The New Necronomicon

Get it? All Has Read?

There once was a little boy, who having been given access to his grandfather’s library and read the entirety of Grimm’s Fairy Tales and Arabian Nights, had his mother refurbish his room to reflect his new obsession. Outfitted with curiosities and trinkets from far and wide, the boy abandoned his name so that he might adopt another, one perhaps more suited to his tastes for all things readable. And so was born Abdul Alhazred, who would go on to pen the one text no human would ever read (because it would never truly exist): the Necronomicon.

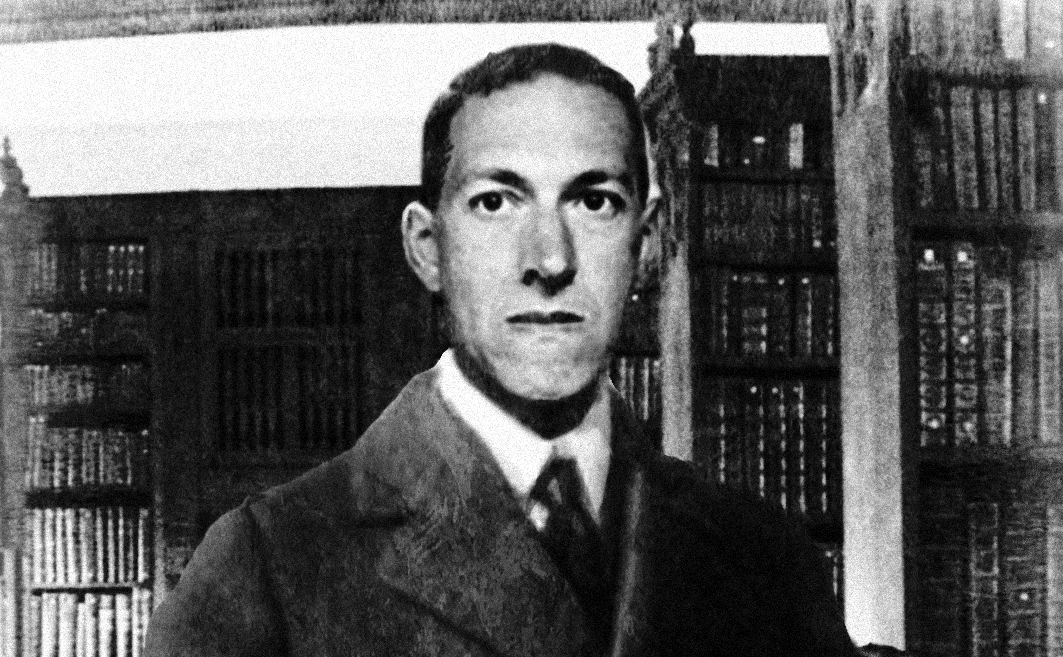

According to Paul Rolland’s essential biography, The Curious Case of H.P. Lovecraft, that is how the man most credited with inventing modern horror came up with one of his most influential characters. Abdul Alhazred wrote arguably the most infamous imaginary book of the past hundred years, a book that contains the most forbidden knowledge ever to occupy human grey matter and that can unleash unknowable cosmic horror upon our world, showing us our true universal insignificance. The Necronomicon: a book whose name alone evokes the darkest of all thoughts; things written that should not be read.

Perhaps you can see where this is going. In preparation for this blog post I have been reading the letters and prose of H.P. Lovecraft, and whenever I do that I tend to adopt his telltale love of unapologetically purple writing, so I may have been a little heavy with the above allegory. It was only half-accidental. Lovecraft is, after all, nothing if not influential. Of course, that’s not all he was. H.P. Lovecraft was also a bad person, a white supremacist who has dodged posthumous judgement for nearly a century on behalf of forgiving or naive fans. It is, after all, a rare occasion that the already appropriative caricature of Alhazred is mentioned without his infamous and racist title “the Mad Arab.”

Time has caught up with the father of Cthulhu though, and as the culture shifts to better represent those who have been oppressed by Lovecraft and people like him, it can no longer be avoided. H.P. Lovecraft was not a good man, and his prejudice permeates his writing, both fiction and correspondence. To many horror fans, including myself, this is distressing.

How do you read such an unpleasant thing?

Indeed, the reevaluation of Lovecraft has resulted in the removal of his personal iconography. The World Fantasy Awards, up until and including this most recent year, used to give winners a trophy molded in the image of H.P.’s head, but a petition has lead to the decision to change the award statue to resemble that of African-American sci-fi author Octavia Butler. The decision is progressive and right headed. Genre is the tool of subversion, and to have an award for excellence in the literary area literally be the face of oppression strikes me as ironic in the worst way.

