Letting The Right One In

And he said, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree that I commanded you not to eat from?”

The man said, “The woman you put here with me—she gave me some fruit from the tree, and I ate it.”

Then the Lord God said to the woman, “What is this you have done?”

The woman said, “The serpent deceived me, and I ate.”

--Genesis, 3:11 - 13

I was raised in a Catholic household, which included all of the things in which Catholic families participate: the Sacraments; prayers before bed; Church on Sunday; my own Rosary and Bible. For me it wasn’t just pomp and circumstance; I believed, at least until I was a teenager.

I’m not sure where the idea came from, but as a child I was profoundly afraid of becoming possessed by the Devil. Someone or something had put the idea into my mind that the Devil would seek to corrupt those who were pious so as to spit in God’s face. This filled me with a great conflict: should I somehow be less religious so as not to attract the Devil’s attention? Would that not disappoint God in some way?

I was only two years old when The Exorcist came out but I didn’t see it until I was 14, and even then it was the “edited for TV” version. The swearing and the infamous crucifix scene were naturally excised, but it was Father Karras’s dream of his mother outside of the subway station, interspersed with images of Pazuzu’s face, that scared me the most. I taped the movie off of cable TV and would freeze the bits with Pazuzu’s face and try to determine just what it was that made the face so scary. Even when I tried to watch the full uncut version of the film a few years later, it freaked me out so much that I was unable to get through it. Despite no longer being religious, old habits die hard. I no longer believed in God, but I sure as hell believed in evil, even if I didn’t think there was actually a Devil prancing around with a pitchfork.

Over the last 40 years, many films have tried to replicate the mind-numbing, gut-wrenching terror of The Exorcist with their own tales of demonic possession, but most have failed, at least for me. Once you’ve seen Regan MacNeil twist her neck around, speak with an unholy growl, vomit green fluid, and claim to be the Devil himself, nothing else can compare. This is why I was surprised when I got around to watching Penny Dreadful earlier this year.

In episode five of the show’s first season, “Closer than Sisters,” viewers find out part of what it is that makes Vanessa Ives so different and potentially dangerous. The title refers to the friendship between the staunch Catholic Vanessa and her next-door-neighbor Mina Murray. Vanessa’s religious convictions are viewed as a curiosity by the Protestant Murray family but they never come between them.

One night when she is a young teenager, Vanessa discovers her own mother having sex with Mina’s father Malcolm in the hedge maze. As a result, she begins to feel a sense of superiority: she knows something that Mina doesn’t, and this secret gives her some kind of power. A few years later, jealous of losing Mina, Vanessa seduces Captain Branson, who is supposed to wed Mina the very next day.

