The Strange Game: When Sherlock Holmes Meets H.P. Lovecraft

Neil Gaiman’s A Study in Emerald won the Hugo Award in 2004 and for good reason. The premise of the story seems like an exercise in paradoxical thinking: what if Sherlock Holmes existed in the world of H.P. Lovecraft? In the introduction to his 2006 short story anthology Fragile Things, Gaiman summarizes the obvious problem:

“...the world of Sherlock Holmes is so utterly rational, after all, celebrating solutions, while Lovecraft’s fictional creations were deeply, utterly irrational, and mysteries were vital to keep humanity sane.”

The text of A Study in Emerald can be read on Gaiman’s website. It is a variation on A Study in Scarlet by Arthur Conan Doyle and focuses on the murder of a member of the royal family. An Afghanistan war veteran (our narrator) and his almost impossibly astute consulting detective of a flatmate, while pursuing the details in the case, are set into a battle of wits against a set of doppelgangers we eventually learn to be the real Holmes and Watson.

Gaiman’s story takes place in an alternate London in which the Great Old Ones of Lovecraft have conquered humanity and instated themselves in our ruling positions. My favorite passage, which describes Queen Victoria, also serves as an example of the Eldritch tone Gaiman brings to his strange 18th century London:

“She was called Victoria because she had beaten us in battle, seven hundred years before, and she was called Gloriana, because she was glorious, and she was called the Queen because the human mouth was not shaped to say her true name.”

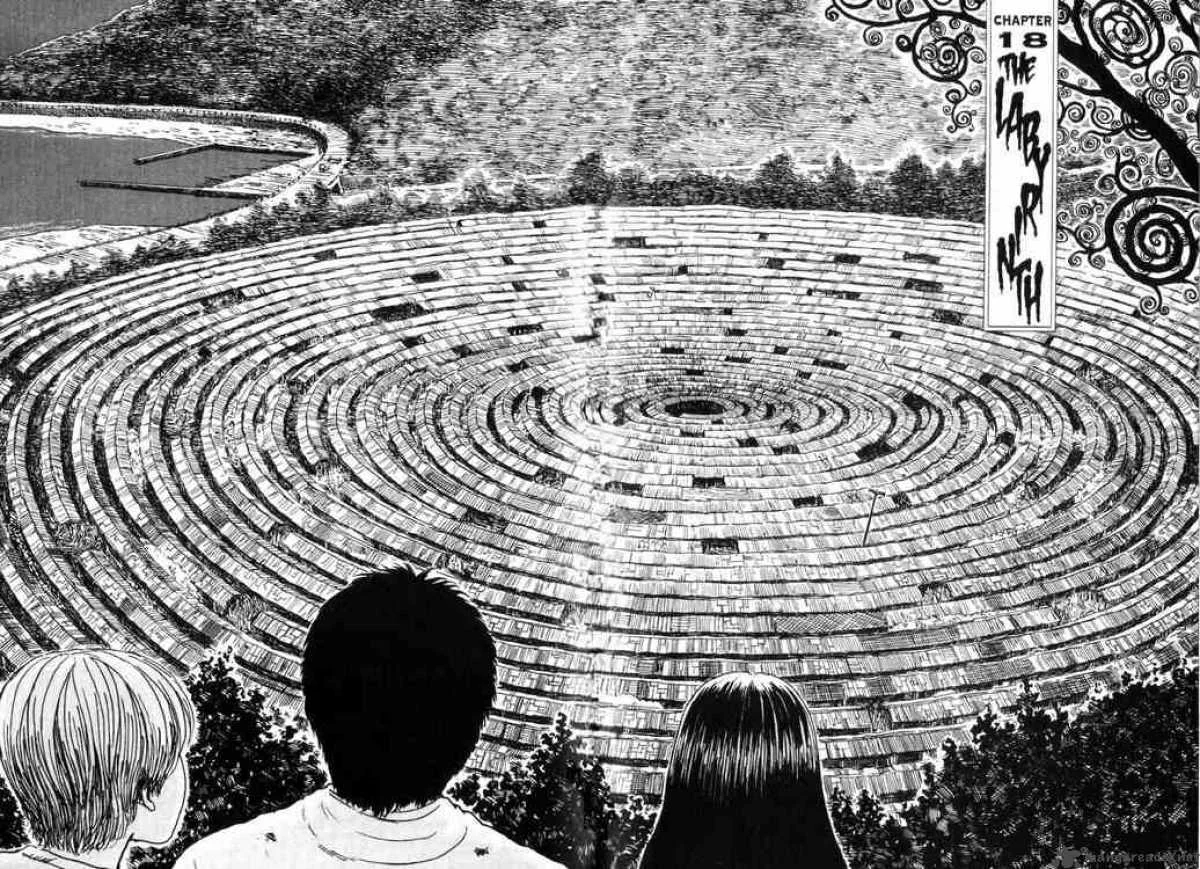

Glimpse into the alternate reality provided by MS Paint.

As the mystery progresses, it becomes clear that a type of humanist morality is being invoked and we are following the story of unwittingly evil detectives. Holmes and Watson, the antagonists of A Study in Emerald are labeled as restorationists, who wish to overthrow the Elder Things that have conquered our species, opting for a world that is truly for us. A note left for the narrator's evil-Sherlock summarizes these thoughts:

“I send you this not not as a catch-me-if-you-can taunt, for we are gone, the estimable doctor and I, and you shall not find us, but to tell you that it was good to feel that, if for only a moment, I had a worthy adversary. Worthier by far than inhuman creatures from beyond the pit.”

The sentiment from one Holmes to another, darker Holmes is affirmative of the human spirit and never fails to fill me with hope. In the face of unceasing oppression - whether it be that of institutional religion, a Lovecraftian allegory for it, or simply the void itself - nothing is a stronger weapon than a reminder of humanity and the good we do to each other.

A Study in Emerald, in creating an opposition between genres, illustrates why detectives are true heroes in the face of horror. The instinct, as Gaiman articulated, is that classic mystery fiction and cosmic horror are diametrically opposed, but it is actually in their blending that we can understand how to live heroically underneath the looming void.

There is a great, long standing tradition of detective stories crossing over with horror. Paranormal investigator fiction is one of the most popular and accessible horror sub genres because it allows for the possibility of understanding through a heroic detective. From William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki The Ghost Finder and his electric pentacle to Mulder and Scully, horror has been made accessible through the tropes of detective fiction for over a century.

It’s true that in many ways having a deductive hero at the center of a horror story subtracts from much of the actual scariness of a narrative, but the lessons we can learn from these stories are deep and affecting. This is particularly true in more recent examples like True Detective where the horror is subtle and the unknown is in many ways unknowable. In this case, the detective’s role is to gaze into the void and when they find no answers, return to the world a better human after having confronted a boundary.

The detective, when placed in the tradition of cosmic horror, is heroic for holding on to humanity in the face of forbidden knowledge that would drive weaker willed individuals mad. They are the explorers and prospectors of existential frontiers, a testament to our unshakable human condition. They, like Gaiman's strange Sherlock, are able to look into the darkness for meaning and upon finding the incomprehensible accepting the challenge of living as a human in the abyss.