Remember to Forget: Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs

Given how much I gushed about Amnesia: The Dark Descent in my post from last week, you can imagine my excitement when I heard that Frictional Games was planning a sequel. For me and other fans of Amnesia's pants-crappingly scary style, the buildup to Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs was huge. Really, if you're a fan of anything and you hear there's a sequel being made, you want one thing and one thing only: the exact same thing as before, only with updated and/or new visuals. Seriously. Think about any franchise announcement you've heard in recent memory. Mad Max: Fury Road. Jurassic World. What made you excited about these things? Was it...the chance for Max to get in touch with his emotions and start a family in a nice, never-moving community? Was it...the chance to finally see Alan Grant teaching at a university? NO. We wanted to see cars exploding in a never-ending chase scene and dinosaurs noshing on people, preferably after some ill-advised "science meddling."

So when they started putting out screenshots and trailers for Amnesia AMFP, everything looked great. They still had the first person perspective. They still had the ubiquitous lantern. They still had the same terrifying sound design, the same shocks and gasps from the player character. And they'd clearly taken it up a notch in the graphics department. Early screenshots showed some very detailed, high-definition environments, in a new and exciting setting. The marketing for this was almost too clever for its own good. Early on, it became apparent to Frictional that they just didn't have the development time to devote to an Amnesia sequel, so they turned to a partner. The reveal for this came in the form of a hyperlink on the Frictional website that took the visitor to a Google Maps location in China. Further Maps hints told us that the new developer would be The Chinese Room.

I'd heard very little about these folks. I knew of them because of Dear Esther, a "game" that I deliberately refer to in air quotes because it is much less a game and much more a strange interactive story. I won't get too much into it because, well, I haven't played it, but my understanding is that Dear Esther consists entirely of an uninhabited world that you wander around while listening to letters. OK.

You can see how I started to get a little concerned.

That said, upon sober reflection that is essentially what you're doing in Amnesia: The Dark Descent. With the added complication that it's mostly pitch black and monsters are trying to eat your face while you slowly mouth out the words on paper. And you know what? That's pretty much what we got with Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs.

And Now, the Game

Like it's predecessor, Amnesia AMFP puts you in the role of - you guessed it - a man with amnesia. Although this time around, the "amnesia" is less a case of memory loss and more a state of delusion and psychosis. Though I'm getting ahead of myself.

You are Oswald Mandus, a wealthy industrialist in London at the dawn of the 20th century. You awaken in your bed from a nightmare in which you saw a huge machine rumbling to life. Your first thoughts immediately turn to the whereabouts of your children, twin boys named Edwin and Enoch. Setting off to find them, you discover your mansion empty, and hear the same rumblings beneath your feet that you heard in your nightmare (which may not have been a nightmare at all).

The story unfolds in a few lateral ways. First, there are the letters and documents you find scattered about, which tell of Mandus' journey to an Aztec temple, his return, and his subsequent construction of a new factory and business. Second, there are a number of phonographs, which contain recordings of an interview between Mandus and "Professor A," a man sent by an organization to determine Mandus' mental well-being. Finally, you are also contacted in real-time by a mysterious stranger via several phone-boxes that are installed throughout Mandus' factory and facilities. This stranger advises you that your missing children are trapped far below in the factory, and will drown in floodwaters that have been released by an unknown saboteur.

