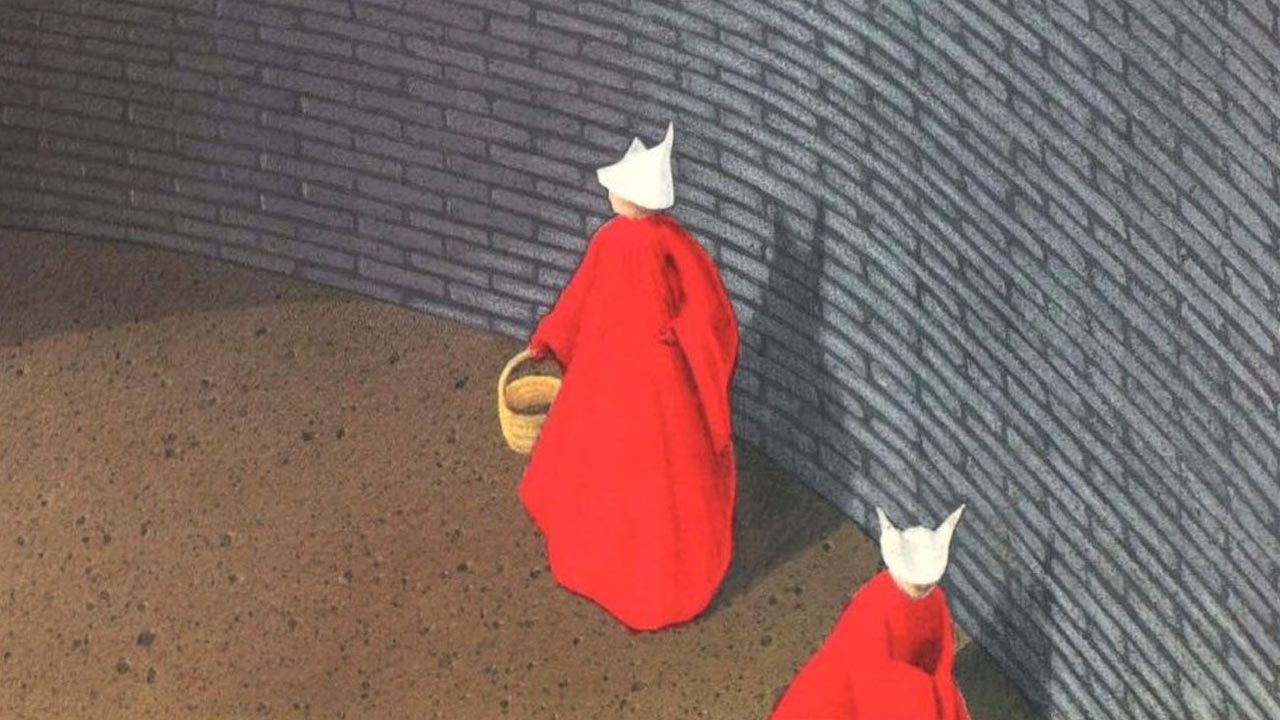

A Little Death: “The Handmaid’s Tale”

“I want to keep on living, in any form. I resign my body freely, to the uses of others. They can do what they like with me. I am abject. I feel, for the first time, their true power.”

In 1990, I read Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and watched Volker Schlondorff’s film adaptation for a German Cinema class.

At the time, I was young and naïve, and had only recently developed a tentative alliance with feminism. Unafraid to call out fellow students for the disgusting things they said about other women in my presence, I remained unsure if Take Back The Night rallies and the local collective known as C.U.N.T.S (Creative Underground Network of Truthful Sisters) were necessary.

Though I recall the film’s incredibly disturbing depiction of the monthly forced copulation between the Commander and the Handmaid (what the novel calls “The Ceremony”) my memories of both the book and the film were almost non-existent. Reading the novel again this week took me three days because I had to keep stopping to catch my breath. In this post-Trump, post-truth world, the images it conjured and the insights it presented were too prescient, too vivid, too real.

“It was after the catastrophe, when they shot the President and machine-gunned the Congress and the army declared a state of emergency. They blamed it on the Islamic fanatics, at the time. Keep calm, they said on television. Everything is under control.”

The novel is does not follow a consecutive narrative thread; the narrator/protagonist (dubbed “Offred”) provides observations on her current situation but continually interrupts herself with flashbacks. This gives it a startlingly realistic tone and makes it easy to empathize with her plight. It is the way humans function; inside our heads we are constantly navigating between the present and the past. Memories come to the forefront even as we exist in the now.

“Remembering this I remember also my mother, years before. I must have been fourteen, fifteen, that age when daughters are more embarrassed by their mothers.”

Although the dystopian, futuristic society The Handmaid’s Tale depicts is a fundamentalist Christian and patriarchal one, it becomes quickly obvious that it is a grotesque and exaggerated parody of the world as it actually existed in the US of 1985.

Atwood’s prose is filled with flower metaphors which ostensibly point to the obsession with control over fertility and the subsequent denial of sexual and bodily autonomy, but there’s something else there. The seeds of the current sociopolitical crisis were sown with Ronald Reagan and the Moral Majority’s 1980 victory, and in 2017, they have finally blossomed. It seems that Atwood’s predictions about the future have come to pass.

“We still have… he said. But he didn’t go on to say what we still had. It occurred to me that he shouldn’t be saying we, since nothing that I knew of had been taken away from him.”

