Nothing to Fear but Fear Itself: Nevermind

I should preface my opinions of Nevermind, the debut game from Flying Mollusk Studio, with a disclaimer that I have huge respect for passion and innovation. I will always reward trying something new, putting in visible effort, and - perhaps most importantly - not pandering to your audience. So with that in mind, let me start off by saying that designer and team lead Erin Reynold's MFA thesis-turned indie game is definitely a project with a lot of love and effort put into it. It is also, unfortunately, quite flawed. Part of that is due in no small part to what we typically expect from a "horror game," because although it definitely plays into a number of tropes, Nevermind is not a typical horror game.

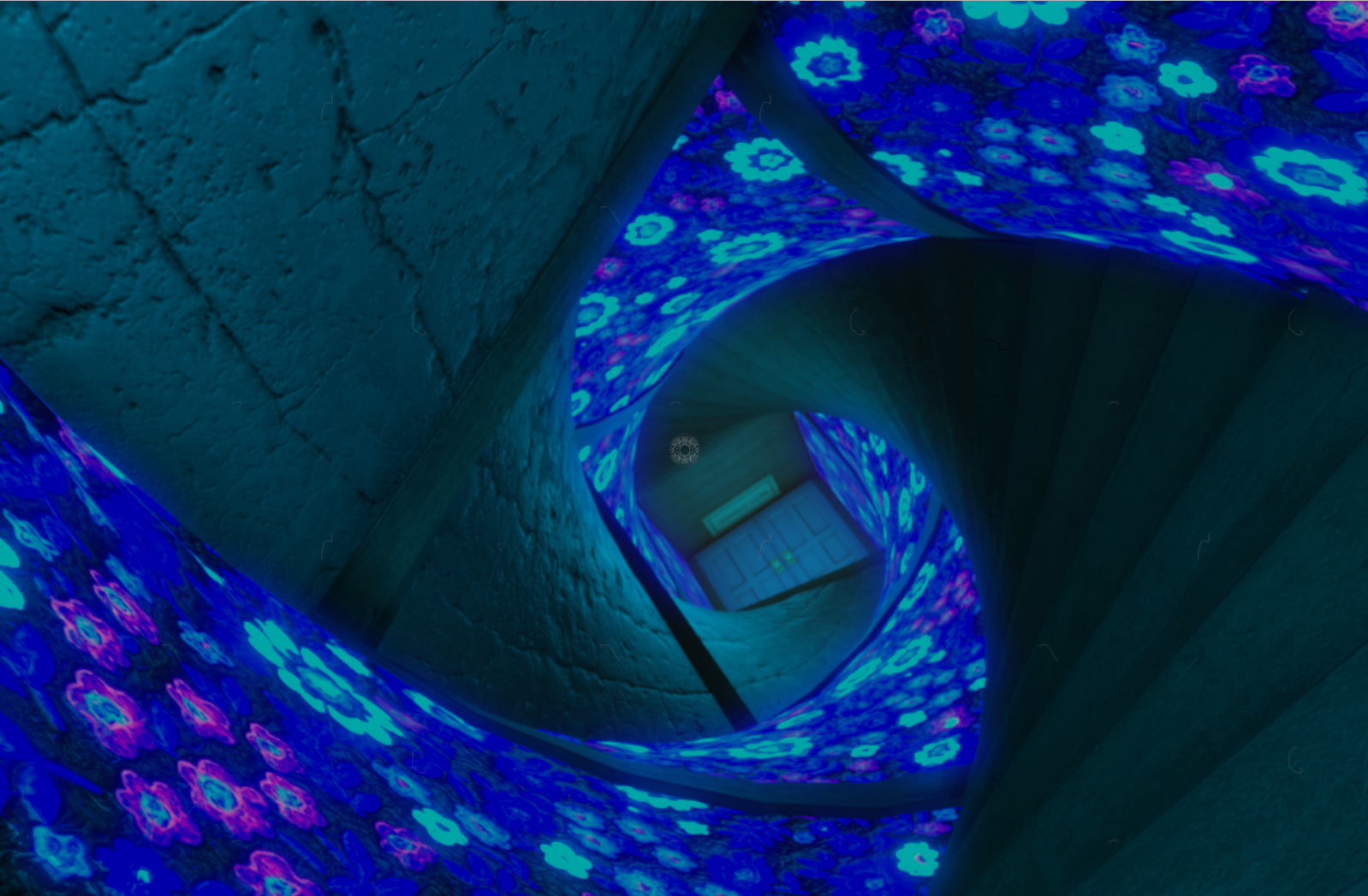

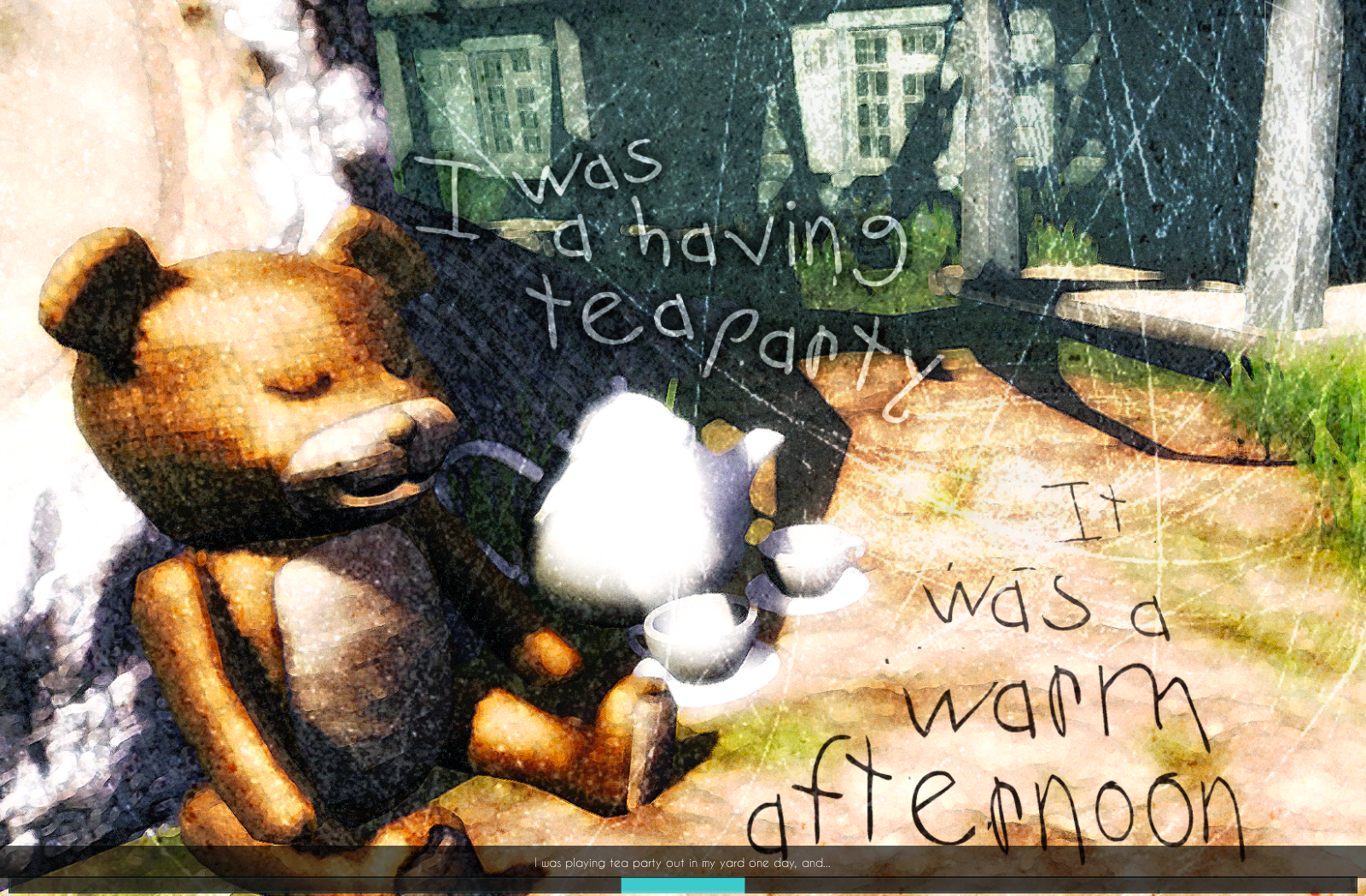

The basic idea behind Nevermind is that you are a therapist at an advanced psychological clinic, the Neurostalgia (yes, really) institute. Through advanced mind-mapping technology, you treat your patients by transplanting your consciousness into their dreams to help them find the root cause of their trauma. It's a lot like The Cell, really, right down to the trippy imagery and spontaneous moments of intense violence. But the innovative idea behind Nevermind comes in two layers. Firstly, the game is billed as one of the very first "biofeedback games." Employing your device's camera, an optional heartrate sensor, and future Oculus Rift support, Nevermind tracks your reactions to the dreamscapes you confront, and, the worse you allow your fear to overcome you, the crazier things get and the harder the game becomes.