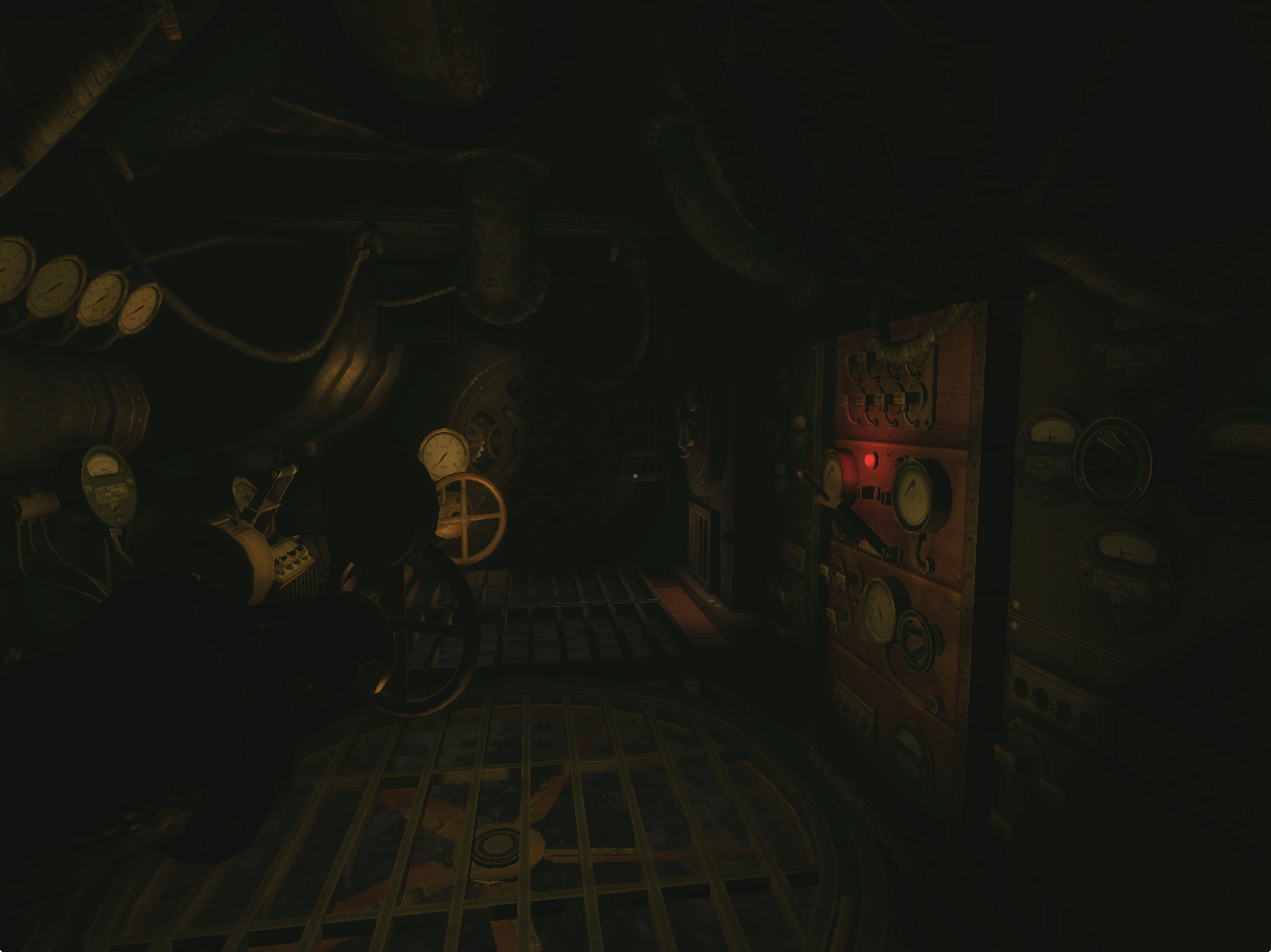

As you may have already guessed, there is much more at work here than meets the eye, and the titular Machine for Pigs' origin and purpose are inextricably tied to Mandus' own mental problems and mysteries. Most of the puzzles of the game come from repairing the damage done by the saboteur to the machine, which involves a lot of pulling switches and spinning wheels to activate a colorful variety of steam-driven technology.

The puzzles (such as they are) are much more simplistic than The Dark Descent because you no longer have an inventory. Indeed, you no longer have a status screen, since A Machine for Pigs also takes away Flints, Oil, and Sanity (Health remains, though it regenerates automatically over time and thus a health bar is not shown or needed). The lantern you receive is electric, and never needs refilling. Light sources in the environment are now permanently lit or are lamps that can be turned on or off with a click.

OK, but is it Scary?

The removal of a lot of the mechanics of The Dark Descent definitely does hurt A Machine for Pigs in the scare department. With TDD, remaining in the dark had some serious penalties. You treasured the light, and at the same time had to strike a balance with it to avoid being killed by the monsters. Here, you can simply plunge yourself into permanent darkness, or, if you're feeling bold, keep your light on all the time knowing that it will never run out.

The environment is absolutely stunning, answering my complaint about TDD's static level design. Here, you have a richly decorated mansion, a creepy church basement, a variety of brass and copper in the factory, and a grimy sewer. There's even a few outdoor segments, which admittedly do have the usual problems of outdoor areas in any 3D game (especially poorly defined boundaries that are usually forced by unrealistic scenery placement such as overturned carts).

And, though the sanity meter's loss is keenly felt, this game still manages to be very, very scary. As with TDD, there's a real sense of dread and despair throughout this game, punctuated by the jolts and bumps of the machine groaning like a sleeping Old One underground. There's also a fantastic musical score in this game that effectively enhances moments of suspense - and also moments of surprising emotion.

Where AMFP excels is in the story department. Every piece of dialogue and written record in this game is a work of poetry, with evocative language that communicates the time period and sentiments of the age wonderfully. It can, at times, be a bit ham-fisted (pun most definitely intended), with so many pig metaphors thrown in that you'll be ruminating on the origins of bacon for weeks after your first play through.

There's also a lot of sexual imagery and religious undertones thrown into the mix, the intent of which seems to be to disturb more than to frighten outright. Indeed, this game, while containing a number of "NOPE NOPE NOPE" moments, strives to leave a lasting impression of unease more than a sense of outright terror.

The final sequence, in particular, is an impressive monologue that brings into question the very nature of human progress. The game's obsession with machinery echoes Mandus', demanding an answer to the cost of the industrial revolution. The recurring theme of children and birth is obviously tied to this; so much of the Victorian British empire - and many others before and since - was created on the backs of child labour.

Mandus teeters on the brink of sanity with the aid of a selective memory, or a selective Amnesia. Perhaps society at large has a selective memory as well. When we think about how far we've come, we feel a sense of pride. But A Machine for Pigs reminds us that we may have forgotten a sense of horror.