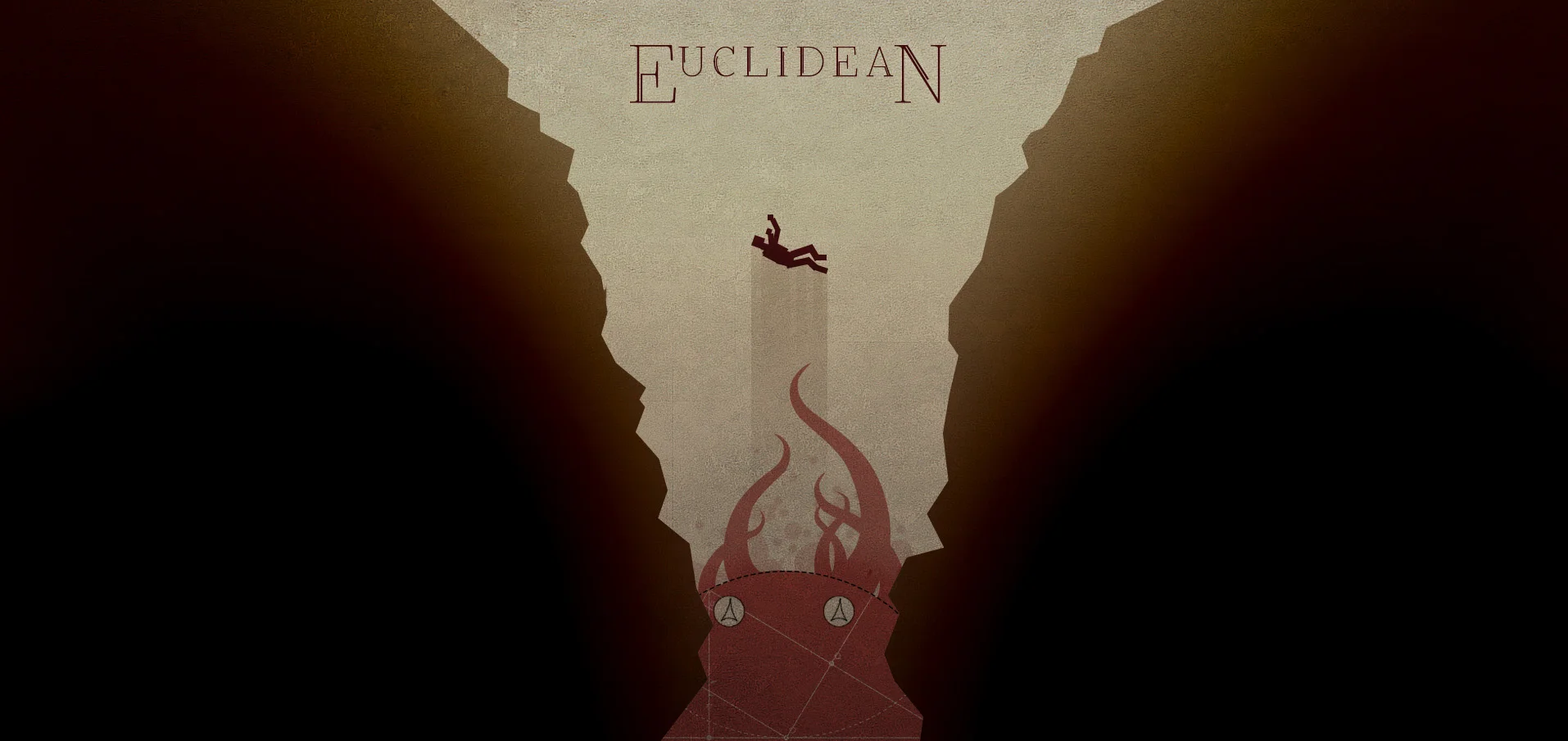

(image via Alpha Wave Entertainment)

There is an inevitability of death that gives your pessimism strength. If you’re the kind of person, like me, who doesn't believe in an afterlife or inherent human significance, then the topography of time begins to feel less like a path and more like a pit. There’s a whole way of living your life where all you do is fall.

Euclidean, an atmospheric horror game best experienced through the Oculus Rift VR headset, embodies the cosmic futility of the falling lifestyle. Mostly it achieves this through its central gameplay conceit: in Euclidean progress is made as you fall through abstract Lovecrafian dreamscapes. You can see your feet dangling below you as you plummet and sink, slowly maneuvering to avoid the geometric demons that threaten to obliterate you on contact.

The game's narrative also unfolds vertically. You begin atop a mountain. A telescope is nearby, it is nighttime and you have just finished painting a neighbouring peak, overtop of which hangs a full moon. If you stare into the face of the bright orbiting rock, it appears to get closer until reality dissolves around you and you begin to move downward.