It's a terrific, original idea, and the really interesting aspect to it is that the creators have talked, on their site, about how Nevermind could actually be a therapy tool to allow people to conquer their fears. A lot of the game's bonus content echoes this sentiment. There are a handful of "free play" areas that you can access as you complete each patient's level, with soothing music, quiet environments, and little speech bubbles that pop up encouraging you to take slow breaths, calm down, etc. There's also a neat "team memorial" area, common to these types of indie games, but with a cool twist: each person who worked on the game is presented as a statue with their worst fear (spiders, clowns, crowds, etc.).

But here is where Nevermind runs into trouble. I should be clear straight from the get-go that I didn't have a heart-rate sensor, and was playing only with my computer's built-in camera as a metric for checking in on my mental well-being. This might have worked fine if I wasn't a bitter, jaded little man who plays horror games on a regular basis, but as it was, I never once saw the effects of "high stress" that were touted in the game's trailer. There was never a moment, not once, where I felt even mildly threatened, let alone outright scared, and for a game that primarily sells itself on the notion that you have to actively calm down to succeed, that's a problem.

As it is, without this aspect, the gameplay is pretty lacking. You are occasionally presented with a very obtuse puzzle, and, as puzzles go, these are shoehorned in quite awkwardly. In the tutorial stage, the game straight up tells you "sometimes, you're going to run into puzzles." The explanation that this is somehow related to the subject's subconsciousness fighting back is pretty thin, and you can just feel the hand of a designer reaching in to say "We should probably have gameplay in our game." The one consistent thread that is fairly interesting, but still quite confusing, is the idea that you have to map out a patient's subconscious by picking up and re-arranging memories in the form of little postcards you find on the ground. It's interesting because it speaks well to the experience of the character you're trying to help, but it's obnoxious because re-ordering these cards is often a process that makes little to no sense given what you've learned.

