Madness, Enlightenment and The Festival

Marblehead, Massachusetts (via marblehead.org)

What can H.P. Lovecraft's The Festival teach us about madness in horror?

Read More

Marblehead, Massachusetts (via marblehead.org)

What can H.P. Lovecraft's The Festival teach us about madness in horror?

Read More

The climate is changing and maybe there’s nothing we can do. Our world is not one that requires us, and as we all start to make that realization we turn to cosmic horror in order to better understand our pessimistic, apocalyptic fears. Elder Things, Dreamlands and colours from out of space all offer us a fantasy window into realities that don’t require human eyes, and perhaps are best viewed with other unspeakable senses. When it comes to these horrific viewing glasses few are as clear as Gyo, by Junji Ito.

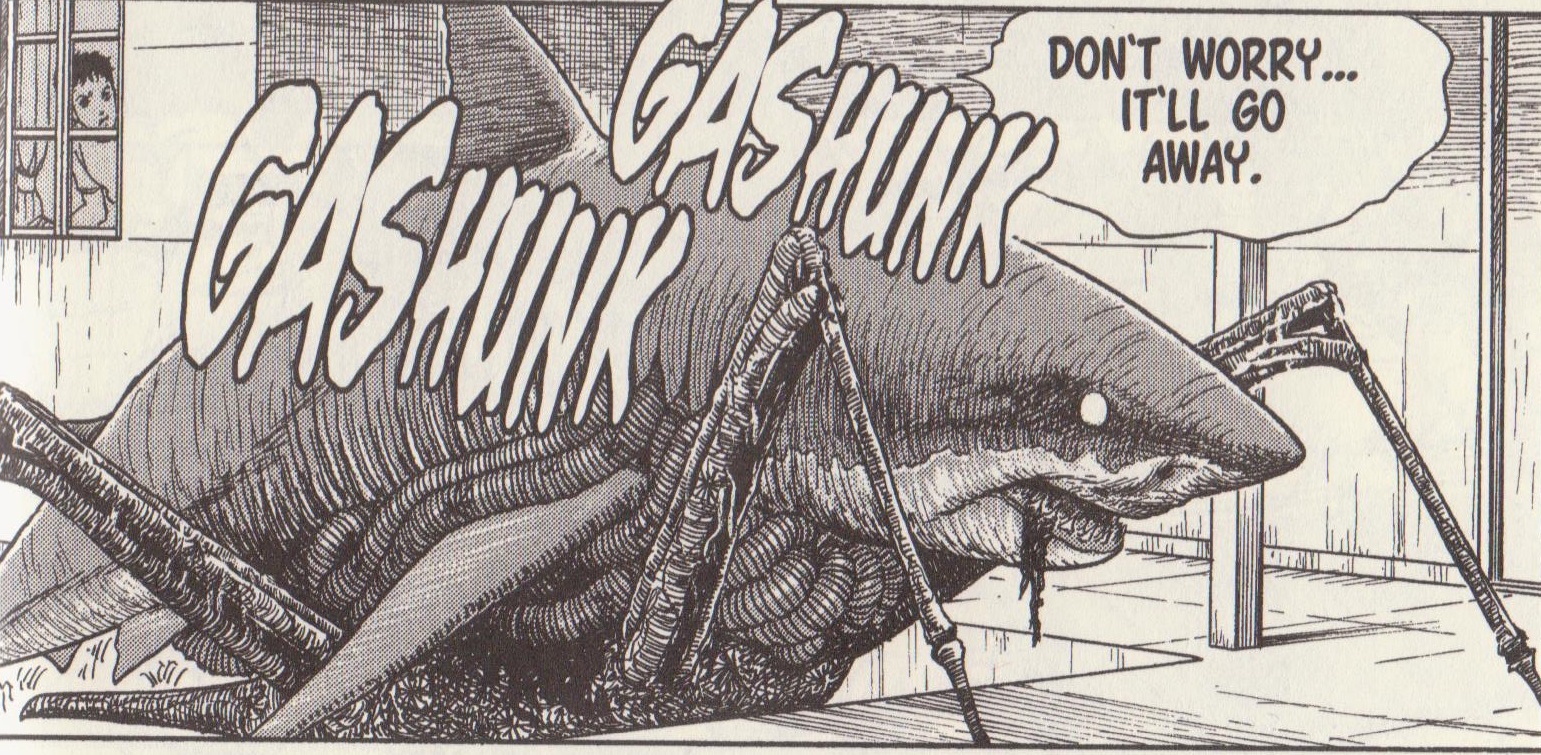

A horror manga about an ancient germ from the depths of the ocean, Gyo works as an allegory for climate change. Part pandemic thriller, part creature feature, the story begins with the invasion of Okinawa from the sea. Marine life with sharp, spindly legs begin to crawl onto land and terrorize the human population. The invasion spreads to the rest of Japan and eventually the world, before moving to the next, much more horrific stage.

From the very first chapter, Gyo evokes the creeping feeling of cataclysmic global change by characterizing its monster as an invisible invader. The fish with legs are heralded by a terrible stench, described by characters as being reminiscent of hot human corpses. To the reader, such characteristic makes you double blind. Not only can the menacing germ not be seen, you can’t smell something in a story. You are left knowing that the helpless characters are overwhelmed by a paranormal odour because they are constantly screaming about it, and while you’d think that to be a mercy, there’s something very upsetting in being told about a sign of danger that you can’t notice yourself.