As you dodge the objects in your path, a disembodied voice taunts you. Its language is prohibitive and antagonistic. It tells you that you ought not to have come to this strange place and asks you the sort of questions that would drive a Miskatonic scholar straight to the asylum.

As you fall through various strata of abyss, it becomes apparent that the end of the game will not be one that you can return from whole. Euclidean is a game of annihilation. You dodge threats and persevere through significantly difficult scenarios only to find death in the end. There is nothing beyond what lies at the bottom of your journey.

Euclidean’s greatest achievement is its ending. Bathed in white light, you are made to feel rewarded for your masterful navigation of the demi-void, presented with the images traditionally associated with heaven and spiritual enlightenment (think the ending of Journey). But of course, there are no happy endings in a universe not made for us. No, all of your semi-purposeful descent was into the gaping maw of something you can’t understand, and which might not even be hungry, but nonetheless, will accept you in its tentacular embrace.

The fall always leads to an end, not unlike the sort that might find you on your way down—the endings we call failure. But like Sisyphus, we take the journey anyway. We sink through the fog and pulsing blackness, filled with questions and fear, because when we’re alive and falling, we might as well take in all the wonderful horrifying atmosphere

Horror isn’t the first word you would use to describe the Metal Gear Solid series of video games – a long running, super popular stealth action series created and directed by Hideo Kojima. Convoluted, sci-fi, self-aware, political and pacifist are better adjectives for the game franchise about the consequences of ideology and war-based economies. Smart but campy, Metal Gear Solid often finds mileage in the supernatural, but rarely trades on fear. And that’s why the 43rd mission in the latest entry, The Phantom Pain, is so remarkable: it scared me to the core.

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain puts you in the role of Big Boss, a war hero turned global terrorist threat, during the the period in his life when his moral alignment ostensibly shifted. The game begins with Big Boss waking from a nine year coma caused by a helicopter explosion, and then proceeding to build a nation of soldiers to help perpetuate a war economy for ideological reasons. The whole thing is really convoluted, so for the sake of examining the horror in mission 43, all you need to know are the following points:

Big Boss has a piece of shrapnel lodged in his skull, making him look demonic and also messing with his memory.

Big Boss is well respected among his nation, lauded as the very embodiment of their ideology which they see as noble.

A major aspect of the game is capturing enemy soldiers you encounter and recruiting them to join your military nation. They provide you with in-game bonuses and when you return to your base, the characters you have recruited are around and interact with you. They have names and hobbies and hopes and dreams.

A key aspect of Metal Gear Solid V’s story revolves around a lethal vocal chord parasite that has become weaponized in a genocidal plot to eliminate certain languages from the planet. It is invisible, it is lethal and it has some kind of rudimentary intelligence. The parasite can learn a language and then go on to exclusively inhabit and kill its speakers.

When episode 43, titled “Shining Lights, Even in Death” is unlocked, near the very end of the game, you are called back to your home base. The vocal chord parasite has evolved immunity to the vaccine you previously developed to prevent its infection and there's been an outbreak on your isolated quarantine platform. You, in a gesture of leadership, enter the sealed off area alone in order to investigate.

The level itself is framed as horror. Screaming people, bloody trails, the occasional begging for help. Emergency lights illuminate the halls in an eerie fashion as you look for a person that might hold the key to identifying the infected. When you finally reach the soldier in question, it’s already apparent what lays ahead of you. He dies and you obtain specially engineered goggles that can detect the parasite in people’s throats. Then the screaming starts.

