The Shoggoth Inside: Board Games And Horror

Talking With Nothing

When I was eleven I tried to speak with the devil using a piece of plastic and cardboard. It was at my cousin’s home, and she had a Ouija board. She, her brother, my brother and I were playing with the spooky toy for days, and while the experience was always oddly intimate and scary, nothing quite affected me like the ten minutes I spent alone in the hallway trying to use it by myself.

I attempted the usual ritual to open a connection to the other side, and asked the opening question: is there anyone there?

Keeping still and breathing deeply I waited for a feeling of possession to overtake me. I imagined it would be a tingling in my fingertips, or like the high pitched hum of a TV on in another room with the volume turned all the way down. I thought maybe it wouldn't necessarily have a feeling, but the cursor, made of black plastic and assembled in a foreign land, would propel itself around the board and I would have to give into its demonic motions as I tested my transcription abilities.

I did the ritual once, twice, three times and waited. I closed my eyes and breathed deeply - the way I was taught in school to pray - and then I felt it. I was suddenly aware of being completely and utterly alone. There was no ghost or devil or demon, just a little red haired mystic, staying behind at playtime to make a ghostly friend, only to have his first experience with the void.

Spooky Games

Horror and board games are perfect bedfellows. While video games offer a unique interactive, virtual experience, allowing for jumpscares and heart pounding struggles against nightmare creatures that might also be a living metaphor for male rage and murderous sexual guilt (ahem, Silent Hill 2), horror truly lives after the moment has passed. Horror is a genre of atmosphere and retrospect. In the moment of reading, viewing or playing, horror is thrilling and appalling, but when all's said and done and you’re alone in bed at night, that is when the true screaming starts.

Board games, thanks to their tactile nature, offer an extra push to the unsettling feeling you have when your home starts making those creaking sounds that might be someone - or something - unwelcome living just outside of your vision. Board games are physical objects. You interact with them and conduct a specific ritual, then put them on your shelf to sit there until next time. They aren’t framed the same way as narrative media, board games literally requiring our physical presence, movement and organic brain powered processing in order to function properly.

The most famous of the horror board games, like Ouija and the VHS tape Atmosfear series, rely on illusion to evoke the idea of a haunting. Ouija, according to heavily cited wiki-knowledge, hinges on a phenomenon called ideomotor reflex, while the VHS tape games might actually be haunted (who knows? I haven been able to fine one since 2004).

Ouija is so famous for its mislabeling of a psychological phenomenon that many people actually believe the Parker Brothers’ mystifying oracle to be some kind of MSN Messenger from beyond the grave. The power held by the printed alphabet board, especially after a good creepy session of using it, is enough to make one hide under their covers until the sun comes up, too scared to sleep in fear of the inevitable nightmares.

The misdirection of haunted board games is effective and uncanny. Ouija is a cultural touchstone, having been adopted by the horror genre in much the same way as Lovecraft’s fictional book within a book, The Necronomicon. Ouija, a board game you can buy for ten dollars at a Toys"R"Us, is an icon of the occult. And yet, for all its cultural importance, Ouija is not the most horrific board game on my shelf (well, technically on my wall, since mine is prominently on display as a morbid conversation piece). While Ouija evokes a sense of sublime, almost campy Halloween-ishness, the game that makes me feel most small and human and absurd to a point of losing sleep is Arkham Horror.

A Game Against Nothing

We made the decision to play Arkham Horror, my partner Emma and I, under the pitch black sky of an impending summer thunderstorm. It was one of those eerie tempests, bringing night a full two hours before the sun should actually set, and never actually raining. I grew up knowing this as Tornado weather, but now I see it as the birth of a new age in my life: one in which I understand what it takes to fight against nothing.

Emma and I arrived home to my Toronto apartment under dry crashes of thunder and began to set up the game we’d just purchased on a whim. Six hours later, we gave up.

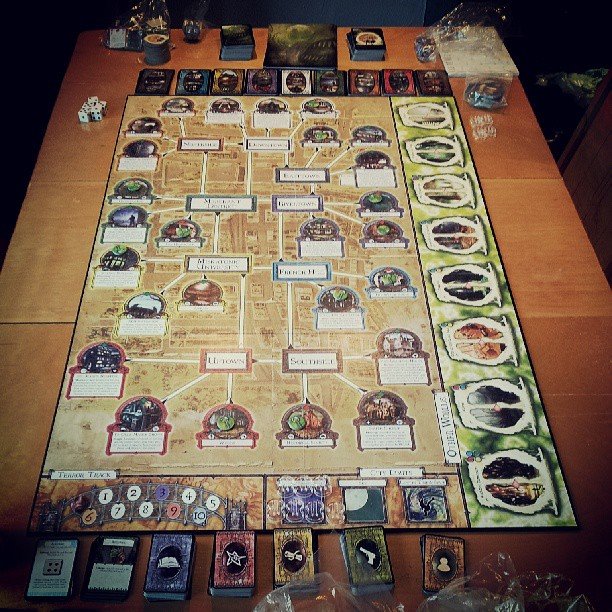

Arkham Horror is massive. Designed to be played with as many as eight players and as few as one, it is a cooperative (or solo) experience set in the sci-fi 1920s of H.P. Lovecraft inspired fiction. Players take on the role of investigators, each with their own special abilities, and attempt to prevent an ancient extraterrestrial god from awakening and bringing about one of many possible apocalypses. There are about 600 pieces involved and the average game is said to take between six to twelve hours of play.