I held my breath while reading Gyo because of the fictional smell. It was a subconscious reaction to the horror on the page, and it amplified my gasps when the book actually left my mouth agape in shock. There are images in Gyo that—while not as deeply nightmarish and intellectually disturbing as some of what’s contained in Ito’s more famous Uzumaki or his one-off the Enigma of Amigara Fault (which is contained at the end of the delux edition of Gyo from Viz Media and actually keeps me awake at night)—actually left me in disbelief.

The whole effect is a suffocating feeling as you progress deeper and deeper into an adventure that simply can’t have a happy ending for humans. Gyo is the tale of a world turning its back on humanity, taunting us with the stench of our own decomposing bodies as if to say Nothing lasts forever, but you are much more fleeting than I.

What really hammers the whole thing home, and therefore makes Gyo essential reading for the modern horror fan, is the sense of guilt Ito pours into his characters. The humans blame each other for the monstrosities, the stench and inevitably their own failure to save themselves and eachother. Yet, not a single person within its pages did anything wrong. As the need to point fingers recedes, Gyo settles into a passive, contemplative mode only achievable in moments of deepest pessimism. What if no one’s to blame? What if we are so insignificant that we didn’t even cause our own tragic demise? When it’s all over, and we are wiped out by an indifferent entity with nothing we would call memory, did we even exist in the first place?

Gyo is available anywhere you can buy manga. Go get it.

(image via Work in Progress)

“That night we talked about the tower, although the other three insisted on calling it a tunnel.”

When we reach the limits of language, we find ourselves on the border of madness and contradiction. It is the place of the Lovecraftian gods, where up is diagonal, down is light pink and forward is twirling. The concept of this absurd state of thought is rich in horror, and it is often invoked in the genre - especially in the weird fiction subgenre - to evoke that elusive paradoxical thought we call the void. The trope very rarely is used to great effect (I particularly find it campy and fun to parody) but when it works, like in Jeff VanderMeer’s novel Annihilation, it really makes it tough to sleep at night.

Annihilation is the first entry in Jeff VanderMeer’s 2014 weird fiction masterpiece The Southern Reach Trilogy. The best fiction I read last year (I included it on my Best Of 2014 list for Popshifter), The Southern Reach manages to tell a beautiful story about humans encountering the world-without-us - a place at once familiar and impossible to comprehend because it is a thing we cannot behold by virtue of its definition. It’s the goal of cosmic horror, to conjure this paradoxical thought, and VanderMeer does it with style and sublime aesthetic that manages to feel addictive and terrifying all at once.

The key to achieving this negation of humanity for the reader lies in a prominent symbol introduced at the top of Annihilation: the tower. The book is told from the perspective of an anonymous biologist, one member of a four woman team sent on an expedition into the mysterious Area X. The story begins when they encounter a structure within Area X that does not appear on their map of the strange wilderness. This is the tower, but it is also not a tower.

(image via Work in Progress)

Described in the book initially as a circular slab made of coquina and stone with a rectangular opening onto descending stairs, the biologist’s companions all rationally call it a tunnel. That said, the biologist labels it as a tower before even that most basic description, illustrating something tall rather than deep. The word, which effectively describes the exact opposite of what it’s labeling, is used for the duration of the first volume so that as a reader when you see “tower” you picture a tunnel.

What’s more is that through our implicit trust of the narrating biologist, who is incredibly sympathetic despite her cold demeanour and air of mystery, we understand that her dissonant naming is involuntarily affected - a result of being in Area X. She almost immediately admits, through the description of her nomenclature logic, that her insistence on the word “tower” is insane:

“At first I only saw it as a tower. I don’t know why the word tower came to me, given that it tunneled into the ground. I could easily have considered it a bunker or a submerged building. Yet as soon as I saw the staircase, I remembered the lighthouse on the coast and had a sudden vision of the last expedition drifting off, one by one, and sometime thereafter the ground shifting in a uniform and preplanned way to leave the lighthouse standing where it had always been but leaving this underground part of it inland. I saw this in vast and intricate detail as we all stood there, and, looking back I mark it as the first irrational thought I had once we had reached our destination.” p.7

By describing a tunnel as a tower, VanderMeer manages to familiarize readers with negation. By virtue of being wholly visible, a tower has perceivable limits. A tunnel does not have this. Only the parts that have been experienced can be said to even exist, and beyond that anything else is implied or expected based on hope or human estimate. Additionally, by invoking the negative label, the author has avoided the awkward unspeak pitfall of having to write out things like “I fell up and to the right, sliding down, (or was it out?)” Since tower implied height instead of depth, the mind-bending is taken care of in passages like this:

“With the tower, we knew none of these things. We could not intuit its full outline. We had no sense of its purpose. And now that we had begun to descend into it, the tower still failed to reveal any hint of these things. The psychologist might recite the measurements of the “top” of the tower, but those numbers meant nothing, had no wider context. Without context, clinging to those numbers was a form of madness.” -p22

Annihilation and its subsequent volumes (Authority and Acceptance) go on to require the reader to continue thinking difficult, contradicting thoughts, and it is because of the tower that it all works out to such great effect. The Southern Reach Trilogy can be called a magnificent achievement in horror simply for its depiction of that impossible place with a builder that cannot be imagined, a place that cannot exist yet feels so real.