Climatological Horror in Nyarlathotep

Cover of Nyarlathotep illustrated by Eisner Award winning Chuck BB. You can actually buy this edition through Boom! Studios. (This is not a paid ad, I just think it's about the coolest thing out there).

Cthulhu gets all the credit, but the first of H.P. Lovecraft’s weird pantheon of other gods was Nyarlathotep, the Crawling Chaos, introduced in a very short story that shares his name. As a work of classic horror fiction, Nyarlathotep is mostly recognized solely for the creation of its titular deity who, in addition to appearing in several other of Lovecraft’s more popular stories, has a prominent place in the expanded Cthulhu Mythos (particularly the RPG and board games). But Nyarlathotep is quite remarkable on its own as a piece of microfiction, if for no other reason than presenting a distilled example of climatological horror.

Horror of the unknown, which is the base of all true horror, further deconstructs to a confrontation with the border between the world that we live in and the one that would exist regardless of our continued survival. It’s a paradoxical thought, because in order to think we also need to exist, but there is a primal, nauseous part of our minds that, while unable to comprehend non-existence, can begin to contemplate it. In fact, we can come close to observing it, by beholding sublime meteorological events like severe storms that are both unthinkably larger than us and completely indifferent to our lives.

It is through this relationship between human and weather that we are introduced to Nyarlathotep:

“There was a daemonic alteration in the sequence of the seasons - the autumn heat lingered fearsomely, and everyone felt that the world and perhaps the universe had passed from the control of known gods or forces to that of gods or forces that were unknown.

“And it was then that Nyarlathotep came out of Egypt.”

Aside from being a delicious example of Lovecraftian prose at its most heavy metal, the above passage is more than an overwritten bit of pathetic fallacy. In your average ghost story, this literary device is imposed by the author to guide a reader to certain conclusions about what she should be feeling - darkness is shorthand for mystery and anticipation, storms foreshadow drama, a sunny day means safety. In Nyarlathotep this is not the case; the weather is more than just style and shorthand.

In Nyarlathotep there is a connection between the weather and the elder one’s arrival. Rather than a signal for you to be uncomfortable, the god-killingly hot autumn that the narrator of the story experiences is essential information to the horrific narrative. Nyarlathotep has arrived on Earth - a non-human in the world for humans - and our planet has become less for us as a result.

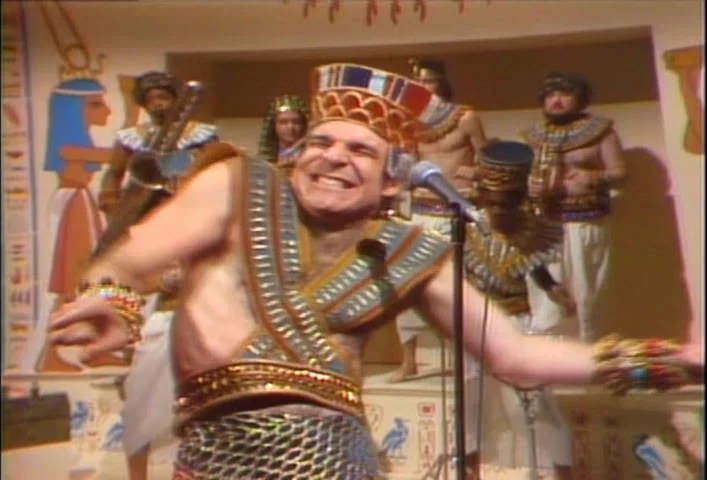

The Crawling Chaos takes the form of a lithe man, dressed as a Pharaoh, who travels the world and performs Tesla-esque public marvels. It’s through viewing one of these magical performances, which are described as projections of apocalyptic visions, that the narrator attempts to reject Nyarlathotep’s divinity:

“And when I, who was colder and more scientific than the rest, mumbled a trembling protest about “imposture” and “static electricity,” Nyarlathotep drave us all out, down the dizzy stairs into the damp, hot, deserted midnight streets.”

The narrator sees a glimpse of the paradoxical world without him and rejects it in a manner most befitting a white man of the early 1900’s: by forcing it to fit his paradigm. Later, he and friends drink and mock the horrors they saw, but the weather is still changing regardless of their beliefs. People can no longer sleep through the wee hours of night, opting to fill it with screams instead. Also the moon is green.

It’s while finding his way home under that strange moon that the narrator finds himself brought forward into Nyarlathotep's apocalyptic vision and made to behold the world without us.

“...I half-floated between the titanic snowdrifts, quivering and afraid, into the sightless vortex of the unimaginable.

“Screamingly sentient, dumbly delirious, only the gods that were can tell. A sickened, sensitive shadow writhing in hands that are not hands, and whirled blindly past ghastly midnights of rotting creation, corpses of dead worlds with sores that were cities, charnel winds that brush the pallid stars and make them flicker low.”

At play here we have the language of weather mixed with Lovecraft’s oft-parodied un-speak (hands that are not hands, climbing a ladder but falling in the diagonal, etc). The hot autumn that accompanied Nyarlathotep has grown to consume the planet and now everything is cold. What follows is the most horrific of all Lovecraft’s cosmic pictures, the graveyard of the universe that we will one day fertilize, in which things still happen despite our absence.

It feels embarrassing to admit, especially in the face of our own very real (but still poetically Lovecraftian) climate change, but the natural human reaction is to assume that once we’re all dead everything will just come to a stop. The knee jerk reaction is that hurricanes, heatwaves, tornadoes and inter-dimensional invasions can only happen to us, the audience. But that is not the case, and that fact is the wonderful, horrific majesty of Nyarlathotep.