Now, I can get that a video game, in some respects, must have some kind of "gameplay," or, well, you'd basically be watching The Cell, like I alluded to before. At the same time, I can't help feeling like Nevermind could have done better to stick to its core mechanic of "fear sensing" and billed itself less as a horror experience. Because as it is, there's some really interesting imagery, some decent voice acting, and definitely a great concept. It's just overshadowed by some really ineffectual attempts at scares and some highly contrived puzzles. For three scenarios that, collectively, work out to about 6-8 hours, the $22 Canadian I paid for Nevermind didn't feel all that well spent, especially with these flaws. And yet...

...I'm just so happy to have played something DIFFERENT. Nevermind is so clearly a game made with an eye to the future, and for a team so fresh out of school, it's a great step. Yes, some of the visuals are a bit hamfisted, and sometimes the writing doesn't always jive (the tutorial level's adaptation of Hansel and Gretel was pretty oddball), but when it does, it sings. They're also committed to putting out more scenarios/patients for the game. If and when they do, I hope they focus on their strengths: inventive, dazzling imagery, strong writing, and an experience aimed less at shocking and startling and more on what it purports to be: therapy. Because that's a really interesting, really worthy idea, and it shouldn't even waste time trying to fit into the normal boundaries of the genre. It's much more exciting to me to see something aimed at redefining what games can do and be for people. So, never mind about what all the other kids are doing, ok? Be your own thing, Nevermind.