The world of The Handmaid’s Tale may be fueled by misogyny, but it isn’t just the men who keep that engine running smoothly, because it is the women, in the form of The Wives, who wield the real power. A word from a disgruntled Wife and a Handmaid can be sent to the Colonies to do hard labor or even killed, strung up in the town square on the Wall with a bag over her head. The same fate befalls doctors who provide abortions or Jewish folks who refused to convert or move to Israel.

Women are encouraged to snitch on or shame each other, and for the most trivial of “offenses.” Masturbation, for example, is punished with severe beating by the Aunts who run Red Centre where women reside until they are chosen to be Handmaids. Women are even made to take the blame for awful things that were done to them, such as gang-rape.

“Bitch,” she says. “After all he did for you.”

Some might wonder why we need a television adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale now even as others think it was prompted by Trump’s election (in truth, work on the program began back in 2015). After all, there is still Schlondorff’s 1990 film, as hard to track down as it might be.

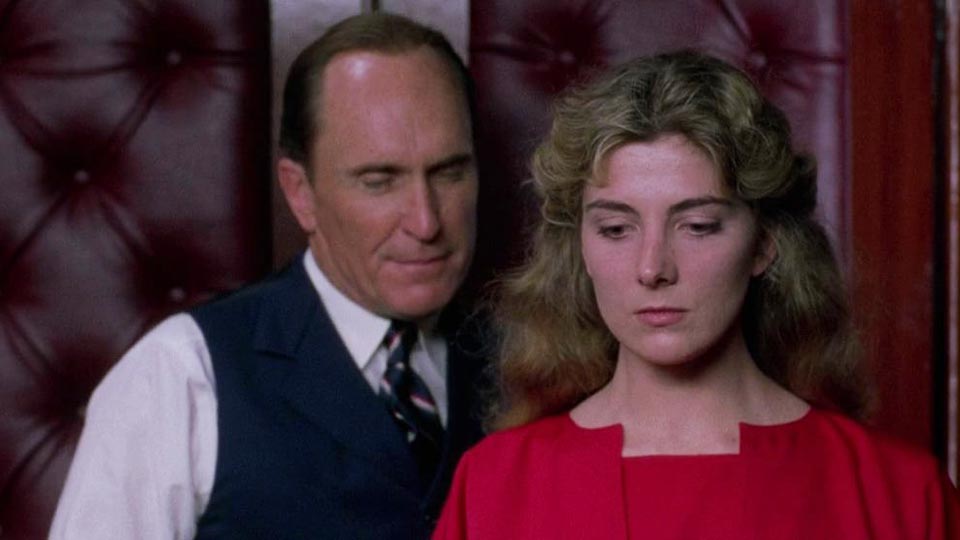

A rewatch of the film proved so disappointing, however, that I couldn’t even finish it, despite its provocative imagery. There is no attempt to show Offred’s interior world, a world so vitally important to an understanding of her character and the society in which she exists. Her best friend Moira, whom she knew before the War, becomes someone she meets at the Red Centre, thus removing all of their history together.

There is no depiction of Offred’s past life with husband Luke and how much she struggles with feeling like she has betrayed him. The movie doesn’t give any indication of how sex is verboten for everyone except Commanders and Handmaids. When Offred kisses the Commander’s chauffeur Nick in the film, it feels hasty, not the result of months of extreme, enforced chastity.

Even the dialogue feels off; in the world of the novel, Handmaids were not permitted to speak to anyone unless spoken to and then, only in the most limited terms. They were not even allowed to make eye contact with other Handmaids. Everyone is under constant surveillance. “The Eye Sees All,” the novel continually reminds us. The argument could be made that a movie could not be produced without including eye contact or dialogue, but that’s really just an excuse for a lack of creativity.

The film was justifiably panned in 1990, but a look at the difference in tone along the gender divide speaks volumes. In some cases the criticism of the film’s technical and creative failings bleeds into an outright condemnation of Atwood’s motives for writing it. Owen Gleiberman wrote in Entertainment Weekly that Atwood’s “howl of rage” was intended to push back against fundamentalism and conservatives, but sneers that “she wildly overestimates” their “influence,” and calls the book and the film “paranoid poppycock.” He even scoffs at a woman’s opinion about her own autonomy: “Is this really what our society is threatening to turn into, or is Atwood just exorcising her own fear and loathing?”

The Washington Post’s Rita Kempley wondered why the film didn’t have a woman director and notes, “If the movie stands between good old messy, toxic America and depraved Gilead, blessed be it. But alas, it's unlikely to appeal to the converted, much less bona fide brimstone eaters.”

“No mother is ever, completely, a child’s idea of what a mother should be, and I suppose it works the other way around as well. But despite everything, we didn’t do badly by one another, we did as well as most. I wish she were here, so I could tell her I finally know that.”

While the world of The Handmaid’s Tale might have seemed unreal to me in 1990, it now seems like too much to bear. Like Offred, I look back with regret on the me of 1990, wishing I’d not taken things for granted, paid more attention, been more observant, tried harder to speak out, voted more often. If ever we needed a TV adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale it would be now. Its message is both disturbingly profound and desperately important.

“That’s one of the things they do. They force you to kill, within yourself.”

Will this TV adaptation force people to finally open their eyes? Elisabeth Moss and Joseph Fiennes, two members of the cast, have been criticized for claiming that the show is “not a feminist story” but a “human” one.

However, Ann Dowd, who plays Aunt Lydia in the series, says, "I hope it has a massive effect on people. I hope they picket the White House ... I think we should never underestimate the power of morons.” Producer Warren Littlefield seems to share her sentiments: “"That's the message we want to carry out to the world. It's 'do something'.”

The Handmaid’s Tale premiered on Hulu on April 26 and will premiere on Bravo in Canada on April 30.