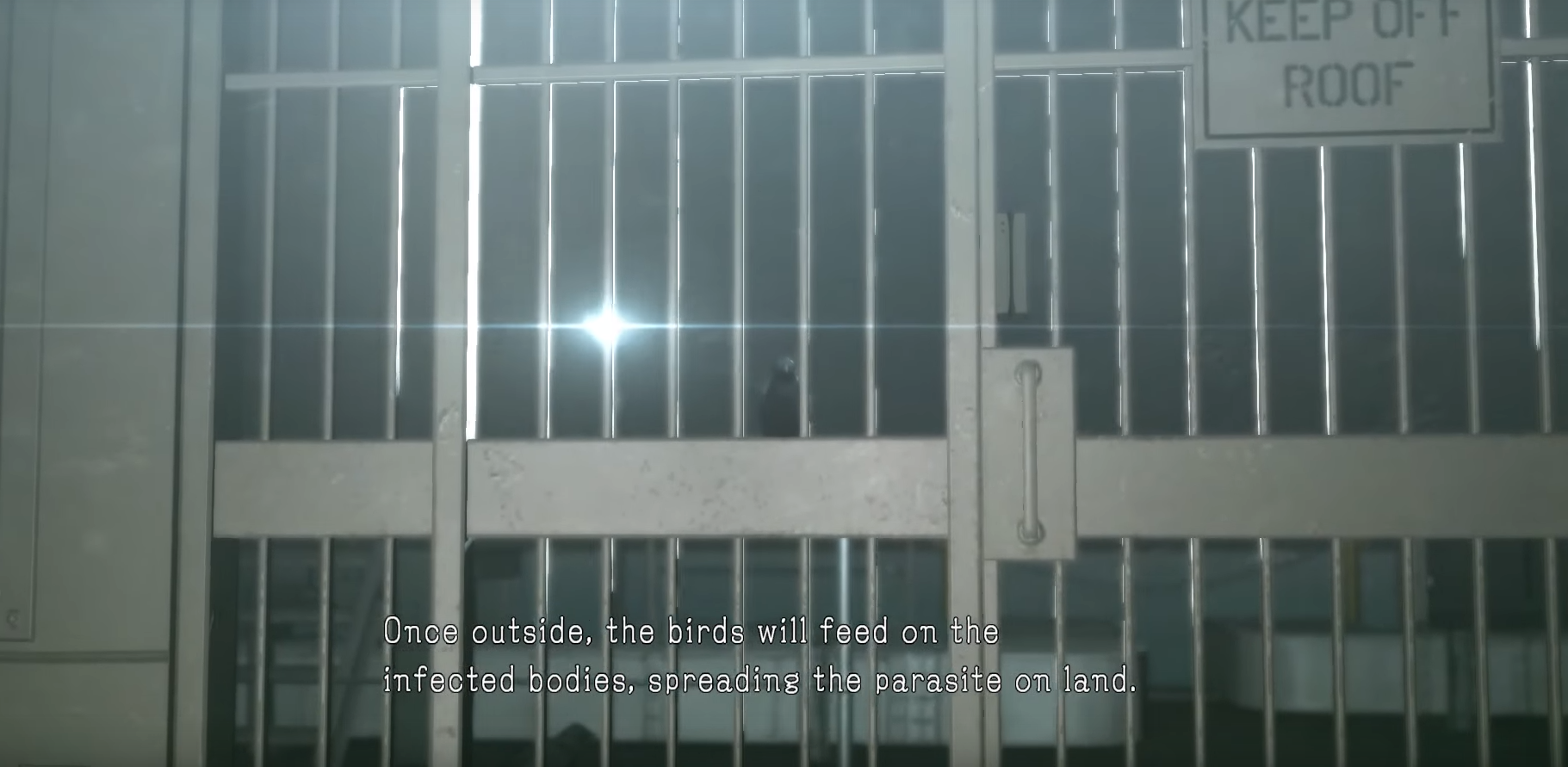

The epidemic horror is ratcheted up immediately after you gain the ability to detect the parasites. You learn that people infected by the parasite are compelled to seek fresh air in service to the bug’s propagation. The stakes are apocalyptic. A gate door to the open air frames a few birds as potential vectors of the final plague as some of the infirmed begin to spasmodically run toward the only exit thirsting for the gulp of oxygen that will end humanity. The game, for a moment, transforms into a zombie story as you are forced to murder familiar faces as a means to protect the world from a climatological threat.

Simultaneously, a great trick is pulled on you, the player. Each person on your base, including those in your quarantine, contributes to the in-game economy. As such, it is important for the player to know when one is taken out of commission. To facilitate this, the game announces staff related events (getting sick, getting injured, getting into fights, dying) with tiny text notifications on the screen accompanied by the stat modifier describing how their departure affects your war business. Therefore, as I shot each zombified member of my hand picked team, I received this message:

Staff Died [Heroism -60]

Once the most zombie-like individuals of my team were dispatched, I descended back down into the dark facility, wearing the new goggles so that I could see who was infected. Sure enough, every human I encountered on the way up, I was forced to shoot dead on the way down. Every person a friend, every friend a bullet, every bullet a statistic.

As this happens the game’s immoral scientist character is screaming at you over wireless. He’s says that you are killing your family, storifying your plummeting heroism statistic by contextualizing your actions as not in tune with the legend of Big Boss. You are a traitor to your family and a traitor to yourself.