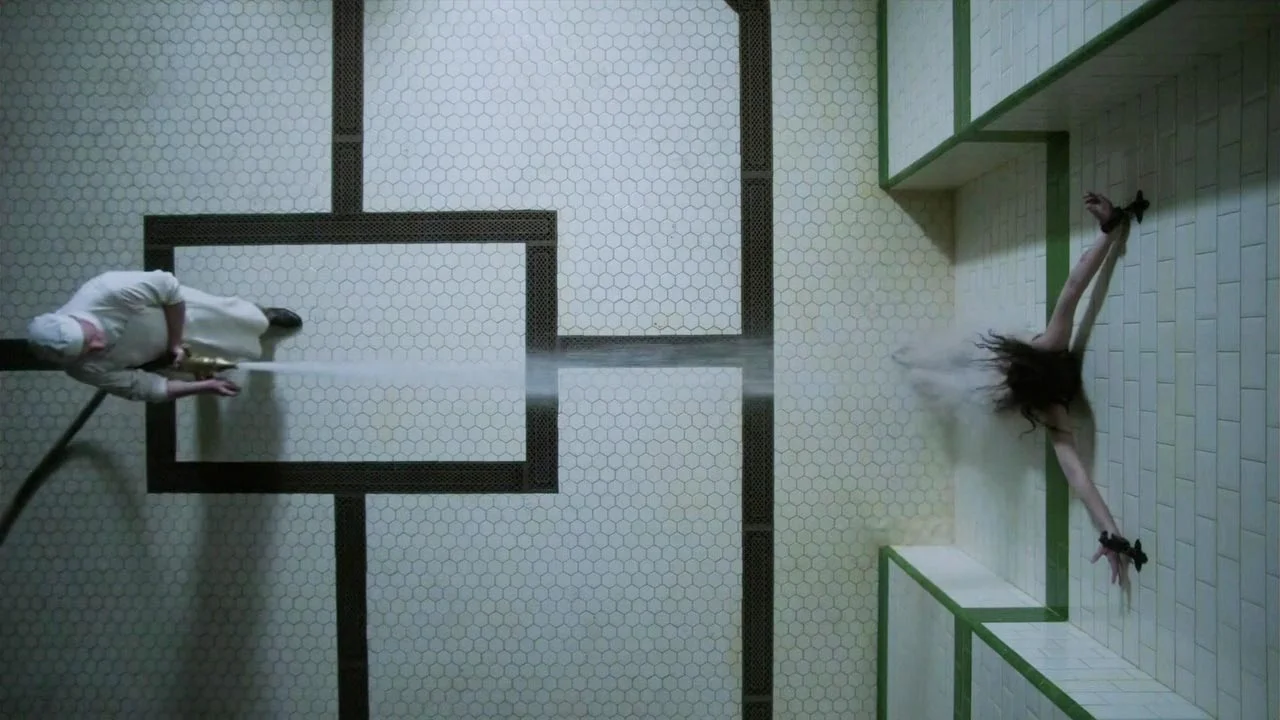

This act both opens and closes a door for and within Vanessa. The gate between the Ives and Murray estates is closed for the first time ever, but something else gains entrance into Vanessa. The identity of this entity is teased out, but scenes in which Vanessa speaks in a different voice, vomits white foam, and remains catatonic for days, all provide strong hints. After some time spent in a mental institution, enduring such torture as fire hoses, ice baths, and trepanning, Vanessa returns home, though it is unclear whether or not she is cured or just exhausted.

She isn’t alone. Malcolm Murray suddenly appears in her room one night, but Vanessa realizes it isn’t Sir Malcolm at all, but the same creature who had earlier taken possession of her soul. Not long after, alarmed by grunting noises coming from her daughter’s bedroom, Mrs. Ives goes upstairs to check on her. The image of a naked Vanessa, engaged in vigorous sex with an invisible entity is frightening enough, but it’s when Vanessa turns her eyes to her mother and we see they are completely white that the real fear takes hold. It’s certainly enough for Vanessa’s mother to drop dead immediately.

There has been no possession scene in any film or TV show that has rattled me to the core like this one. More disturbing is the idea that Vanessa herself let the evil in when she seduced her former best friend’s fiancée. This was much on my mind when I saw Robert Eggers’s The Witch a few weeks ago.

The Puritan family at the center of the film is banished from their settlement after the patriarch of the family doesn’t want to abide by the rules: essentially, he’s too pure for the Puritans. So the family ventures into the harsh wilderness, stopping short of the forest which is supposedly cursed by some form of evil.

When bad things happen—from unruly children to crops that fail and worse, an infant who vanishes without a trace—it is all blamed on the family’s teenaged daughter Thomasin, her budding breasts the physical symbol for female sexuality and thus, sin. Thomasin endures the abuse without question until she is outright accused of consorting with the Devil. Then she fights back.

There has been much discussion about the nature of the evil in The Witch, and whether or not the appearance of actual witches who reside in the woods undercuts the idea that the true evil force in the film is the kind of ignorant paranoia that spawned witch hunts in the first place, the same kind which continues to thrive today. This is complicated further by the continual appearance of a large, wild hare, which seems to beckon Thomasin into danger on various occasions. Is this rabbit a witch’s familiar, or just a friendly critter? If it’s the former, then who let the evil in? Was it Thomasin herself, mocking her irritating siblings by pretending to be a witch or standing up to her parents and calling her father out on his shortcomings?

When Thomasin finally gives in to temptation, in this case, verbally accepting the Devil into her heart and soul, she is liberated from all that has come before. This takes place in a scene that has also generated conflicting opinions. Thomasin walks naked and alone through the woods to discover a witches’ coven by a bonfire. She is literally raised up into the air and laughs with joyful abandon, perhaps for the first time ever. Does Thomasin find feminist freedom, or is she simply now beholden to another master?

Similar questions are raised by revelations in the second season of Penny Dreadful that Vanessa was born with a rare and singular gift, one that has drawn the attention of a coven of malevolent witches known as “nightcomers” who call the Devil their “master” and who appear as beautiful human women by day. Vanessa’s gifts also bind her in friendship and sisterhood to an old witch of the woods, known as the Cut-Wife of Ballentree Moor, who is wrinkled and scarred but who has refused to be seduced by the Devil. While the nightcomers enjoy the perks of being members of the landed gentry, the Cut-Wife is ostracized, spit upon, and considered a malevolent being. When the Devil’s face is lovely instead of deformed, will we even be able to recognize evil when we see it, the way I tried to do staring at Pazuzu on a grainy VHS tape?