That first night, under the angry sky, Emma and I were defeated personally, not by virtue of the game’s pure difficulty, but because its learning curve is steeper than a R’lyehan sidewalk (at once a steep incline and also reminiscent of bitter flavours as its patterns draw one down into an eternal spiral). We went to bed and slept the unblinking sleep of those defeated by a board game played by no one.

Now, years later, Emma and I can beat Arkham Horror in an average of four hours time. Thanks to our perseverance, we know it inside out, and even though we don’t always win, we can understand what we’re doing, and that is a victory in and of itself.

The extreme difficulty and Lovecraftian setting are, in their own ways, horrific. There is a certain nervous feeling in the pit of my stomach every time I see the final piece added to the game board before playing. But the true terror of Arkham Horror lies in its mechanical nature.

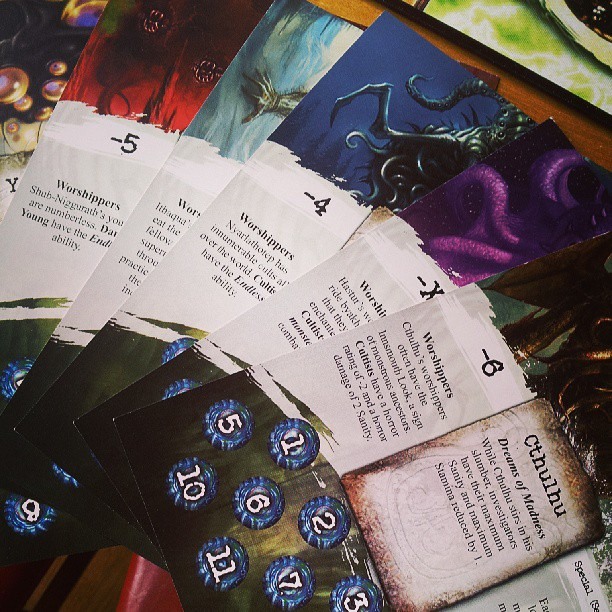

As a cooperative game, Arkham Horror relies heavily on several decks of cards to automate the eldritch force that the players combat. As a player enters a new area in Arkham, or one of the game’s many extra-dimensional worlds, she draws a card. The card details a narrative event and describes how this affects the player. At the conclusion of a round of play, the board gets a turn: another card is drawn and the instructions printed on it are followed to the letter. In all of these cases it is very rare that anything good will happen to any of the human participants. The game’s obscure rules serve as a barrier to entry, but the real deterrent to playing Arkham Horror is its sadistic difficulty.

The thing is, though, Arkham Horror isn’t really sadistic as much as it is masochistic. The board feels like my enemy every time I roll the dice and try to burn a demonic goat with my character’s molotov cocktail, but I am the one reading the cards; it’s me that’s removing heart counters in accordance with their weird instructions. When the game is lost, as it often is, the temptation is to blame the rules or luck, but really it’s me. I chose to do what it said, following the unholy instructions as if under the influence of that strange ideomotor response that let my cousins talk to the devil when I was eleven, but failed me in private.

The terror of an imagination is that it conjures what it wants, and as you can see with Ouija, that’s not something we are always able to control. Arkham Horror is the epitome of this other inside of us, summoning a being out of nothing against which we play a game.

The Room

I learned to play Arkham Horror like many people do, by watching an eleven part YouTube series of a man explaining the rules in a motel room. Having set everything up on the room’s furniture, the faceless uploader walks his audience through the motions of a byzantine ritual, revealing the occulted information that enabled me and countless others to bring their board games to life.

The videos themselves are amazingly appropriate for such an occulted pastime. The actual footage offers no explanation as to why the teacher is alone in the room, or why he chose to bring a massive board game with him, and it evokes the strange obsession that brought you to his channel in the first place. Arkham Horror makes you thirsty for its secrets.

While the videos are incredibly useful in learning to use the contents of the infernal box, they also serve as an example of the game’s semi-sentience. The reason a lonely man in a hotel room can teach strangers to play Arkham Horror is because it can be played alone, like an evil twelve hour game of solitaire.

Alone in a room, by following the secret rituals taught to you by a faceless man in a motel, you can summon a malevolent presence to devour your time. You can go through the motions, rolling dice and reading text, moving pieces in obscure patterns on a map of a non existent city. You count and do abstract math. You spend your hours alone, in the presence of a self-made monster, turning nothing into something tangible. You give in to your deeply human need to never be alone and without purpose, even if it means creating something truly awful.