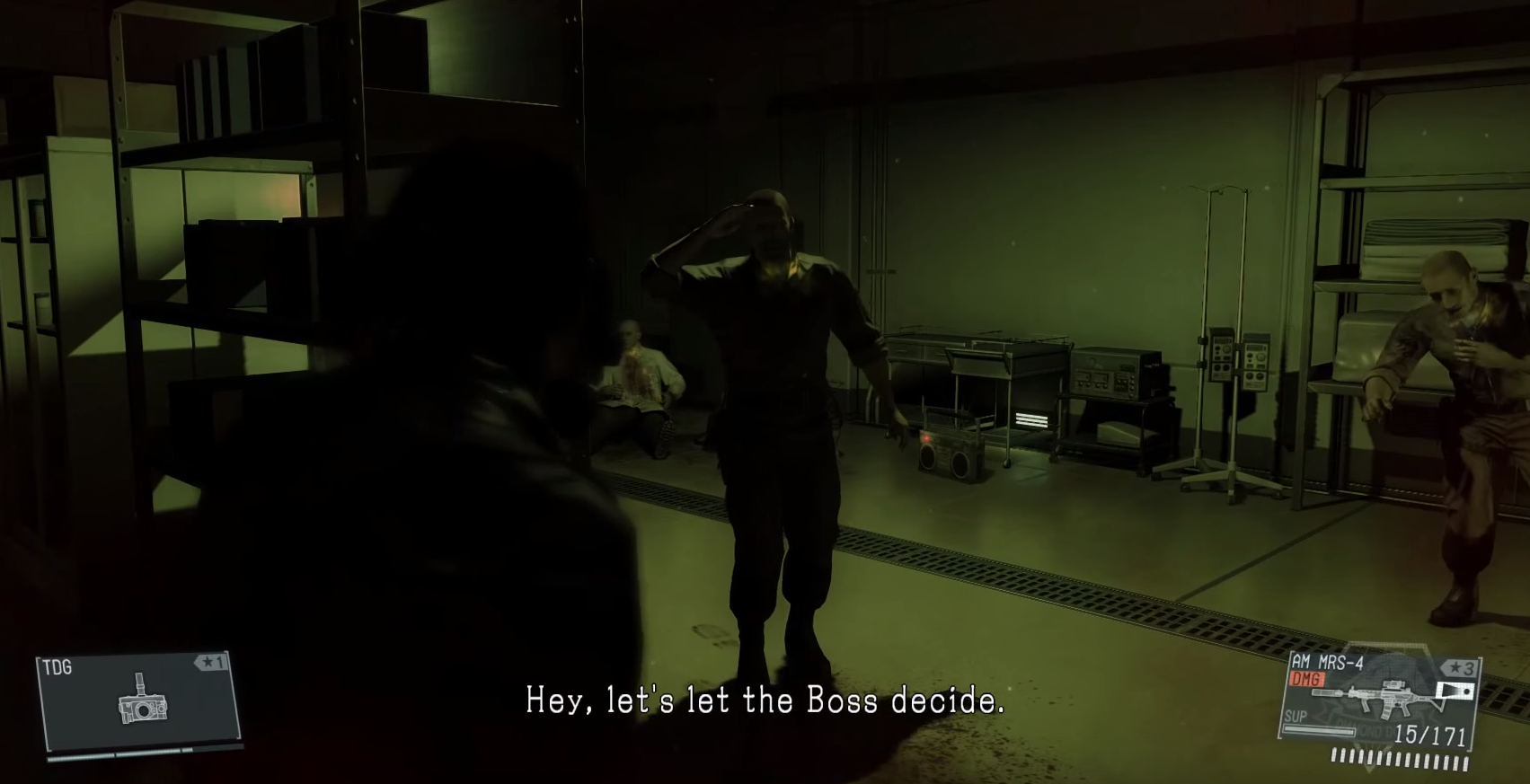

Finally, you enter a room with the last remaining infected members of your personal army. They know what awaits them and they respect you. Big Boss, after all, is a man who represents the ideology that they were already willing to die for. Each man and woman in that room sands and salutes you as the game makes you shoot them all in the head. It is heartbreaking, and I would be lying if I told you my eyes weren't filled with tears as I took control of the avatar of these people’s hope before virtually executing them.

The mission, on face value, is horrific. That’s plain to see. The horror tropes employed effectively portray the stakes of the situation, the climatological threat is the type of invisible unhuman entity we instinctively recoil from, and the rock-and-a-hard place moral decision to kill the infected is the apotheosis of a certain kind of nightmare. All of this is made more painful through the fact that video games are a “lean forward” medium (a term coined by developer Cliff Bleszinsk) – the horrific events in screen can only happen with your participation. No covering your eyes. No hiding under a blanket.

That having been said, the truly masterful stroke of horror in “Shining Lights, Even in Death” is retrospective. After the mission is completed and the deceased are cremated, the final piece of the story can be unlocked. It’s a flashback. You play through the very first level of the game from a different perspective and it is revealed that you are not, in fact, the legendary Big Boss. You’ve just been made to look like him. You have built an army in his name, all the while thinking you were the legend himself, but infact you were just a nameless soldier.

Upon the reveal, I was presented with a terrible balance of emotions. At once I was thrilled – not only was the twist meaningful on a series-wide scale, but I had long suspected this character was not Big Boss so I felt like a smarty pants – and I was also ill. There was a knot in my stomach as I listened to the real Big Boss describe the true events of the game. I was transported in my mind to that dark, blood spattered room, with men and women just like me saluting their hero, who wasn’t even there, as a stranger took their lives away.