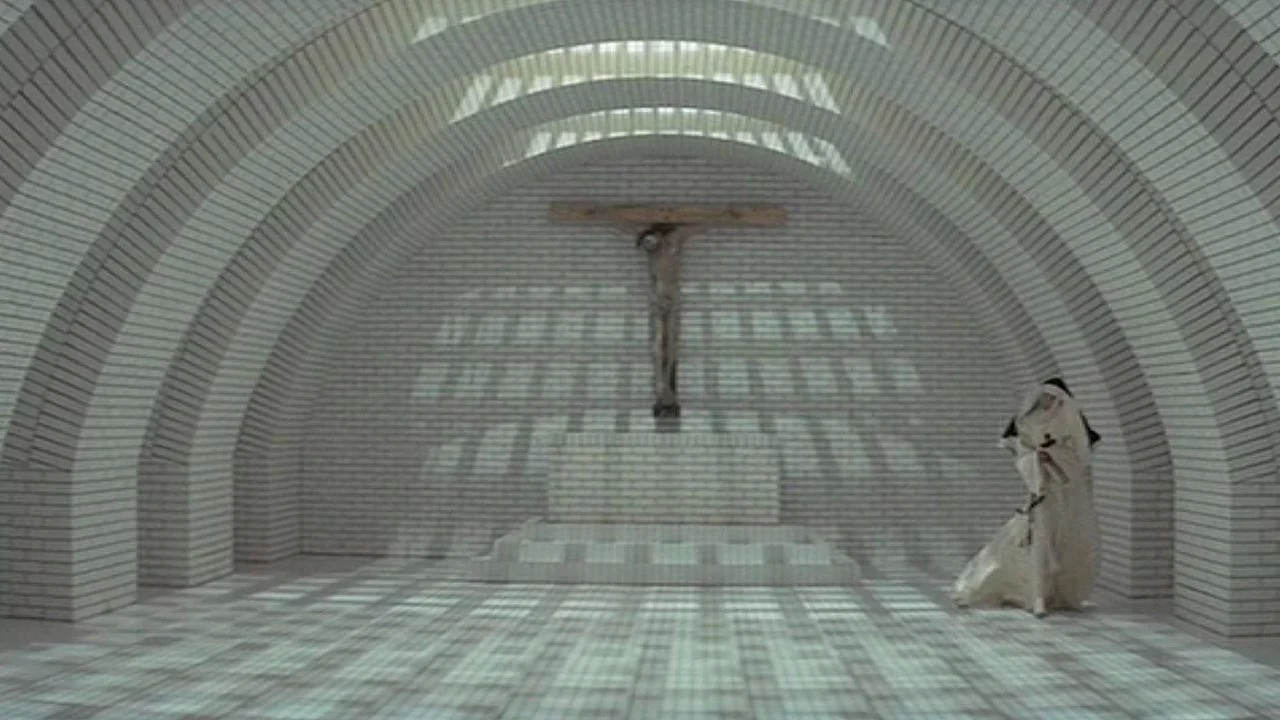

Ken Russell’s 1971 film The Devils is, like The Witch, a film set in the 17th century that addresses many of these same themes of religious hysteria and hypocrisy. While The Witch is based on contemporaneous folklore, The Devils is based on actual events. Father Urbain Grandier was tortured and executed for the crime of being in league with the Devil and using this alleged unholy power to possess a convent full of nuns.

The reality was much more mundane but just as destructive: the Bishop of Poitiers, a priest named Father Mignon; and Jeanne De Anges, the Mother Superior of the local convent of Ursuline nuns all conspired to take Grandier down because he was not only good-looking, he was also a philanderer and politically expedient in a town full of Protestants whom Cardinal Richelieu sought to convert. Mass hysteria ensued, and public “exorcisms” did take place, but the real evil was found not in Father Grandier or demons possessing nuns, but in those who would twist religion to suit their craven attempts at power.

At the end of the film version of The Devils, when the entire town of Loudun has been destroyed, the lonely figure of Father Grandier’s pious and pure-hearted wife Madeleine Grandier is seen wandering hopelessly through piles of rubble and plumes of smoke, a tragic precursor to the Final Girls that would be found throughout the rest of that decade’s horror films. Like Vanessa Ives and Thomasin, Madeleine is also victimized by evil wearing a human face, but instead of solace or sisterhood, she finds only solitude.

This is perhaps why I find it easier to have faith in the Devil than a benevolent god. There is so much horror perpetrated by humanity, there hardly needs to be a horned, cloven-hoofed creature for me to believe that collective energy of evil is far more powerful than almost anything else.