But as the evaluation of Lovecraft has rightly drawn the man’s character into the harsh light of scrutiny, so has the status of his life’s work which is peppered with flecks of the author’s toxic worldview. It’s an uncomfortable thing for an enthusiastic Lovecraft reader to confront (speaking as one myself), especially in this age of fandom that seems to increasingly demand a complete and unconditional love of one’s professed cultural interest.

(As a side note to illustrate this modern paradigm of fandom: when the Everything is Scary list of essential X-Files episodes was shared on Reddit by a reader, I was accused of not actually being a fan of the series for having taken a critical perspective on the show. This struck me as terrifyingly ignorant. How can one be said to love a thing if they haven’t also entertained the idea of not liking it? Or even asking themselves why they like it? Or what parts they love most?)

To dismiss Lovecraft’s work outright, as some have done in the wake of the World Fantasy Awards trophy change, ignores the most important aspect of his catalog: it belongs to us. And I don’t mean that in an exclusionary way; I mean it with the passion of a progressive revisionist. The imagery, the concepts, the tentacles, all of the things that have come to symbolize Providence’s most controversial export, those are the property of horror fans of all races, genders, orientations and, well, probably not creeds—no matter how you slice it, Cthulhu and his pals are at least blasphemy.

We are introduced to Lovecraft in a Mythos-first fashion. The world he’s credited with creating, the “Cthulhu Mythos,” is the Lovecraft brand, but it isn’t even a creation of his own. The term was coined after the author’s death by August Derleth who claimed to posthumously collaborate with H.P., but really just wrote his own stories around the dead man’s unfinished fragments (Lovecraft actually called his connected stories “The Arkham Cycle”). From Derleth and his contemporaries onward, the world of Lovecraft has been fleshed out and developed by countless readers and writers. It’s from this point, far out of Lovecraft’s actual reach, that a curious investigator looks back into time and finds the source, having been seduced by collaborative branding into thinking they like the short stories of a racist grouch.

But what is the effect that reading these forbidden texts has on the reader? Sure, there are some who, unable to keep a critical mind might run screaming to the comfort of the light, scared of the words on the page—things that shan't be quoted, uttered, or adapted for the stage without revision—and warning others not to look. Those who can remain sound of mind, however, will benefit from the same thing that inspired horror’s greatest practitioners who, having not yet died, we assume are as progressive as we want them to be.

Neil Gaiman’s A Study in Emerald, a Sherlock/Lovecraft mashup which won the Hugo Award; Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, an all-woman modern retelling of At The Mountains of Madness except actually scary enough to keep you up at night; most of what Stephen King has written that’s worth reading; practically everything Guillermo del Toro has ever done—these are the flowers that have grown on Lovecraft’s repugnant and desecrated grave. Perhaps most remarkable though, are the games inspired by the Mad New Englander.

In 2015 two videogames progressively subverted Lovecraft’s legacy of hate through appropriation. Sunless Sea is a Lovecraftian roguelike set in an underground ocean, using all the beloved hallmarks of its source material—tentacles, insanity, unknowable gods, exploration and adventure—while giving its player complete freedom to define their character identity right down to the pronoun they prefer (you can even choose to not have a pronoun).

Bloodborne, meanwhile, is a major win for progress, telling the greatest Lovecraftian tale the man was incapable of telling because of his prejudice. Created by Japanese developer Hidetaka Miyazaki, the game perfectly captures the cosmic nihilism, paranoia and even xenophobia of Lovecraft while revising the socially problematic parts to better underline the nihilism at the core of what both artists are trying to communicate.

The greatest accomplishment that the amazing works of horror Lovecraft has inspired is that, through the reimagining of context in an inclusive way, each has actually achieved what the dead man from Rhode Island always attempted in his fiction but to a greater degree of success. In an oft-quoted 1927 letter to Farnsworth Wright, the editor of Weird Tales magazine, Lovecraft sums up his contribution to horror quite succinctly: he wants to create tales that negate the human. In this manner, though, he fails only because of his misgivings. Many Lovecraft apologists try to paint him as an equal opportunity misanthropist, but it’s clearly not true. The author's white supremacy has betrayed his stated intention, because when we are all nothing we are also all equal. Lovecraft never seemed to come to this conclusion during his short lifetime.

It is the role of the audience now, and the horror community at large, not to ignore Lovecraft’s work, not to apologize for it, but to appropriate it, as has become the tradition in the genre, in order to prove him wrong with his own work. What we imagine and what we create will fit into our contemporary progressive social criteria to various degrees, though it can’t be said that that will always be the case. The march of social progress is ceaseless and one that requires us to constantly reevaluate the morality of our literature and media. We must always be reading until we too can say all has been read. We must look into the new Necronomicons we encounter, even (perhaps especially) if they are unpleasant, because the only knowledge that can truly harm us is knowledge we ignore.